Music has forever been an important part of the Nepali culture. From the day a baby takes his first breath to the moment he breathes his last, music will be around him. Its presence is undeniable through the various courses in his life, in marriage and festivities, in life and in death.

However, music is also no longer what it used to be in the old days. With waves of modern culture surging in and changes in lifestyle, Nepali music has wholeheartedly embraced the strings of guitar, keys of pianos and beats of the drums. All the while, the stringed instruments of Nepal – the sitar, the old keys of harmoniums and the damahas – sit forlorn and quiet, slowly gathering dust.

This is not to say that there have been no musicians doing their part in keeping these instruments alive. There have been quite a few of them and here we talk to two such artists.

Traditionally folk

Kiran Nepali is no stranger to the Nepali Music scene. As a member of Kutumba, a band most notable for their traditional sounds, he has been heralded as the one who has made great contributions in reviving the traditional sounds that were getting lost with time.

Kiran Nepali is no stranger to the Nepali Music scene. As a member of Kutumba, a band most notable for their traditional sounds, he has been heralded as the one who has made great contributions in reviving the traditional sounds that were getting lost with time.

My journey back to Nepal

Sarangi has always belonged to the Gandharva family of the Nepali caste hierarchy. In the olden days, they took to sitting under the shades of trees and sang narrative tales and folk songs for travelers. Sarangi, thus, has always been a major part of the Nepali culture.

Kiran Nepali belonged to one such family of Gandharvas. Growing up, the sound was all around him – generations in his family had played the instrument and it was naturally assumed that he would too. However, as a kid, he took to playing the guitar and did so for quite a while.

When he was 22 years old though, he wondered what it would be like to play the sarangi and he didn’t need to look far for someone to help with the learning process. His own father was a skilled sarangi player himself. With time, he eventually built love for the instrument. “I loved how original sarangi sounded. It had a very typical Nepali feel to it, one that opened a whole perspective about Nepali folk culture and life at its simplest,” he says. Sarangi is the only instrument closest to the human voice and this, he says, is exactly why he feels a special connection with it.

This newly cultured love led him to playing the instrument to perfection in lesser time than expected. He began staging his performances and it was only in the year 2008, with a collaboration project with Kutumba for a program ‘Change’, that he was included in the original lineup.

Since then he has played with Bipul Chhetri and the Traveling Band, Kutumba and launched ‘Project Sarangi’, a project specifically for the youths and aimed at reviving the waning culture of playing sarangi.

Nepali is also one of the proprietors of electric sarangi. This, he explains, came off from having troubles in conveying the sound of sarangi during live shows. “Originally we used microphones to amplify the sound, but it tempered with the original sound so we were forced to look for alternatives,” he explains. As a guitarist himself, he wondered if he could incorporate the electric nature of the guitar into the sarangi too. He researched on this and worked with instrument makers to customize an electric sarangi that is, arguably, the first of its kind.

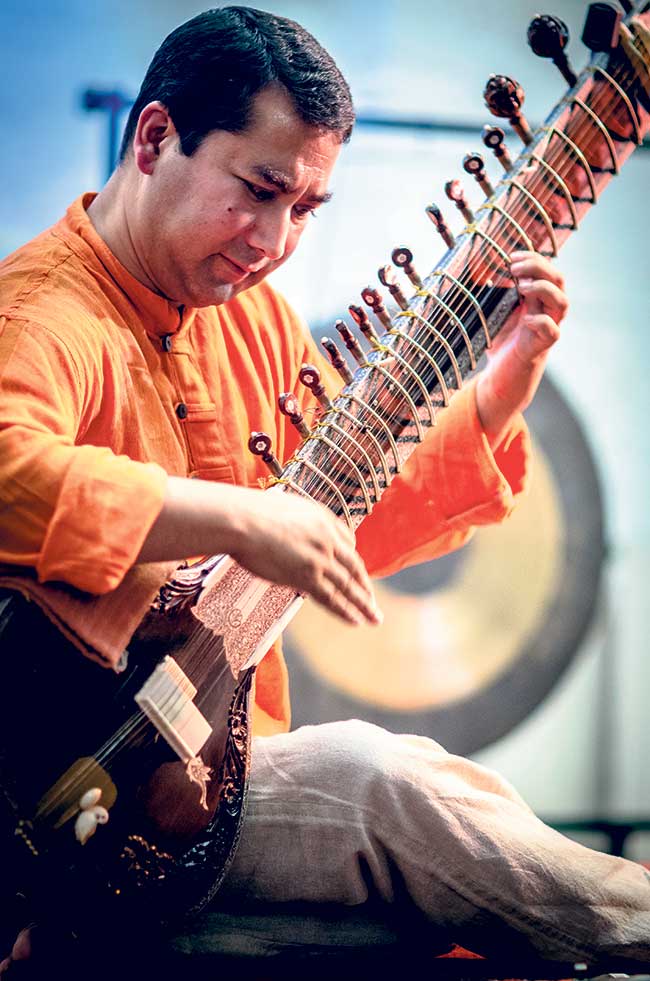

The classic sitar

If Pandit Ravi Shankar has his daughter protégé, Anoushka Shankar honoring his legacy then Tara Bir Singh Tuladhar, also called the Nepali Ravi Shankar, has his son, Satendra Bir Tuladhar, doing the same.

If Pandit Ravi Shankar has his daughter protégé, Anoushka Shankar honoring his legacy then Tara Bir Singh Tuladhar, also called the Nepali Ravi Shankar, has his son, Satendra Bir Tuladhar, doing the same.

No other Nepali musician, Satendra claims, has toured as prolifically as his father has. In his formative years, he had scant interest in the instrument but with frequent visits from students seeking to learn from his father he found himself imitating them. Learning sitar for him was less a matter of interest so much as it was about the environment he grew up in.

His father was a first generation player but it carried on to his children. Each of his four children, including Satendra, holds a Masters degree in sitar. Satendra took to playing sitar professionally and has, since then, proved to be quite the successor to his father’s artistry and legacy.

Since 1994, Satendra has extensively toured major cities in Europe, India and Thailand. With his own compositions he has performed before masses to great accolades and is booked every year to perform at venues in Europe. He calls sitar an integral part of his being, an instrument without which his identity is incomplete. Music, for him, has always been synonymous to meditation and transference of energy. He calls musicians great music quantifiers who share their energy through the melodies they produce. Sitar is how he attunes himself to everything that lives therein.

Despite being a touring sitarist, he also takes in students to teach them the basics and introduce them to the world of classical music. However his students, he says, mostly comprise of people of other nationalities. There are only a few Nepali children with ages that median around 11 years. This, he says is something that warms his heart, seeing as how Nepali parents these days are allowing their children the liberation to pursue the things they want to. “Most children signed up for classes not because their parents forced them to, but because they themselves wanted to,” he concludes.