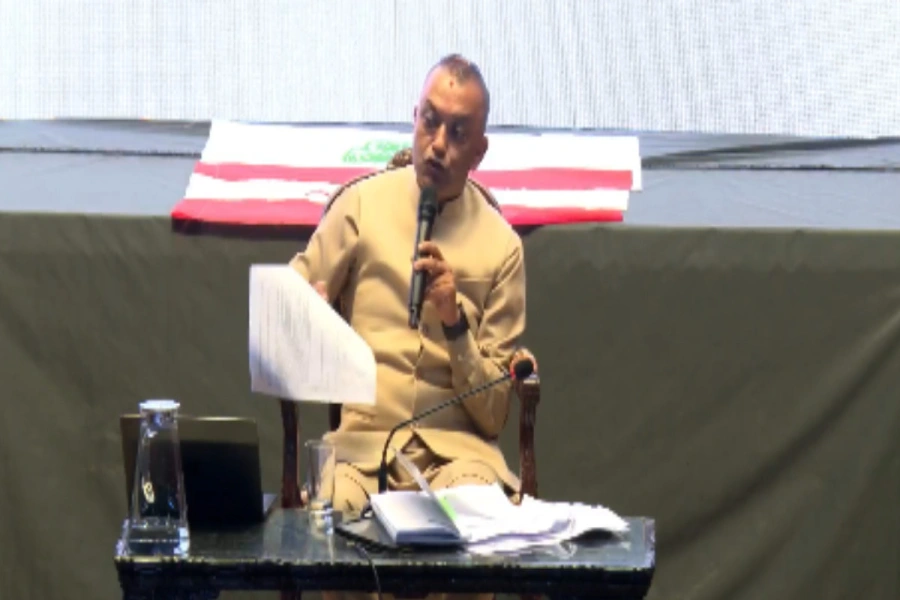

Finlit Nepal’s Prakash Koirala has recently returned with much accolade from an award ceremony hosted by the London Institute of Banking and Finance in England’s capital. His organization had been nominated for its work in promoting financial integration alongside big guns like the HSBC Bank and Lloyds Bank. What’s more, Finlit Nepal won that category.

Currently back in Kathmandu, Koirala is sitting in meetings with the likes of Nepal-Bangladesh Bank to initiate programs and curriculums that they are already carrying out with financial institutions like Rastriya Bank and Nabil Bank, just to name a few.

“We are steadily moving ahead with our projects,” he says. Thus the name of Finlit Nepal and its credibility is increasing these days however, Koirala reveals that he has been working on his ideas for nearly a decade now.

The 26-year-old talks about how it all started with a chance meeting with a local boy in his hometown of Dolakha. This was way back in 2009 but Koirala still remembers it because it had struck a strong chord. He recalls that the boy was incredibly stressed about the difficulties of keeping up in school and also, about his uncertain future.

“Apparently his parents were fighting. His father was abusive and he was clearly disturbed by it,” explains Koirala, “and all of this could be traced back to his family’s financial problems.”

Personally, Koirala shares that he was raised to always be financially responsible. He credits his grandfather for the guidance. He had grown up being regularly briefed on how to spend as well as maintain financial discipline so lack of such necessary knowledge in his own community, he says, had bothered him even then.

Monkey rampage a menace to heritage- Study

So Finlit Nepal’s grand plan of encouraging financial literacy and initiating financial integration on a national level started rather humbly. Starting from 2009 to 2015, Koirala volunteered to initiate programs on the matter all on his own.

In fact, for his very first community initiative back in 2009, he shares that he had to hitch a ride with a travelling group from the Art of Living club.

“I had no money of my own to carry out programs. So I offered to volunteer for Art of Living, if they allowed me to accompany them in their village trips. They agreed and my first trip was to a remote village in Bajhang. I stayed there for a month. I helped them out with their programs but, on the side, I also carried out my initiative,” he says.

His first self-designed outreach program covered the basic aspects of saving, loan, investment, and insurance. His target groups were students from classes seven and above, the women of the community, and the respective ‘samuha’ local groups engaged in various sectors for development. “Even the simplest finance management facts proved to be a revelation for them,” he says.

On that very first program in Bajhang, he taught participants about bad spending habits and the need as well as ways to control them. He decided to convince them by helping them differentiate between their needs and their wants.

“For instance, is it necessary to eat meat every day? In our villages, many are unaware about the very concept of need and want,” explains Koirala, “When they realized the difference, I encouraged them to prioritize and keep track of their expenses.”

He found that simple things like explaining the benefits of being wary about your daily expenses, even the slightest increment from say Rs 45 today to Rs 55 the next day was helpful for the villagers. Giving them a platform to consider and compare their expense priorities, their capacity, their responsibility alongside other members of the community turned out to be a real eye opener.

At the end of the month, Koirala reports that the groups as well as the students had saved somewhere around Rs 3000. The fathers were cutting down on their alcohol intake and even the principal of the school was talking about how students had stopped wasting money on buying snacks. It was all practical advice designed to help them understand their own finances.

The positive result encouraged Koirala to not only travel and reach out to other villages around the country but also to approach institutions like banks and micro finance companies that were helping out the public with their finances.

“I was successful enough to encourage people to save but in the villages people are intimidated by banks so they choose not to use them. Similarly, when you are on the field, you witness how products and deals designed by micro finance companies don’t suit their targeted clients,” says Koirala, stressing on the need for these institutions to come up with integrative schemes.

Koirala is one who believes theoretical knowledge alone doesn’t cut it. As a simple example, he shares a survey they had carried out at Bhat Bhateni’s new branch launch in Thimi during the Dashain festivals. Majority of the people they had talked to carried debit cards but they didn’t use them. When asked if they knew using debit cards gave them 10 percent back, they claimed to be unaware about it. Later, they even thanked him for giving the information.

These real experiences prove the urgency for financial literacy and not just in the villages. It is equally important in our cities as well and among all age groups, stresses Koirala.

He mentions another incident when, at a program in Rato Bangla School, he had asked the students where money came from. Shockingly, the answer he got was an ATM. So, with Finlit Nepal, he has been helping make curriculums and carrying out programs for banks and micro finance companies to make their services more integrative.

“Don’t just give them the definition of saving and banking,” he says, “give them useful tips. Don’t just talk about loan offers, provide handy information about loan utilization, installment calculation and so on. We cannot afford to assume that people already know these things because evidence shows otherwise.”

Finlit has even invested in assessments to see the kind of changes their programs have yielded across the 43 districts that they have reached so far. But they also claim that this is only the beginning, they have bigger ideas and plans to improve financial literacy and integration in the future.