Internal problems—technical and political—abound. On the technical side, the redistricting of constituencies consistent with the 2011 census is yet to be set in motion, and there will be many disagreements in the process. Many political parties are yet to be registered. Voting machines are yet to be procured. Security and transport provisions are yet to be worked out. With tenacious efforts, these technical bumps could be smoothed out.

However, political problems would be more difficult to tackle.

For instance, despite its sound and fury, the UCPN (Maoist) does not want the elections on schedule. Whenever it wants to procrastinate, it abandons its accord with other parties. This time, it has abandoned the agreement, among others, on decreasing the number of CA II members to 491 from 601. Last time, it did that on the number and nature of states at the last minute to prevent the CA I from completing its task.

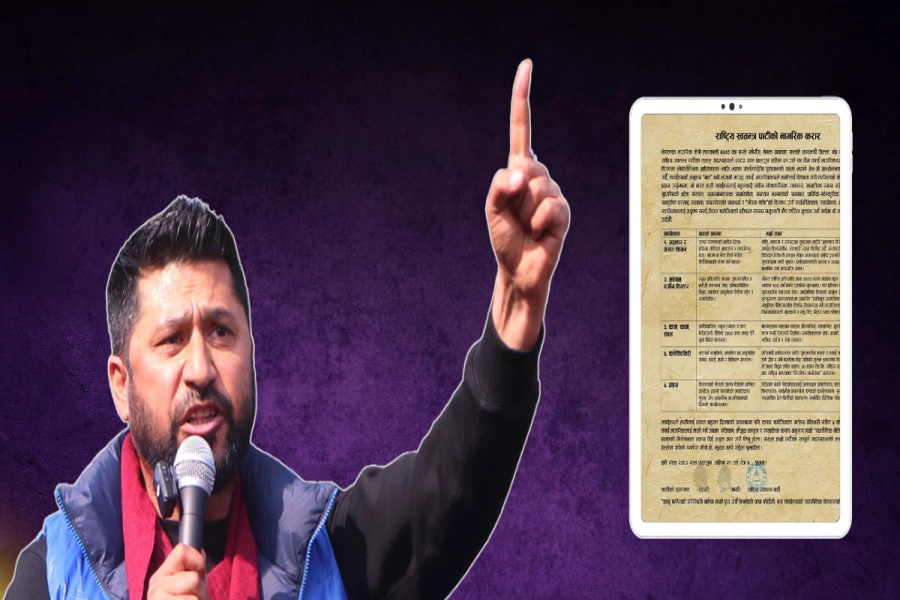

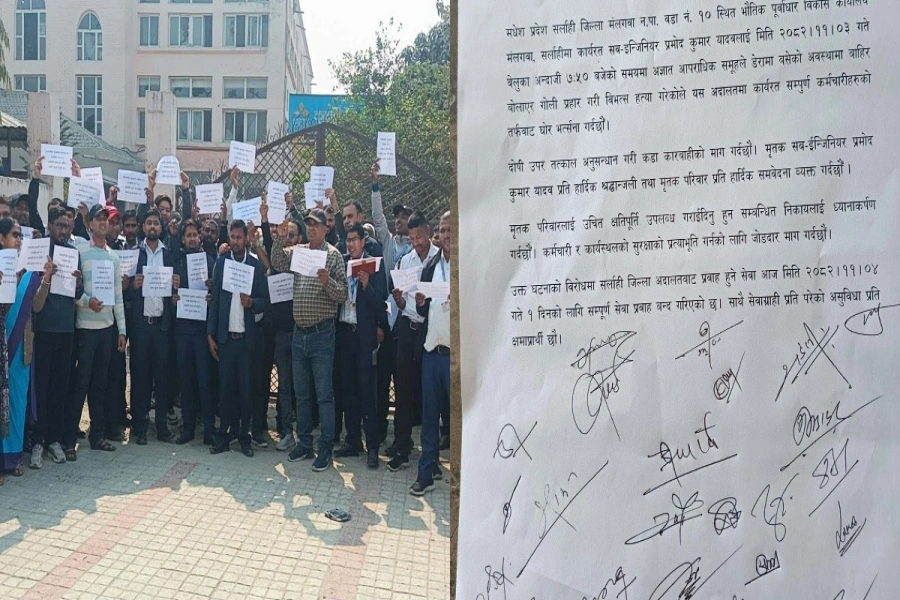

Besides, 33 political parties, led by the CPN-Maoist, have hit the streets. Of late, the CPN-Maoist has asked for postponing the elections and safeguarding national interest mainly by annulling the citizenship certificates given recently to non-citizens. These demands are more conciliatory than the previous ones asking for the ouster of the Regmi government and a pro-people (read: communist) constitution drafted through political consensus. Among other agitating parties, Upendra Yadav’s MJF wants citizenship certificates issued to all remaining Madheshis before the vote. The rest have their own demands.

While the CPN-Maoist’s new demands are easier to fulfill than the old ones, the MJF’s are impossible to meet before the vote. However, such demands are the Potemkin’s village. The real goal of the protesting parties is to have a share in power, pelf and privilege before going to the polls. It is understandable.

When the undivided UCPN (Maoist) was in government, the Pushpakamal-Baburam faction, also known now as the cash-Maoists, denied the Baidya faction a fair share of ministerial berths. It locked the Baidya faction out of the vault of the wealth accumulated during and after the insurgency. The incensed Baidya faction split and formed the CPN-Maoist, known as dash-Maoist. After the separation, the cash-Maoists shelled out some assets, but far from a fair share. To add insult to injury, they finagled the Nepali Congress, CPN-UML, and Madheshi Front to shut the dash-Maoists out of the High Level Political Committee, the puppeteer that moves the puppet Regmi government.

The dash-Maoists want from protests what they failed to get from the mother party in bargain. So they have kept the door open for reintegration with the mother party by not separately registering with the Election Commission. They have vowed to disrupt the polls if their public demands are not met. Some leaders from the Big Four, like Bamdev Gautam, have entertained the idea of having the vote without the dash-Maoists and Upendra Yadav’s MJF. But that is unrealistic. The dash-Maoists have the capacity to pummel the polls into a paste using the disgruntled members of the notorious Young Communist League and former combatants in their fold.

Goddess Laxmi makes the enmity arising from money so vicious that the rivals can never forget or forgive. If the old generation passes away, the new carries it on as a family feud. Only in films can you see the hero and heroin from rival families falling in love and bringing them together after much suffering. In real life, it happens only if money changes hand to mutual satisfaction. It is yet to happen between the cash- and dash-Maoists.

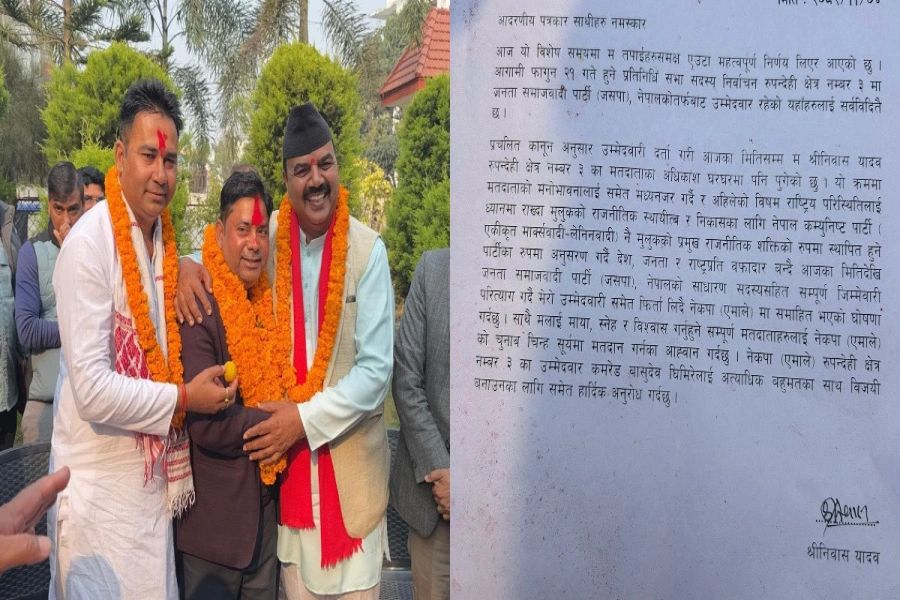

Upendra Yadav has made the popular and perennial demand for citizenship a bargaining chip for a piece of power, money and privilege as well. He needs these vital resources to garner support from the disenchanted voters and revive his moribund party, which has eroded into a miniscule of its former self. Most other small parties too want time and resources to find their feet.

So the election on November 19 is highly uncertain, if not impossible.

Even if the polls were held, the CA II may die in court. The Interim Constitution was amended through an ordinance to make room for the Regmi government and the polls. Several court cases are challenging the constitutionality of this measure. On strict legal grounds, an ordinance is the constitution’s baby. The baby cannot beget its parent. So a bench of independently-minded Supreme Court justices could rule the Regmi administration and CA II polls unconstitutional. Courts have voided parliamentary elections in Egypt and Kuwait on such grounds.

Even if the CA II survives these formidable vicissitudes, it might not be able to put together the law of the land. Many differences faced by the CA I remain unresolved. For instance, the debate over whether the form of government should be presidential, parliamentary or mixed is likely to be reopened. The independence of judiciary will be another serious bone of contention. Emotions over the number and nature of federal states are as raw as ever. These issues will determine who yields power and how, and the parties will stick to their guns.

The raw emotions have been fueled and stoked further by external players. Western countries support ethnic federalism that may give their NGOs more freedom to proselytize the minorities through bribe, deception and coercion; this might eventually break Nepal, just like Sudan and Indonesia. China and India have their conflicting strategic interests to safeguard and promote in Nepal.

China does not want on its borders economically and politically weak and socially fractious ethnic states, which might be soft to secessionist elements from Tibet and Dharmashala, due to shared culture. It also fears that just one or two state(s) in the Tarai, on the Indian border, would be capable of exerting pressure on Kathmandu to tilt towards its southern neighbor further and upset the strategic balance in Nepal.

Nepal has been operating under Indian security umbrella created by the 1950 treaty and 1965 letter of exchange. India wants to maintain and strengthen it. For instance, it imposed the economic impasse of 1989/90 to punish Nepal for importing Chinese weapons without its approval to maintain the umbrella. Now India is trying, as China fears, to strengthen the umbrella by creating just one or two state(s) in the Tarai and using their abidingly pro-Indian elite to make Nepal as pliant as Bhutan. The Indian diplomat SD Mehta’s call on Madheshi leaders to unleash a storm for “One Madhesh, One Pradesh” was part of this strategy.

So is the exceptionally warm treatment accorded to Pushpa Kamal Dahal, a communist, and Sher Bahadur Deuba, a pro-Washington Nepali Congress leader, during their recent visit to India. India perceives these leaders, based on their track record, as more willing and ready than their rivals and competitors to make a Faustian bargain for power and support “One Madhesh, One Pradesh.”

Dahal has proved the Indian perception right by proposing a single autonomous Madhesh, which has delighted India and horrified China and a large section of Nepali people. Time will tell whether Dueba follows suit.

It is therefore that writing a new constitution is very difficult.

If Nepali leaders want the vote to take place on November 19 and the CA II to write a new constitution, they must begin to resolve technical and political problems quickly. Otherwise, Nepal may have to import a constitution, just like everything else, from outside.

Happy Constitution Day!