We look forward to the day when our women have the courage to expose the Weinsteins among us

When the social media in the West is inundated with women’s experience of harassment and their harrowing stories of its impact on their psychological and physical health, I could not but wonder, what would have been the experience of women in my society where rape often goes unnoticed and considered women’s fault; where girls are commodity—people literally trade them to brothels; where killing girls-fetuses is the norm; where women are set on fire for the lack of dowry; where the social infrastructure is designed such that any conversation on sex or sex-related topic is a taboo; and where there is no mechanism to hear the women’s voice, where women are the culprits no matter what.

When the Western world described #metoo as the biggest watershed moment for the feminist movement—a real awakening of the women power—I started thinking about its implication in my own community where women are literally second class citizens. The recent avalanche of the ‘metoo’ experience reflected the pervasiveness of harassment women go through in the developed society where women are independent, educated and relatively powerful.

It is not my fault!

What about my society where women are powerless diminutive creatures? Many women in the West who have shared their harassment stories are saying that speaking up has given them a sense of catharsis that they needed for closure. Will there be a time when our women will be confident enough to come forward with their personal stories and experience that sense of liberation as western women feel now?

Bold and bad

In Nepal, workplace sexual harassment law is fairly new. The Sexual Harassment at Workplace Prevention Act came into effect only in 2015. Before that, the Muluki Ain’s section ‘Acts of Sexual Intent’ covered all sexual offences, with up to a year in punishment and fine up to Rs 10,000. Whatever is written in the law-book, implementation, or even complains on harassments are scant, mainly because of the society’s stigma and hush-hush attitude to sexual crimes.

Women are expected to “avoid the situations”, remain in “their boundaries” and be “good” to prevent any sort of harassment. When I was growing up in my village, no girls would cross the road in-front of the boy’s hostel or the boy’s playing-ground, and we absolutely could not go anywhere after six. Girls who wore short skirts were the bad ones (“uttauli”) and extroverts were worse (“chothale”, “pothi basyo”, “badta janne”). There are so many negative-derogatory-horrifying adjectives for girls, it is astounding.

Back in those days, in the circle of my mom-aunts-fufus, they had these hush-hush conversations and the informal guff-gaff where they used to tell stories that I didn’t understand at that time. The language was always indirect. They used to say something like phalanaa le phalaana lai samaatyo (“this person caught that person”) or phalaana le phalaana lai chopyo (“this person covered that person”). It could have been anything—from rape to groping to hassling to touching to catcalling, anything! And except for the legal and bookish words that no one even pronounces, there is no colloquial word for sexual harassment in Nepali language.

The society has desensitized the harassment issues to the extent that everybody is expected to accept it as the norm. If we do a survey in the whole of Nepal-India-Pakistan-Bangladesh region, I am sure each and every woman, from every generation, has been through some kind of sexual harassment. But no one talks about it!

Marginalized voices

It is even worse for the marginalized women. For example, the plight of the dalit women is the worst. They are ostracized, blamed as witches, boksi or temptress. Nobody in their right mind would believe that a poverty-stricken, ragged woman with no latches on her hut and socially no power would have a consensual affair with powerful men. The irony is that a bahun-priest who at other times would not even walk the way where dalits have walked would be completely comfortable thrusting his penis inside the so called “untouchables”. And yet they are revered as priests, as head-masters, as real-estate moguls, leaders—while women are burnt as witches.

Many would argue that after the Maoist revolution, women have become quite outspoken. I had a combatant friend who used to tell me that the weapon in hand made her feel real powerful and confident. But I wonder, in those camps, were they safe? Did nobody grope/fondle/touch/ or rape them? We did not talk about it. We would not know because nobody tells. The silence is the way of life, which is understandable. The consequence of spoken word is so high. Victims have to go through numerous legal and social backlashes that it is far easier to be silent.

However, whatever the situation until now, surely, we all hope for a society that is safe for everyone; a society where women’s words are taken seriously and the consequence of spoken words befall on real perpetrators rather than victims themselves. We all look forward to the day when women in our community have courage to speak up, and when our words would expose the Weinsteins of our community.

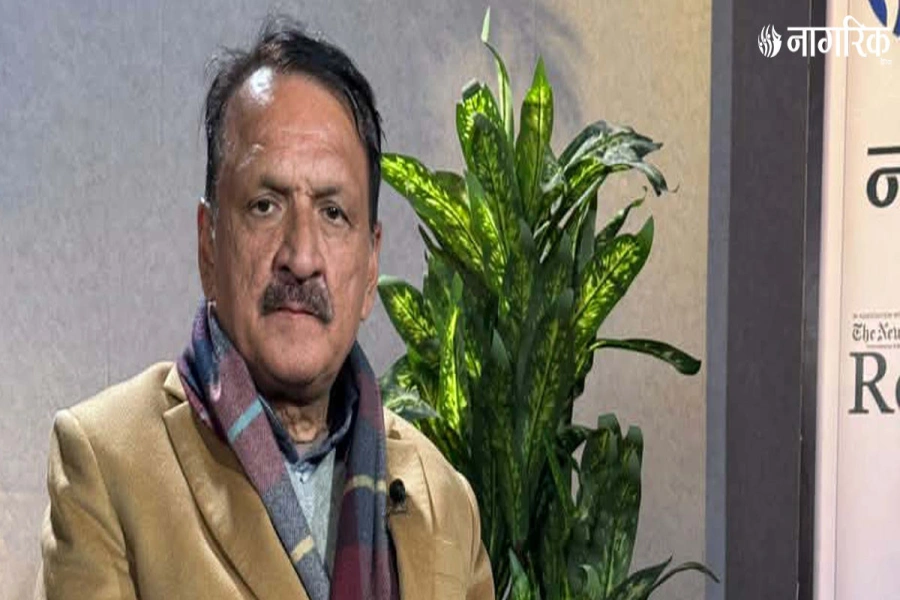

The author is a mother. She is deeply passionate about women’s rights and empowerment