BP Koirala was an institution in himself. The undisputed leader of Nepali Congress for nearly 30 years, it was under Koirala that the party adopted democratic socialism as its guiding principle. On the international stage, too, Koirala, during his 18 months as prime minister, exuded quiet confidence of a leader who was sure of his (socialist) moorings. Part of the reason King Mahendra decided to overthrow Koirala's democratic government, it's said, was because Mahendra was jealous of the upstart from Congress getting the international limelight that his genius alone deserved.It would have been interesting to witness the evolution of BP Koirala-the-statesman without the screeching breaks of King Mahendra's 1960 coup. But whether you are a democrat or a dictator, your options as the ruler of Nepal are limited. King Prithvi Narayan Shah's advice to finely balance India and China for the country's long-term viability holds as true in the post-blockade, 21st-century Nepal as it did in the post-unification Nepal of the 18th century. You cannot change geopolitics.

But you can manage it. As Andrew Bingham Kennedy argues in his fascinating book, The International Ambitions of Mao and Nehru, the actions of individual actors matter. The contemporary histories of China and India are shaped to a large extent by Mao and Nehru respectively. The two men towered above everyone else in their respective countries. The military-minded Mao made continuous warfare against foreign enemies the defining feature of his reign. On the other extreme was Nehru, whose faith in diplomacy was as unshakable, and who would only most reluctantly agree to a military option to settle an international dispute. The stamps of these two men are evident in the foreign policy priorities of China and India to this day.

Old haunt

So, yes, having BP at the head of the government, say, for around a decade could have resulted in vastly different foreign policy priorities for Nepal—the first democratically elected prime minister of Nepal leaving as lasting an impression on the international stage for Nepal as Mao and Nehru did in case of China and India. We will never know. But as the party BP helped found in 1947 heads into its 13th General Convention (March 3-6), the party's stated foreign policy priorities—but without a BP-like persuasive figure to articulate them—are worth exploring.

The country, according to Nepali Congress election manifesto for the 2013 second Constituent Assembly elections, should continue to have "the United Nations Charter, panchsheel, non-alignment, national interest and security, and world peace" as the central planks of its foreign policy. Nepal's relations with India and China, as per the election manifesto, will be based on "practicality" and "objectivity" and guided by the principles of equality, sovereignty, territorial integrity and international norms. The manifesto also promises 'creative transformation' of the SAARC organization, renewed focus on economic diplomacy and gradual reduction of the country's dependence on foreign aid.

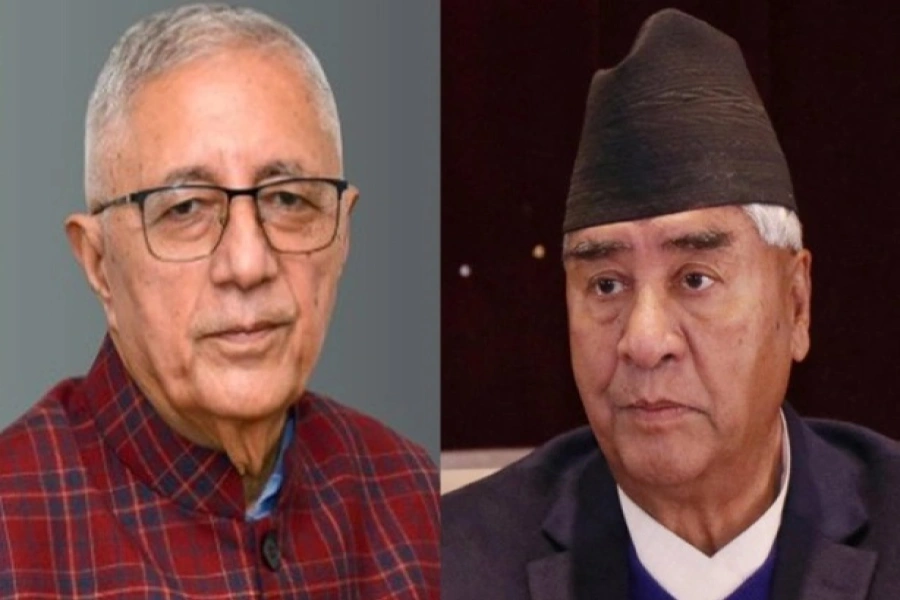

On the balance of things, Congress has all important aspects of Nepal's foreign policy nailed down. But the problem is that at the party's most important forum, the general convention, none of these important foreign policy issues are likely to be discussed. By the looks of things whatever discussions there are will be limited to who gets what. With Ram Chandra Poudel and Sher Bahadur Deuba as the two frontrunners for party president, perhaps it is too much to hope for a meaningful foreign policy outlook to emerge from the four-day jamboree in Kathmandu.

One thing that should be discussed (but most certainly won't) is Nepal's relations with India post-blockade. How does Congress propose to resolve the central paradox in Nepali foreign policy today: how do we modify our ties with a bullying India with which we cannot afford to have bad relations? Nor, on a side note, is it likely that any of the 3,000-odd delegates at the general convention would question their leaders' part in the hollowing out of Nepali diplomacy, with, among other things, their choice of no-good party apparatchiks as important ambassadors.

Conventional wisdom

Having such policy-related discussions is also in the party's interest. Perhaps Congress does not realize it yet but there are legions of Nepalis who are questioning its loyalties post-blockade. During the five months of the Indian blockade the Pahadi community was given to believe, rightly or wrongly, that if not for the unshakable resolve of KP Sharma Oli not to compromise on Nepal's interests the country would have been chopped up into little ethnic ghettos through forced constitutional amendments. Someone like BP could have been able to rebut such simplistic arguments; and given his moral clout and charisma, people would have believed him. But without conviction-driven politicians like BP to lead it, people suspect the loyalty of Congress party whose leaders are known to surreptitiously visit New Delhi and kowtow before their Indian masters.

This perception of a Nepali political party doing India's bidding, real or not, is going to hurt Congress in the next general election, especially among its sizable Pahadi constituencies. CPN-UML leaders will leave no stone unturned during their election campaign to try to paint their Congress counterparts as India's stooges who were ever-ready to trade away national interest in the final leg of constitution making. Congress will have to answer difficult questions like why Sushil Koirala decided to inexplicably stand for prime minister for the second time, in a contest he was sure to lose.

There is no getting around it. During the 13th general convention Congress must find a way to address this image problem. The Pahadi constituencies of Congress are suspicious; a big section of the Madheshis, meanwhile, isn't convinced that Congress party actually works for their benefit. Nor, for that matter, is the Modi government convinced about NC's good faith, not after the fiasco surrounding the promulgation of new constitution on September 20th under the party's leadership.

The next Congress president will thus have a monumental task at hand. India, which has in recent past broken political parties in Nepal at its will, could also try to play in the leadership vacuum in Congress. With a generation of Koirala grandees—the glue that held the party together for so long—now out of the picture, Congress is fair game for such intrigue. Thirteen, Congress could find, is indeed an unlucky number.

biswasbaral@gmail.com

Shows canceled as virus outbreak spooks Asian entertainers