In association with the Nepal National Academy, the Bookworm Trust organised the Second Kathmandu Literary Festival recently. It was a glitzy affair with glittering stars of literature, journalism, politics, academia, and even the silver screen, vying with each other for the attention of lay audiences and enthusiastic participants. For four days in a row, both young and young at heart with intellectual proclivities or literary pretensions thronged to a venue that has lately had come to be better known for Gai Jatra programs.[break]

Five criticism of the event merit some consideration.

The first complaint has to do with the language question. The festival may have had a few international guests, but it was essentially a Nepali program. Hence, the complete absence of the Nagari script from the festival fliers and the venue of functions was an unforgivable omission, especially because the Academy was a co-organizer of the event. Most live talk shows were conducted in Nepali in any case. However, when the corporate world is sponsoring such a program, the predominance of English—the lingua franca of globalisation—has to be taken for granted. Such a lapse can easily be addressed in future events of similar nature.

Accommodating works published in other national languages of Nepal and their authors is somewhat more complex. Forget Maithili, Lepcha, or Tamang languages; the appeal of even Nepal Bhasha is not strong enough to attract and hold a sizable crowd for long in Kathmandu anymore. No matter how fervently language activists wish otherwise, dominance of English and Nepali has to be accepted at events sponsored by corporate interests.

The second comment from a somewhat pretentious audience had to do with the content of the program. Raised in a culture where Sahityik Karyakram (literary program) often meant poetry recitation, reading panegyrics in praise of one’s favourite author, or reminiscing about literary greats of yesteryears, the Nepali audience would take time to learn that everything in life is related to literature. There is literature in what elders discuss at a chautari, activists dissect at a café, and politicos crib about at their roundtables, or what early humans engraved on walls of their caves. Books do not have a very long history in human civilization, and it may not be able to retain its centrality in the intellectual life of the future, either. Literature, however, shall survive changing concerns and continuous transformations in the modes of expression.

The third grouse, coming mostly from authors and their acolytes, was even more ludicrous. It is true that Jagdish Ghimire got to unveil his new book at the prime Dabali venue while release of some equally, if not more, important publications were relegated to some corner rooms of the labyrinthine Academy building. However, that is the way markets function where star power has to be used to the fullest to promote a product as well as the program. A book is not just a carrier of information, ideas and expressions but also a status symbol when consecrated by a celebrity. It is impossible to give equal importance and space to all books, various authors and every publisher at any commercial event.

The fourth kind of comment was in fact a backhanded complement for the organizers. When political colour is given to an event, or when hands are raised to show that most talking heads shared certain political persuasion, it implies that those left out of the proceedings were envious of the limelight hogged by those perceived to have been their opponents. Envy is a sign of success.

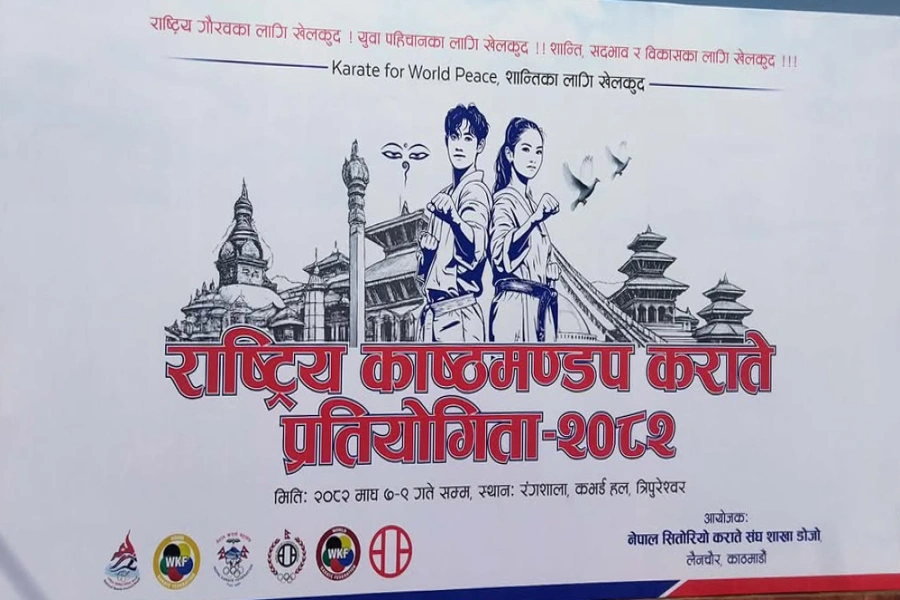

Illustration: Sworup Nhasiju

The fifth observation perhaps requires a little more nuance in analysis. At a program like this, it was natural to discuss everything from sociology to economics and cinema to journalism and a lot many things in between.

However, deliberations over reading culture failed to get the importance it deserves at a literary event. Abhi Subedi did explore various dimensions of discourse between writer, text and reader during his keynote speech. Other than that, the festival had more to do with raw materials for books, which is ideas, than the quality of the final product, the behaviour of consumers or the pattern of consumption.

Sense and sensation

Prashant Jha tried his best to veer Vinod Mehta towards the contents of “Lucknow Boy.” However, the illustrious editor of several successful and not-so-successful publications in the past has spent too many years dissecting other renowned personalities to talk deeply about his own inspirations and motivations. Discussions about the evolution of his outlooks invariably turned towards his metier: Editorship of the Outlook magazine.

At a session with editors of national newspapers, everyone on the panel appeared to be apologetic about their profession. Sudhir Sharma meekly claimed that the media did help in shaping national agenda. Ajay Bhadra Khanal was forthright enough to admit that the only way for English language publications in Nepal to influence policy was in an indirect manner. English publications inform foreigners who then use their clout with public officials to cause course correction.

He need not have been so defensive. While it is true that English is not well understood, Nepali papers are hardly read at all. People form their opinions on the basis of pull quotes; and punch lines read better in a learnt language!

Kishor rightly ridiculed the claims of Sudhir and Ajay, but upon probing from Jagdish Shamsher during the question and answer session, he confessed in a roundabout manner that the main responsibility of an editor was to be the hatchet man of the media owner.

Narayan Wagle was facilitating the conversation. His facial expressions displayed a queer mixture of amusement and sadness, but the former editor of two of the most widely read Nepali dailies managed to retain his composure despite the provocative observations of the seemingly powerful panellists.

Neutrality in analysis is neither possible nor desirable. Objective appraisal, too, implies that an appraiser is clever enough to hide his biases behind compelling arguments. Evaluation is subjective by definition because it is almost impossible to shake off one’s preferences, orientation, tastes, and impressions.

However, it is possible to argue that the session about plays was perhaps the most stimulating of all the proceedings.

Panellists for the Natak Jari Chha (The show goes on) session were intelligently chosen. Abhi Subedi has the unique ability of merging high theory with passionate theatrics in a seamless manner. Dayahang Rai was full of enthusiasm. Khagendra Lamichhane carried himself like a confident conductor. He may not have known how to play all instruments, but he had a fair idea about the thematic music of conversations. Lamichhane knew his panellists so well that his questions seemed to be designed to elicit the responses he wanted.

Sunil Pokharel loves theatre; and love always triumphs over enthusiasm, knowledge or interest. Sunil managed to hold the attention of everyone without making an overt attempt of doing so.

Complexity of context

The most lacklustre session of the festival was perhaps what should have been its central theme: The book reviews.

No disrespect to the panellists—Ajit Baral, Kishor Nepal, and Rajkumar Bania are accomplished individuals in their chosen areas of endeavours—but the session lacked a person to anchor the discussions in a theoretical framework.

Ajit was an iconoclastic reviewer before he climbed on to higher perches, such as editing glossy periodicals and directing literary festivals. Despite his geriatric fixation with flashing flesh on cover pages—someone needs to remind Kishor that lurid details ceased to be erotic way back in the eighties when video parlours started screening pornographic movies in the back alleys of Kathmandu—the editor of Nagarik daily is one of the finest wordsmiths in Nepali language. Rajkumar is such a sensitive critic that he empathises even with writers that he criticises.

The problem with the session was that none of the gifted panellists knew what they were expected to talk about. Book review is a generic term that includes everything from suggestion list for vacation reading to serious ‘reading’ in the way Marx read Hegel, Lenin read Marx, Mao read Lenin, and Che Guevara read all of them to throw everything out of the window and design his own text for the liberation of South America.

Nepali Marxists do not ‘read’; they merely recite academic masters like ritualistically doing the Chandi Path.

That could be the reason why the death of Eric (John Ernest) Hobsbawm (June 9, 1917 – October 1, 2012), perhaps one of the greatest Marxist thinkers of all times, went unmarked in Nepal. The great historian of ideas wrote books to explain and make one understand rather than proffer new scriptures for Communist ceremonies.

A careful reading of any literary work—fiction, ‘fact-tion’(fact and fiction) or reportage—can elicit different kinds of reaction. For most readers, such responses remain private. Some talk about a book they liked or disliked with their friends or colleagues. In the age of social media, the circle has widened to include a large number of onlookers who would probably never read anything longer than a blog anyway.

The job of the reviewer, therefore, is to ‘read’ a book for those in the audience interested in the written words. Such a ‘reading’ can then result in the form of a critic, a general review, an introductory article, a deliberative essay, an impassioned discourse, an objective analysis, an argumentative rejoinder, or even a dispassionate dismissal. To read is to appreciate, understand, empathise, and only then accept, reject, or keep one’s judgement on hold. All reading is interpreting, and if two or more reviewers have offered identical interpretations, in all likelihood, the book has been read with a purpose other than explaining its contents.

Reviewing books is a hard and non-remunerative work. Other than academics, for whom reviewing books for professional journals often fall under the requirements of career advancement, few have time to do full justice to a book, go over its context and content in a careful manner, and then say something to the general audience.

In its Latin root, to review means to see again. The first impression can never be sufficient. Where does the author come from? The question may sound irrelevant, but sometimes it is difficult to read a book without understanding its writer! The best critics have perspective, passion, and a way of placing a book in wider socio-political context, which is why reading the writer becomes an inalienable part of appreciating his or her work. Only when the writer is familiar to a critic, she can write about the book with courtesy but not cravenness, honesty but neither brutality nor compassion, some politeness but also viciousness, if necessary. A reviewer has the duty to offend in a civil manner.

One need not be too discerning to realise that far too many trashy pieces have begun to crowd bookshelves in Nepal. Vanity publications, genealogical accounts of this or that caste and family, travelogues that read like itineraries of an itinerant bourgeoisie, collection of newspaper articles, verses penned by enthusiastic school kids, and reminiscences of those who do not have much to tell and even less to share—a visit to a Nepali bookstore can be exasperating.

Readers need good reviewers to cut through piles of crap. They would have to wait for the emergence of such a breed. Until then, most reviews would continue to be what they are: Puff jobs or pointless pontificating. On that point, the panellists appeared to be almost unanimous.

Maybe the last session of the Kathmandu Literary Festival served its purpose, after all. It showed that Nepal is a long way from claiming a culture of reading. Beginnings are being made, however. In a neo-literate society, that alone is good enough reason to celebrate literary festivals.

Lal contributes to The Week with his biweekly column Reflections. He is one of the widely read political analysts in Nepal.

Helping children enjoy reading