The controversy surrounding the construction of a cable car in Pathibhara, Taplejung district, Eastern Nepal, is now in an entrenched situation. There is a kind of standoff. Both parties to the dispute are digging in their heels, and the negotiation team formed by the government has failed to resolve the dispute after three rounds of talks.

The dispute took a nasty turn after the eruption of violence on January 25, which seriously injured three protesters due to police firing.

The Opponents

Essentially, there are two parties to the dispute—the opponents and the proponents. The opponents, who go by the name of the “No Cable Car” group, consist of 21 varied stakeholders. They are determined to halt the construction of the cable car. Going by media reports, they are willing to stop it at any cost. They are very vocal and are resorting to all possible means and tactics. These include filing court cases, staging street demonstrations, organizing bandhs, lobbying with the media and MPs, launching protest marches, and threatening to internationalize the issue. As a pressure tactic, they have taken absurd moves like picketing Global IME Bank, chaired by Mr. Chandra Dhakal, the key figure behind the cable car project.

The Proponents

Compared to the opponents, the proponents are not as vocal, but they believe they have the backing of local, provincial, and federal governments, as well as business communities and local residents. They are equally determined to move forward with the project.

The Project

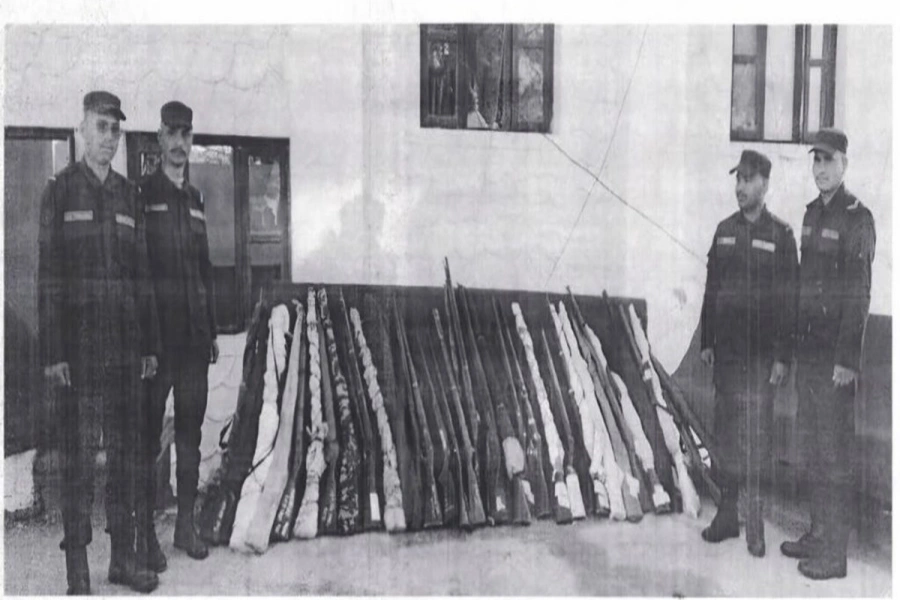

Pathibhara cable car supporters attacked, smeared with black so...

The project itself has been in discussion for three decades. The total cost is estimated to be Rs 3 billion, covering a 2.75 km distance, and is expected to be completed within 1.5 years. It is anticipated to double religious tourism and boost the local economy. The project will reduce a day-long trek to a mere 10-minute ride, benefiting elderly, sick, and disabled pilgrims visiting the Pathivara Temple, who would otherwise have to be carried by human porters—an expensive alternative, with costs depending on weight. The cable car company has the capacity to serve 1,000 travelers per hour. The project is currently under construction.

Differing Viewpoints

Both groups have diametrically opposite viewpoints. If one group is determined to proceed with the project, the other is equally determined to halt it. The truth or a win-win solution must be found somewhere between these two extreme positions.

The primary concerns of the opponents are that the project entails heavy environmental costs (deforestation of thousands of laligurans trees), damages religious sentiments, and displaces cultural heritage. It could also take away jobs from local porters and hoteliers. They argue that the project amounts to robbing common property for the benefit of a few powerful and well-connected individuals.

The proponents of the project believe they have immense support from the locals. They highlight the potential development benefits, particularly in attracting large numbers of religious tourists from neighboring India. They also accuse the opponents of being outsiders who are politicizing the issue for their own narrow, vested interests.

In an environment of extreme distrust and rivalry, it is often difficult to determine who is right and who is wrong, or what is justifiable and what is not. This case represents a typical conflict between environmental and developmental goals; between public and private interests; between outsiders (looking in) and insiders (looking out); and between the preservation of traditional cultural values, natural heritage, and modern development needs. The truth must be found somewhere between these two extremes.

The opponents should recognize the possible social, economic, and political consequences of halting the project. The impact could extend far beyond what is immediately visible, particularly in terms of development and investment in Eastern Nepal.

The government also faces risks from project non-implementation. A forceful continuation of the project could further entrench the political impasse that is already taking a toll on Eastern Nepal. Labeling the opponents as “enemies of development” is not a rational solution. Some political actors are already attempting to exploit the situation to ignite religious and communal tensions.

As an alternative, the opponents have suggested road construction, improvements to existing road infrastructure, or investments in other underdeveloped areas to boost the economy. However, the reality is that this is a private company driven by investment opportunities, market potential, and, above all, profit motives. The opponents may cry foul, but the company has secured the necessary permits to proceed. Without some form of compensation, it is nearly impossible to stop construction. The situation is undoubtedly complicated.

Winners and Losers

All development interventions create winners and losers—over time and across different regions. Remember, the construction of the Prithvi Highway took away jobs from thousands of locals in the “By Road” (Daman area). Similarly, the construction of the B.P. Highway displaced thousands in the Mugling area. Who knows what consequences the completion of the Fast Track Road may have on the B.P. Highway? Have we ever deeply considered what happened to the displaced Tamang community after the construction of the Kulekhani Dam?

When launching development interventions, the guiding principle should be the sacrifice of a few for the greater good. However, those who make sacrifices should be compensated from the gains of the many. For too long, in the name of development, Nepali people have been cheated. The Ranas, Shahs, Panchas, multi-partywallahs, and now the republicans have usurped power and exploited the people. Development has always meant greater benefits for a small, powerful elite at the cost of the larger community. In such an environment, skepticism, cynicism, and pessimism are natural responses.

Remember, the opponents are accusing the proponents of reducing their sacred Mukkulung to “a dating spot.” It may seem absurd, but the underlying concerns need to be explored.

Possible Way Out

What could be a possible way forward? One option is to expand rather than limit the project, so that larger concerns can be addressed. This could include widening ownership structures, addressing environmental and sustainability issues, guaranteeing local income and employment opportunities, and ensuring economic efficiency and fair distribution of benefits.

This calls for a true social cost-benefit analysis of both the proposed and existing cable car projects. So far, cable car projects have primarily focused on promoting limited religious and recreational tourism. They rely on captive markets with little focus on backward and forward economic linkages. Tourism, by definition, is a service industry that primarily serves the elite and the well-off. Moreover, service industries notoriously contribute to economic inequality.

Without state intervention to ensure environmental protections, compensate local businesses and workers, and mitigate economic disparities, a purely market-driven, neoliberal approach to the problem could lead to disaster. Remember, markets are not always perfect—and this is especially true in Nepal.

-1200x560_20240917101949.jpg)