On Oct. 5, 1990, French mountaineer Christine Janin became the first French woman to summit the peak of Mount Everest. She climbed the Earth’s highest mountain with a team composed of mostly French women, which was one reason Pasang Lhamu Sherpa stood out.

Pasang wasn’t French. She belonged to an ethnic group renowned for its prowess on the sharp and jagged peaks of the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges. She was Sherpa.

Most of the French women on Janin’s team reached Everest’s peak, too. But on that day, Pasang would not summit. It wasn’t due to her lack of skill and fortitude. No, Pasang was ordered down by a man.

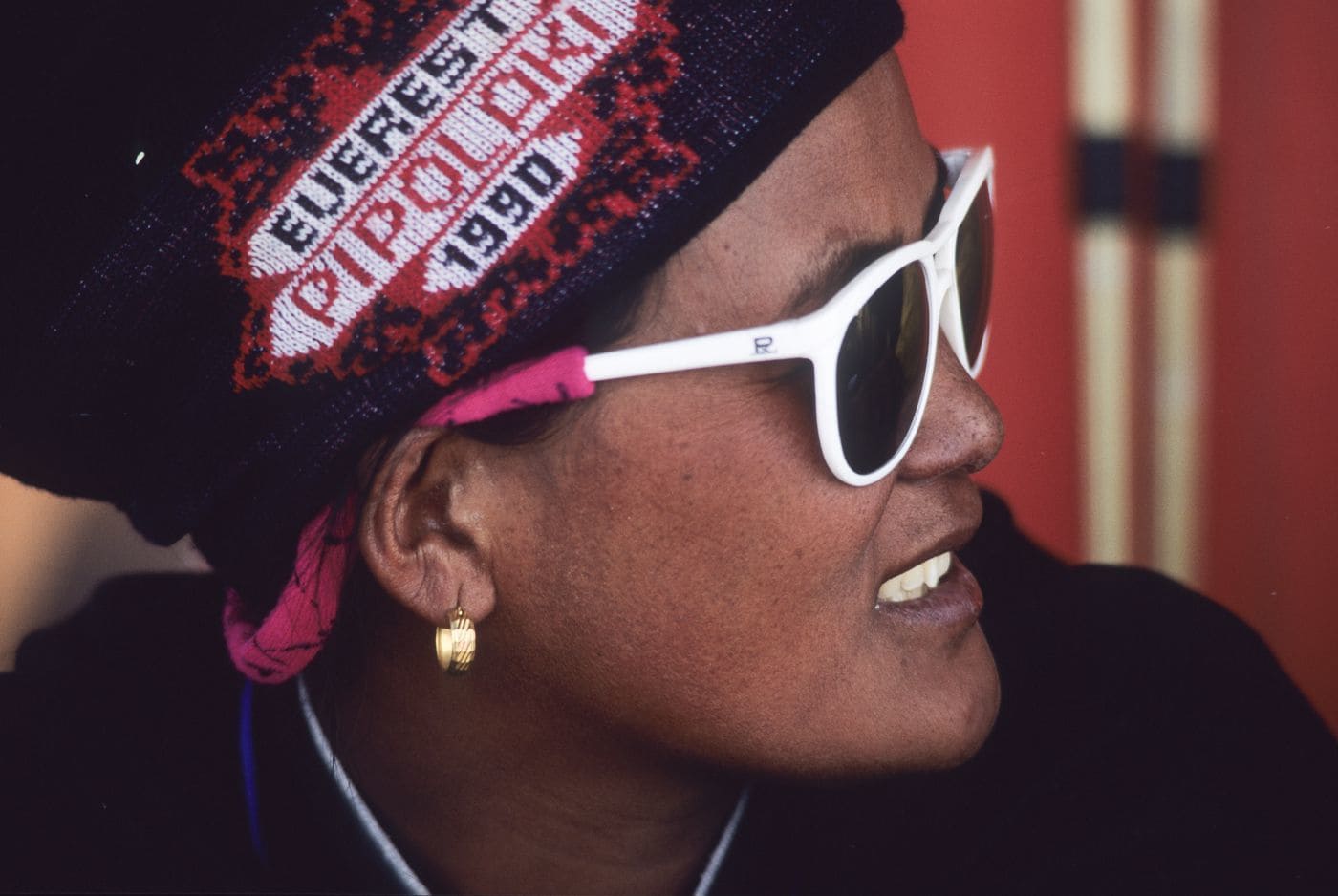

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa on her first Everest attempt in 1990. (Pascal Tournaire)

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa on her first Everest attempt in 1990. (Pascal Tournaire)

Just after Janin summited, Marc Batard, the Frenchman who led the expedition, demanded that Pasang descend before summiting. She was taking up too many resources, he said. But Batard likely had a different reason: He did not want the triumph of a white French heroine to be eclipsed by a brown Nepali one. If Pasang had reached Everest’s peak that day, she would have become the first Nepali woman

In later interviews, Janin said that perhaps Batard had never expected Pasang to get so far. Batard thought of her as nothing more than a “housewife and a mother,” he explained.

Pasang was married and a mother to three children. But she was also a determined mountaineer who had spent her life defying societal norms. Batard was only a hurdle. Still, he taught her an important lesson that she would tuck away in her mind: A climber has to be in control of the expedition to get a spot at the summit.

Eventually, on April 22, 1993, Pasang did summit Everest. It was a glorious day for Nepal, but the light quickly vanished when Pasang died on her descent. The people of Nepal mourned her death then, but they will celebrate the 25th anniversary of her climb today.

Guide team scales Everest at start of spring season

Statue of Pasang Lhamu Sherpa in Kathmandu. (Pascal Tournaire)

Statue of Pasang Lhamu Sherpa in Kathmandu. (Pascal Tournaire)

Pasang’s story is one of determination and tragedy, but it’s not widely known outside of Nepal, San Francisco-based filmmaker Nancy Svendsen said.

For the past eight years, Svendsen has been working on a documentary about Pasang, a woman who simply refused to accept the diktats of the men around her. “The Glass Ceiling: The Untold Story of Pasang Lhamu Sherpa” is set to release this summer. Svendsen’s brother-in-law, Ang Dorjee Sherpa, is Pasang’s oldest brother whose stories about his sister captivated and inspired Svendsen.

“The Glass Ceiling,” which Svendsen went on to direct and produce, is “the story of a freedom fighter,” she said. After all, Pasang almost always persevered, no matter what stood in her way.

Like many Nepali women, Pasang dealt with the constraints of her culture, which doomed women to the domestic and familial. Although her brothers went to school, Pasang received no formal education. Being part of an ethnic minority in Nepal didn’t help matters.

“Society around her told her that Sherpas were the lowest of the low,” Svendsen said. But Pasang thought otherwise.

Her first major act of rebellion came when she was a young woman facing a marriage arranged by her family. Pasang refused to marry someone her family had chosen for her. Instead, around 1979, she left her small village in the Himalayas for Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal, with a partner she chose for herself: Lhakpa Sonam Sherpa. The couple began a trekking company that worked mostly with Western climbers. As they built their business, Thamserku Trekking, Pasang began to see an opportunity that extended beyond her domestic duties.

She could see a path to Everest. Through Thamserku Trekking, Pasang met Batard, who invited her on the 1990 expedition but thwarted her attempt to reach the peak.

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa on her first Everest attempt, in 1990. (Pascal Tournaire)

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa on her first Everest attempt, in 1990. (Pascal Tournaire)

Not long after, Pasang had the opportunity to climb with an Indian women’s team. While she initially agreed to join the team, Pasang backed out when she learned she would not have a leadership spot.

She began to raise money and find sponsorships for an all-Nepali expedition, perhaps the only sort then, that would allow a woman to have a leadership spot. In the fall of 1991, Pasang, her husband and a strong team of Sherpas attempted to climb Everest. This time, the weather stood in their way. They encountered a storm close to the peak, forcing them to bivouac in whiteout conditions and return to base camp. When Pasang tried again in 1992, she was once again held back by weather.

“It must have been an excruciating moment,” said “The Glass Ceiling” executive producer Alison Levine, a mountaineer who has summited Everest. When Levine heard about Pasang’s failed attempts, she could “immediately feel the pressure that Pasang was under.”

“I know what it is like to try and try again,” Levine said. Pasang’s breakthrough came in 1993. By this time, she had “built up a loyal following who believed in her,” Svendsen, the director, explained.

“The country needed a hero, and she exemplified the belief that [a Nepali woman] could be someone,” Svendsen added. This time, Pasang “was climbing for the country and for women.” With an all-Nepali team, she succeeded.

On April 22, 1993, at 32, Pasang became the first Nepali woman to summit Everest.

After Pasang summited with six other Sherpas, they began their descent, eventually splitting up into two groups. Pasang was in the last group with Pemba Norbu and Sonam Tsering Sherpa.

But Sonam Tsering, who had been coughing up blood the day before, became sick. They stayed with him overnight, their oxygen supply depleted. Pasang sent Pemba Norbu down the mountain for more oxygen, but when a storm blew in, he wasn’t able to return. No one would be able to get to Pasang and Sonam Tsering for days.

As an anguished Nepal, which had been following the course of the expedition, waited, the prospects of their return faded. The length of the storm made rescuing her impossible. The two died on the mountain. Days later, Pasang’s body was carried down by Macedonian climbers. Her funeral was a moment of mass mourning, with thousands participating. Svendsen, who has incorporated footage of the funeral into the film, called it an “unprecedented cultural event.”

Even in death, Pasang was noble. She could have left her sick summit partner on the mountain instead of staying with him. Indeed, many foreign mountaineers believe that the plight of ailing climbers must be ignored to get to the summit or to safety. (“You have got to keep moving or die at this extreme altitude,” British mountaineer Alan Hinkes said in 2012. “If someone has died, there is not much to do about it.”)

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa in 1992. (Elsina Bolt)

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa in 1992. (Elsina Bolt)

Mountaineering attracts an ambitious and determined lot, and, in the absence of compassion, both of those can devolve into self-serving and rabid egotism. Because it’s expensive to climb Everest, it tends to attract wealthier individuals. Have $10,000? That won’t even cover the climbing permits.

“Western climbers go to Nepal and pay a lot of money to go on these expeditions,” Svendsen said, “but it is really the sherpas who make it possible. [They] take on a disproportionate amount of risk.” When Sherpas act as guides and porters, they go up the mountain before the climbers, carrying all the equipment to set up camp and ensuring conditions are good for those that come behind them.

When Pasang summited, she took on the risk for herself. She navigated her own path to the top, even if, along the way, she faced Western condescension and defied her own culture.

“Her’s is a universal story,” Svendsen said. It’s “one that has the power to really change people’s lives and inspire women to really do something.”