It is unlikely that powerful bureaucrats in Bangkok, neo-liberal politicos in Jakarta, established professionals in Kuala Lumpur, go-getter entrepreneurs in Hanoi, or uppity salarymen of Tokyo have all even heard of West Virginia, let alone experienced its charms.[break]

However, many of them take to the karaoke mike once the last round of drinks—“real last one, only one more, the one for the road, don’t refuse please”—have been ordered.

The tune is so melodic, so evocative of an aching urge to go back to the roots, that even those who don’t understand any word of English other than ‘home’ are prompted to hum along as Denver emotes: “Almost heaven, West Virginia, / Blue Ridge Mountains Shenandoah River, / Life is old there. / Older than the trees, / Younger than the mountains, / Growin’ like a breeze,” and then the soul-piercing imploring, “Country roads, take me home. / To the place I belong. / West Virginia, mountain mama / Take me home, country roads./”

It is possible that there are identical tunes in Thai, Indonesian, Malaysian, Vietnamese and Japanese folk traditions that remind listeners of moonlit nights, golden dawns, sunny days, dusty dusks and autumn evenings azure in natural light. Country music that celebrates the change of seasons and rites of passage of human life are common to most rural cultures; and almost all cultures have pastoral and agricultural roots anyway. Deep inside, every urbanite is either a runaway from his countryside or longing to escape to the imagined rusticity of village landscape.

Years—nay, decades—ago, somewhere on the banks of the Karnali-Ghaghara River in the mid-western mountains of Nepal, a highly placed Japanese professional had heard drumbeats in the middle of the night and remarked that the music had reminded him of his ancestral home on the hills that his father had left behind to build a successful career in Tokyo. Somewhat a similar comment was made years later somewhere near the source of the Kamala-Balan River when another Japanese veteran of Second World War and an experienced engineer had shed tears in remembrance of fishermen’s songs that seemed to have thrived in Nepal but had almost disappeared from his country.

Perhaps music has the power to evoke reoccurring memories because it takes the listener to the secret recesses of his mind where the silence is so complete that only the sound that the heart wants to hear can reach him. Somehow, the idea of home opens the doors of such niches more effectively than anything other than musical notes and the wafting aroma of favorite spices. Together, the three—music, home, and fares of home cooking, though not necessarily in that order for everyone—has the power to move almost any human soul.

There comes a time when each one of us long to go back to where we came from—to the womblike “native place,” the land called Ghar. Like love, home is a many-splendored—God bless physician-writer Han Suyin for the beautiful adjective that uplifts an everyday noun like ‘thing’ to the stratosphere of multihued imaginations—idea.

For doctrinaire Marxists and dogmatic devotees of market fundamentalism alike, home is merely an ideological construct. In the physical sense of the term, home is where one happens to live—with some sense of permanence, though which is unlikely to be found in hotel rooms or hospital beds—for the moment.

However, home is also more than a place of residence. Home indicates a complex combination of experiences, emotions, desires, frustrations, and many other sentiments that have no word as yet in most written or spoken languages. Their meaning can only be captured in tears and silences. Suyin’s phrase is more appropriate: Like love, home indeed is a many-splendored thing.

Memories and dreams

Home lies in memories. It is real, imagined, remembered and longed for—all at the same time. Perhaps that is the reason homo sapiens—dating back to their ancestors in the caves—have yearned to get back home from time to time.

For people of the Middle Age tribes and their amorphous cohorts do display tribal characteristics in evolving societies, and home is the place where remembrances, expectations, achievements and disappointments blend to form an imagined reality of sorts. Home is the mark on the elbow that was broken while climbing a Jamun tree; of stealing guavas from neighbor’s orchard with childhood buddies and then handing over the entire haul to the prettiest girl in the group; of swimming in the swollen river and being rescued by onlookers; of wading in rice paddies to catch a Gadai fish; of swinging from mango trees in the rains; of swaying with bamboos in the fear of snakes supposedly hiding in earthen mounds; of the warmth of the hearth in winter; of chasing butterflies in mustard fields; and of taking buffaloes for cooling in the mud of the nearest swamp in the middle of summer when ponds had lost much of their water.

Home is also the first alphabet written on the ground that had been swept with red earth; of arithmetic tables learnt by rot; of homework not done, and canes made from the thinnest branches of Karbir flower plants; of a poem that had won accolades of the wise and the learned elders at a nearby town; of dark nights watching Ram Lila; of panoramic views of rural Mela visible only from the vantage point of one’s father’s shoulders; of elation over preliminary results or disappointment over the final mark-sheet; and of the hesitant decision to go out in search of better opportunities.

Home is a place where one can fake to be successful and friends would feign to believe your claims so as not to dampen your festive spirits. It is the place where you can be pretentiously arrogant or brutally honest without any fear of facing resentment or pitiful glances. Who does not want to go back to such a place where one can be a child all over again, irrespective of her age? With the accompaniment of a simple acoustic guitar, Denver’s “Take me home…” has the power to transport the soul to just such a place of one’s belongingness. Whether in fulfillment or frustration, a heart finds solace only in the safety of the remembered home.

Contrary to the claims of the conservatives of all ilks, values are not static. Values do change and have certainly changed, whether for better or worse is a matter of convictions and opinion. But the pull of home has not dampened despite its diminishing place in modern life. After all, to the heart of a rational and upwardly mobile urbanite—the homo economicus in libertarian language—nothing is dearer than the latest iPhone, nothing sexier than the trendiest of i20s, and nothing more pressing than EMI of loans taken to fund all such objects of desire.

However, there comes a time when yuppies are no different from their country bumpkin cousins in itching to go back to their roots. Happily, festivals offer a socially acceptable occasion to withdraw from the rat race—no matter whether slow or fast – and for a house mouse or a sewer rat, the competition of modern life produces far more losers than winners. In the conceptualization of sociologist David Emile Durkheim, anomie is an inescapable part of ‘free’ life. Home is the ‘un-freedom’ that humanity seeks to anchor itself in life.

Dashain exodus

Theoretically, it is possible to go ‘home’ at any time of the year. Festive occasions, however, create a perfect excuse for extended families, friends and communities to gather at almost the same time of the year at the place of shared experiences. Religious importance apart, what better time of the year for Nepalis to travel when rains have stopped, rivers have receded, snowfall is yet to start, and days are perfect to walk in the sun in the hills while nights offer brilliant sights of star-studded skies in the Tarai? Everybody who can afford a vacation needs one.

The Dashain exodus from Kathmandu Valley has already begun. It will continue right up to the Ashtami, the eighth day of Dashain festivities, marked by ritual sacrifice of wailing or stupefied animals at midnight. After a relative lull of two days when even bus operators take a break for celebrations at home, once again there will be a mini rush between Dashami and Kojagrat Purnima when semi-permanent residents of the Valley will visit their grandparents, in-laws or maternal uncles for Tika blessings. The number of people coming back to the Valley, however, equalizes the second phase of temporary out-migration. Only a few nowadays extend their Dashain vacation to Tihar and Chhath.

Dashain is a ritual worship of the Mother Goddess and has to be performed at ancestral shrine or family home. Lakshmi Pooja, however, can be done wherever one lives and works. Lakshmi is the goddess of prosperity, and she probably prefers the worksite to the place of one’s origin. Bhai Tika is more of a social ceremony and can be done at a place of convenience for sisters and brothers. Chhath Pooja is ritual homage to the elements—earth, water, sun, ether, and air—and devotees can perform it wherever they can find a clean water body.

Muslims, too, would be traveling to their ancestral places for Eid ul-Adha—Bakri Id in everyday language—that falls during the Dashain vacations this year. Then there will be a long wait for Christmas and New Year festivities. Like Deepawali, Christmas festivities have been thoroughly taken over by the market forces, and these occasions fail to pull people back to their roots. That, however, is a different and long story.

So many residents of the Valley will not be able to go back to their familial homes in the mountains, valleys, hills and plains this Dashain and Tihar for various reasons. There are a few achingly soulful songs like “Ekadashi Bajaraima” in Nepali, but the country needs many more, especially for the solace of the ones who long to go but cannot make it to their places of belongingness.

Thank God for small mercies, though: At least for a few days, there will be no cacophony over consensual politics. Tea party parleys would probably resume from Kojagrat Purnima. Till then, there is ample time to attune our ears to the forgotten sound of silence—the music that we learn not to recognize as we grow into adulthood—and listen to the indecipherable but heartrending cries of sacrificial animals and birds.

Meanwhile, it is the magic of Denver again: “Misty taste of moonshine, / Teardrops in my eye. / Country roads, take me home, / To the place I belong.”

Then the existential question: Where do nowhere people belong?

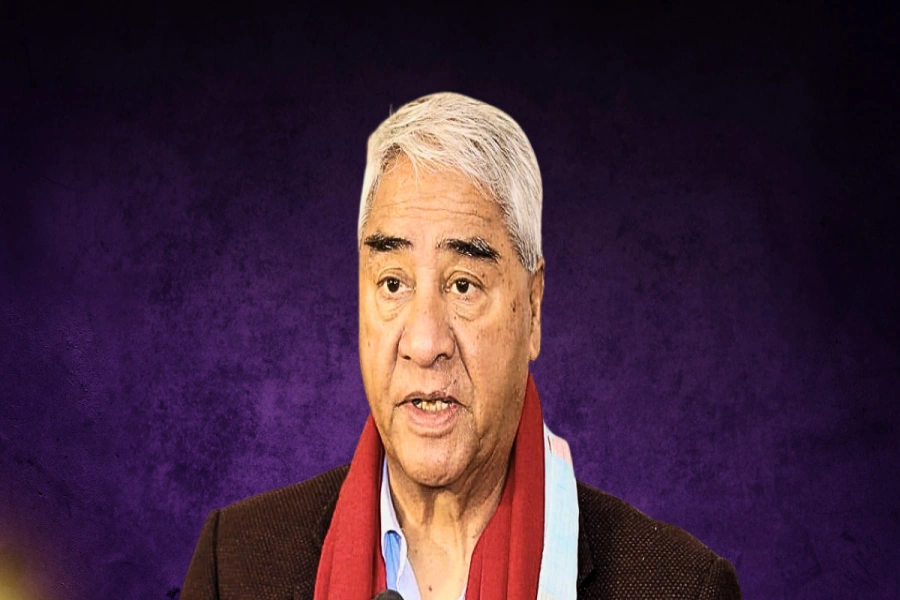

Lal contributes to The Week with his biweekly column Reflections. He is one of the widely read political analysts in Nepal.

14th Nepal Festival in Tokyo today