Indian and Pakistani curiosity in the Eurasian group is understandable. But why is Nepal interested in joining?

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is a curious beast. Under the veneer of economic cooperation, it is essentially a military grouping envisioned as a counterweight to NATO, the US-led military alliance. The group’s two main backers, Russia and China, have seemingly separate goals. China is mainly interested in the economic component of greater cooperation in Eurasia as it looks to revive the old Silk Route. Russia, meanwhile, feels threatened by America’s growing engagement in it's near abroad following the end of the Cold War. With China also worried about possible American encirclement, it was perhaps natural for Russia and China to together fight American ‘imperialism’ in Asia.

Formed in July 2001, the organization had six inaugural members: China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kirgizstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. While the first five were already in a kind of informal grouping called Shanghai Five since 1996, Uzbekistan joined in 2001, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization was formally proclaimed. Even before its 2017 expansion, with Russia and China already in its ambit, the organization had considerable military and economic heft. Now with the formal entry of India and Pakistan as full member states this June, the SCO has been transformed into an economic and military juggernaut: the new eight-member bloc accounts for nearly half the global population and a quarter of its GDP.

The entry of India and Pakistan in the organization is the perfect illustration of the kind of subtle geopolitical games between big powers that have characterized post-9/11 Asia. Russia wanted India in because it was worried about China’s growing clout in Central Asia. It greatly troubles the Russians that the Uzbeks and Tajiks these days are more reliant on Chinese investment than they are on Russian petrodollars. In Russian calculation, India, perhaps Russia’s only all-weather friend in the region, would help check China’s growing footprint in Central Asia and the Caucuses.

Indo-Pak rivalry revisited

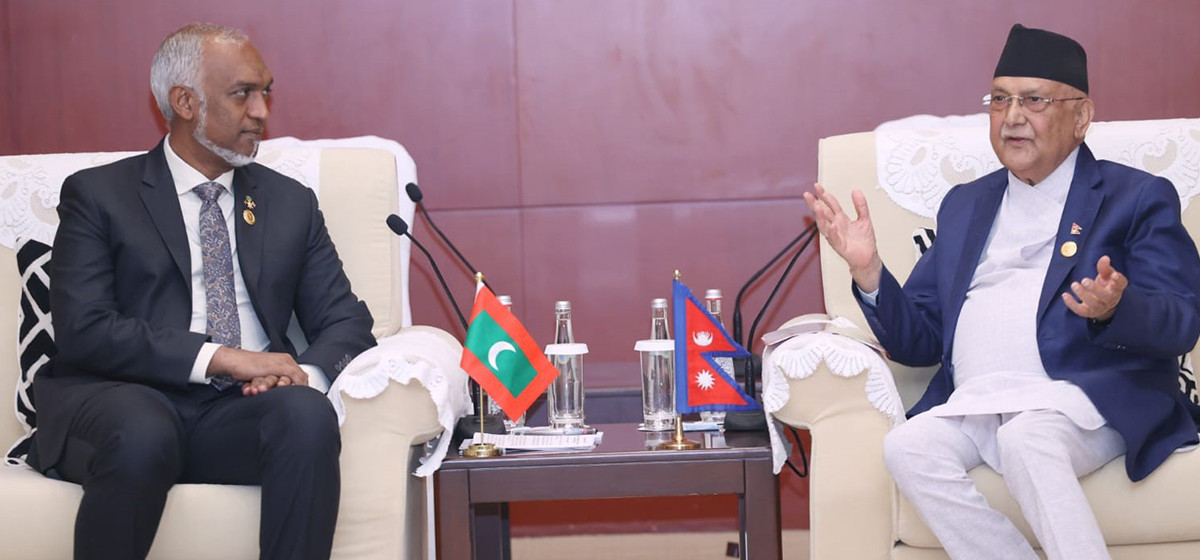

PM Oli raises Lipulekh objection in meeting with Xi, seeks Chin...

But if Russia wanted India in the SCO, China argued, the Russians should also agree to include Pakistan, China’s own all-weather friend, and a compromise was reached. The two South Asian countries, for their part, seem to have calculated that there are enormous gains to be made by tapping into the vast natural resources of Central Asia. Pakistan, in particular, has been desperate to diversify its foreign relations after India’s bid to isolate it in South Asia, in the process making SAARC, whose biannual summit Islamabad was supposed to host in 2016, nearly defunct.

Indian and Pakistani curiosity in the Eurasian grouping is thus understandable. But why is Nepal interested in joining? Currently, Nepal is one of four ‘dialogue partners’ in the SCO, along with Armenia, Azerbaijan and Cambodia—and angling for more.

“It was Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala who first showed an interest in the SCO soon after its formation in 2001,” said Upendra Gautam of the China Study Center. “At that time, the price of oil in Nepal had been steadily increasing. Koirala thought it would be wise for Nepal’s energy security to explore Central Asian oil markets”.

But while Koirala’s intent was right, subsequent governments failed to take any initiative to import oil from Central Asia via China, if such an arrangement was at all feasible. Gautam blames Nepal’s “reactive diplomacy” for this as, otherwise, Nepal stands to “immensely benefit” from SCO, at a time the SAARC is in limbo. At least two other people I talked to were of the view that the SCO is much better at delivering compared to SAARC, and as such Nepal should not fail to tap its enormous potential.

But not everyone is convinced. “Nepal has this tendency of getting into glamorous-looking international organizations without any homework,” said Keshab Prasad Bhattarai, a senior research fellow at Nepal Institute for Strategic Studies (NISS). “Like it or not, the SCO is an anti-West lobby. Has Nepal calculated the cost of its greater involvement there?” Bhattarai thinks Nepal is committing a big folly by joining a geopolitically-loaded organization without first clearly defining its foreign policy priorities.

Doing it right

Although these views may seem contradictory, they are not. They suggest that Nepal should first clearly chart out its foreign policy priorities and only then look to engage with the rest of the world based on those priorities. There is a clear case for Nepal’s greater engagement in the SCO if, for instance, Nepal makes import of petro products via China a foreign policy priority. It can then negotiate with China, via SCO or bilaterally, on getting part of the natural gas that China has been bringing through the Turkmenistan-China natural gas pipeline since 2009. As new sub-lines are continuously being added to this pipeline, perhaps Nepal can negotiate to bring one of these lines up to the Nepali border or, short of that, get to import, by road or rail networks, the Central Asian gas that is already in China.

But again that should only be done as a matter of Nepal’s foreign policy priority. As Bhattarai of NISS suggested, the Western countries see the SCO as basically aimed at limiting their strategic space in Asia. Nepal, long reliant on US and European aid, will thus need to tread carefully.

Addition of India to the SCO should, in theory, be a cause for cheer for Nepal, for the organization now gives Nepal yet another platform to pitch its role as a dynamic economic bridge between India and China, both now members of the Beijing-based grouping. Yet it is also hard to see this trilateral idea fly without India shedding its old suspicion of ‘Chinese designs’ on South Asia.

Writes Suyash Desai of Jawaharlal Nehru University: India has to wait and watch if its membership in the SCO will come “at the expense of China’s interest in Indian-led organization such as BIMSTEC or SAARC”.

India is still determined to protect its sphere of influence in South Asia. China wants to penetrate this Indian armor. And Nepal cannot alienate either. Nepal thus cannot afford to be seen as riding on the coattails of either India or China as it seeks a greater role for itself in the SCO. Easier said in the middle of elections being seen, in part, as a referendum on Nepal’s foreign policy.

biswasbaral@gmail.com