Women who experience recurrent miscarriages may be good candidates for IVF with preimplantation genetic screening (PGS), which enables fertility specialists to test an embryo for genetic and chromosomal problems that can lead to miscarriage. Those couples who have struggled with recurrent miscarriage, failed IVF, or unexplained infertility can strongly prefer PGS to help identify chromosomally-sound embryos for transfer back into the uterus.

Childbearing and raising children are extremely important events in every human’s life and are strongly associated with the ultimate goals of completeness, happiness, and family integration. It is widely accepted that human existence reaches completeness through a child and fulfills the individual’s need for reproduction. Human fertility, compared with other species of the animal kingdom, is unfortunately low.

According to recent studies by the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 8-10% of couples are facing some kind of infertility problem. Infertility, a global health issue, can be defined as the incapacity to fulfill pregnancy after a reasonable time of sexual intercourse with no contraceptive measures taken. It is a multifaceted issue with social, economic, and cultural implications, which can take threatening proportions in countries with strong demographic problems, such as Nepal. This increase could be due to a wide spectrum of factors such as delayed childbearing, alterations in semen quality due to habits such as cigarette smoking and alcohol, changes in sexual behaviors, and many more. Equally, infertility may affect the relationship of couples with their families, friends, and each other, and may decrease their self-confidence with feelings of guilt and insufficiency.

Due to imbalances caused by the current sedentary stressful lifestyles, there has been a gradual increase in the number of visits to infertility clinics especially in the last decade or so. In the present context, the availability of world-class in-vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment is growing adaptability in terms of changing perceptions towards its management. IVF, the most effective form of assisted reproductive technology (ART), is a complex series of procedures used to help with fertility or prevent genetic problems and assist with the conception of a child. It is the treatment of choice for unresolved infertility.

Nepal must diversify the genetic landscape in coffee production...

Today, IVF is practically a household word. But not so long ago, it was a mysterious procedure for infertility that produced what was then known as "test-tube babies." Louise Brown, born in England in 1978, was the first such baby to be conceived outside her mother's womb. In addition, the IVF technology revolutionized the field of reproductive medicine and helped millions around the world struggling with infertility become parents. More than 400,000 babies from 1.6 million ART cycles are born around the world every year. To date, it is reported that over 8 million babies were born through IVF.

Unlike the simpler process of artificial insemination -- in which sperm is placed in the uterus and conception happens otherwise normally- IVF involves combining eggs and sperm outside the body in a laboratory. Once an embryo or embryos form, they are placed in the uterus.

The success rate of every treatment depends on various factors and similar is the case with the IVF treatment. Likewise, success rates for IVF depend on several factors, including the reason for infertility, age of the woman, where you're having the procedure done, whether eggs are frozen or fresh, whether eggs are donated or are your own, and your age. A woman's age is a major factor in the success of IVF for any couple. For instance, a woman below 35 who used her eggs had a 37.6% chance of having a singleton (one baby) using IVF, while a woman between ages 41 and 42 had an 11% chance. The success rate climbs with more egg transfers. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that the success rate of IVF is increasing in every age group as the techniques are refined and doctors become more experienced.

Although the breakthrough of ART has improved outcomes for struggling couples, a new challenge has emerged: recurrent implantation failure (RIF). There is no accepted formal definition for RIF; many of the scientists suggest that it is after three failed in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET) cycles with good quality embryos transferred. RIF refers to cases in which women have had three failed in vitro fertilization (IVF) attempts with good-quality embryos.

RIF is an extremely frustrating condition for both patients and clinicians and its treatment constitutes one of the most difficult challenges in the field of IVF. Possible causes of RIF include wrong lifestyle habits (i.e., smoking and obesity), low quality of gametes (in particular in older women), thrombophilia, uterine factors (i.e., congenital uterine anomalies, endometrial polyps, submucosal fibroids, intrauterine adhesions), and adnexal pathologies (i.e., hydrosalpinx). However, in the great majority of cases, the etiology remains unknown.

Therefore, women who experience recurrent miscarriages may be good candidates for IVF with preimplantation genetic screening (PGS), which enables fertility specialists to test an embryo for genetic and chromosomal problems that can lead to miscarriage. Those couples who have struggled with recurrent miscarriage, failed IVF, or unexplained infertility can strongly prefer PGS to help identify chromosomally-sound embryos for transfer back into the uterus. On day five or six after fertilization, the embryologist will remove a few cells from the developing embryo that will be used to verify the presence of all 23 chromosomes. The cells are taken from the part of the embryo that will later form the placenta. The results will allow the selection of embryo/s with a normal number of chromosomes. These embryos are more likely to result in an ongoing pregnancy with a lower risk of miscarriages, allow the doctor to transfer only healthy, chromosomally normal embryos to the uterus, dramatically reducing the chance of miscarriage and enhance the possibility of fertilization.

PGS, one of the prevailing latest applications in the optimization of assisted reproductive technologies, provides prenatal genetic diagnosis before implantation, thus allowing detection of genetic defects and their exclusion from embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technologies. PGS allows studying the DNA of eggs or embryos to select those that carry certain mutations for genetic diseases. It is useful when there are previous chromosomal or genetic disorders in the family and within the context of IVF programs. Over the years, several methods were developed to define the number of copies of each of the chromosomes. Among many of the other earliest practices, next-generation sequencing (NGS) is the latest technological breakthrough in pre-implantation genetic testing. NGS is well accepted in the prenatal testing arena and recently applied to PGS. It allows us to study all 23 pairs of chromosomes at a more comprehensive level, and with deeper resolution. Studies demonstrated that NGS can detect embryos with unbalanced chromosomal translocations.

Besides, it provides screening for disorders such as Down Syndrome or Turner Syndrome which are caused by an abnormal number of chromosomes in certain positions. Chromosome disorders typically are not inherited and are more likely to happen when parents are older, especially the mother. PGS does not screen for specific genetic disorders which are inheritable, such as Tay-Sachs disease or cystic fibrosis. False positives and false negatives are possible, although the risk is less than one percent. The test isn’t able to study every chromosome, so it cannot guarantee you will have a healthy baby. This is why your obstetrician may recommend prenatal testing a bit later in the pregnancy to screen for chromosomal abnormalities.

The past several decades have seen tremendous advances in the field of medical genetics. The application of genetic technologies to the field of reproductive medicine has ushered in a new era of medicine that is likely to greatly expand in the coming years.

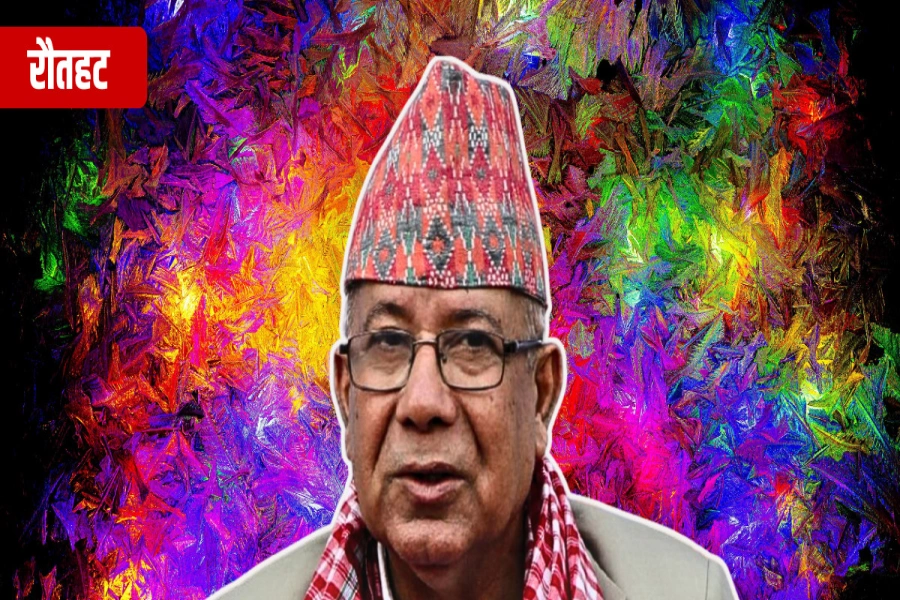

(The author is a research officer at Kathmandu Center for Genomics and Research Laboratory.)