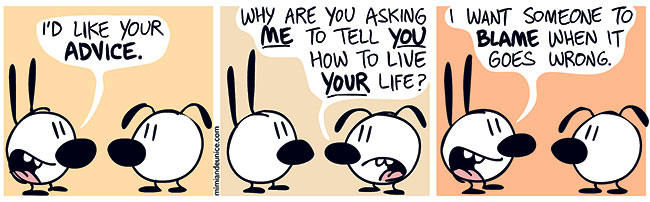

If there is one thing everybody excels at (and I’m also guilty of this one) it is giving advice. From tips on how to save your outdoor plants from the torrential rain to how to become more productive, there is a lot of advice that is thrown at you (or that you throw at others) on a daily basis. And much of it, as I’m sure all of you already know, is useless chatter – words carelessly uttered to fill in the gaps and sometimes also to overpower and dominate. If everybody knew everything, why aren’t our lives perfect?

There was a time when I used to listen to people, nod at everything they said like it was the Holy Grail, and then forget all about it the minute the conversation was over. That was my survival tactics at parties and family functions where, inevitably, I’d get a lot of ‘nonsense’ tossed my way. After all, everybody was an expert on how I should be doing things. There was a better way I could do my hair, and why didn’t I put toothpaste or a neem leaf on that nasty looking pimple? Oh, and what do I feel about meditation and yoga? It looks like I need it since I’m so hyperactive. A relative told me it would really help me prosper in my career too. Like she, being an engineer, knew all about marketing!

From oily to dry: Beauty diet for healthy skin

There’s no stopping all that comes your way. And sometimes you also can’t stop yourself from giving advice to people either. Why is your aunt wearing such high stilettoes when it’s sure to give her a backache later on? You must tell her to wear wedges because you have been doing so for a while now and it’s the most comfortable and stylish shoe design that’s out there. You must tell her for her own good. And just like that I become one of the many people who know what must be done and how.

But despite all that, what I have learned is advice can be a powerful tool. I’ve also learned that there is an art to both giving and receiving advice. And it’s mostly because a lot of advice is given in a very I-know-it-all and what-do-you-know mindset that it falls on deaf ears even when the intention behind it is actually good. There are apparently some rules at to giving and taking advice that benefits both the parties involved. There’s also an art to how you ask for advice so as to get the most out of the exchange. It needn’t be a futile and much dreaded experience.

One of the simplest ways to do that, I’ve come to realize, is to tell people what worked for you without telling them they should do the same thing too. Let them decide what they want to do – whether they want to take the route you did or do something different altogether. At least, by sharing your story, you have armed them with the information they might find useful. Also, seeking advice can be your greatest learning experience. We are surrounded by really smart people who have knowledge and experiences that we don’t have. Why not reach out them sometime and pick their brains? This takes humility and trust. Granted you might not always get what you were looking for but everyone has had unique experiences and so there will definitely be a thing or two that you can learn from them.

One of the simplest ways to do that, I’ve come to realize, is to tell people what worked for you without telling them they should do the same thing too. Let them decide what they want to do – whether they want to take the route you did or do something different altogether. At least, by sharing your story, you have armed them with the information they might find useful. Also, seeking advice can be your greatest learning experience. We are surrounded by really smart people who have knowledge and experiences that we don’t have. Why not reach out them sometime and pick their brains? This takes humility and trust. Granted you might not always get what you were looking for but everyone has had unique experiences and so there will definitely be a thing or two that you can learn from them.

I have come to realize that advice gets a bad rep because it’s usually unsolicited and often times forced upon the receiver. There might be no ill will involved but the manner in which it is dished out makes you believe the contrary is true. I have also learnt that the presumption of expertise is a natural tendency. We like to think we know things and have good control over all situations in our life. And it is that overconfidence that pours out in the form of advice, and it almost always sounds like a boring sermon that you can’t wait to get away from.

A psychology paper published earlier this year, found a compelling explanation as to why advice can sometimes be irksome. It’s because giving advice doesn’t only benefit the recipient. It also makes the advice-dispenser feel powerful as well. Though giving advice can seem (and in fact be) generous and kindly, it also creates a power imbalance of sorts. Underneath the exchange is the subtle suggestion that the person receiving the council needs something from the advice giver.

These days when someone asks me for advice I first ask myself if I have experience with a similar problem. If the answer is no, then in that case I mostly direct the advice-seeker to someone else. And in instances when I feel like I have to speak up and say something because ‘I Know’, I usually chew the insides of my cheek and refrain from it. Because, no matter how it’s couched, it’s wise to resist giving advice, especially if unasked for. There is no two ways about it. A friend recently said, “Be careful whose advice you buy, but be patient with those who supply it.” And with a family get together looming over me, it seems I will heed that advice.