I’ll answer the second part of your question first. Yes, a recent circular from Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) requires banks to invest 10% of their loan book to energy and agro sectors. [break]

Loans advanced by commercial banks currently aggregate more than Rs. 550 billion. My estimate of the currently outstanding loans here is less than Rs. 25 billion, the majority of which is to finance hydropower production. So a lot of bank finance may be available for agriculture in the coming days.

Energy and agriculture being two prominent areas where our country has apparent comparative advantages, NRB’s move is very well intentioned. These sectors, along with tourism, are more likely to lead to sustainable economic growths.

However, I personally have apprehensions over any form of directed lending, especially given the fact that we’re an over-banked economy. Competition among banks is stiff enough to push them to find viable investment opportunities. We need to guard against excessive money supply into specific sectors, thus creating gluts and possibilities of diversion of funds.

We’re in the middle of a trying situation in the real estate sector; we certainly wouldn’t want to create another asset bubble.

Moreover, money isn’t the only ingredient necessary for a business to succeed. Generally speaking, I believe money is the least of our worries right now: there are several other impediments to economic growth in our country. Acute power shortage, political uncertainty, poor road infrastructure are a few of the major hurdles.

That brings me to the first part of the question. There are a number of challenges associated with our agro sector. Economies of scale, technology, storage facilities are a few of them. Besides, meaningful crop insurance – to cover the worst-case scenario – isn’t yet available in Nepal. These apply to poultry, horticulture and fishery as well.

But I’m not discouraging you from approaching a bank: Not at all! Agriculture has to develop in a big way, and it won’t if we hide behind problems all the time. Banks will consider your request if you’re able to present them with mitigations for risks discussed above. For example, lack of crop insurance can perhaps be mitigated by a pledge of revenues from your other sources.

You’ll appreciate, though, that banks aren’t venture capital funds, and their risk appetite is usually less than that of entrepreneurs or a private moneylenders. Banks will seek to ensure that their loans are reasonably bankable in order to safeguard the interests of their depositors.

I want to sell my ancestral property at New Road and buy a small house somewhere else in the city while keeping the rest of the money in a bank so that my mother has her own source of income to run the household. My father disagrees with this idea, saying we must hold on some more. Please advice.

P.S.: My father will be reading this column; so please be persuasive.

I get an impression that your father isn’t averse to selling the property but wishes to hold on a bit, perhaps in anticipation of a better price. Property prices go through cycles, and I’m afraid the present time is the wrong end of the cycle and the prices are likely to remain subdued for several more months.

But one can also argue that New Road is a prime location and therefore not affected by price cycles. Even so, property market generally is likely to remain bearish in the near term.

My advice to you, purely from the financial point of view, is that you should sell only if you can get a good price and (not or) if you can use the sales proceeds to improve your future cash flows so that you can eventually increase your wealth.

Also remember that bank deposits may not fetch relatively high returns as it did in the past two years. Unless you’re in a cash bind, you generally wouldn’t dispose of a prime property just to meet family expenses.

Is it not uncommon for FIs (financial institutions) to paint a nice picture even when their financial status isn’t as sound? Is this really the case? How can we tell by looking at the balance sheet as to how an FI is doing?

At the very outset, let me assure you that a good bank won’t manipulate its financial statements. The Central Bank enforces standards on assets and income recognition, and banks have to abide by them. Good banks actually exceed the standards sometimes and adopt more conservative global best practices.

However, the sudden failure of a number of FIs creates some doubt about published financial results. I would attribute this largely to issuance of too many licenses without commensurate enhancement in supervisory capability, coupled with poor market conditions triggered mainly by the political mess we are in. That said, FIs shouldn’t use weak supervision as an excuse for their own governance failures. Sensitivity of banking business dictates that they self-regulate.

You should study an FI’s balance sheet over a period of time to pick signs of dishonest financial reporting. Probable signals are: erratic movement in profits, disproportionate growth in business relative to market conditions, inadequate loan loss provisioning, significant unexplained variance between provisional and audited accounts, etc. Non-financial information should also be analyzed to see if they are in sync with the numbers published. For example, look for number and frequency of auction notices of an FI and see if they appear reasonable relative to their published NPA level.

In a competitive market, lack of transparency and unreliable reporting by an FI automatically leads to greater uncertainty and lower efficiency. Customers then respond by taking their business elsewhere, investors respond by offloading their holdings.

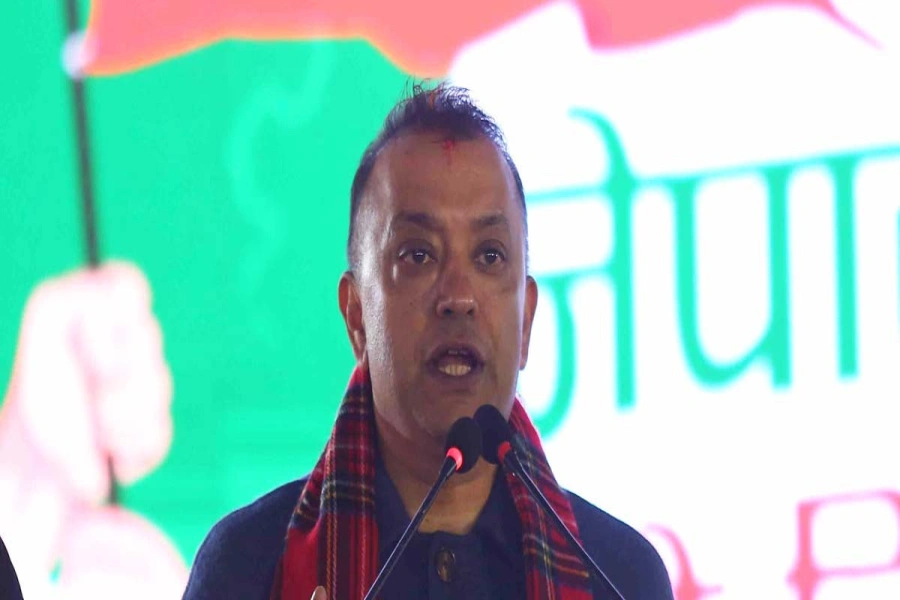

Joshi is the CEO of Laxmi Bank

Moneywise: Ask Suman Joshi