It all began after the gathering. Until then, I’d never had cause to question even what I was. It was as if we all had a common, immutable destiny that consisted merely of living day to day until we died. If there was vague fear attached to the idea of when death would come, no one brought it up. At least it would be quick, that much we knew.[break]

I did wonder why, just once, right after we found out what was going to happen to us. There’s always the first time you look up from your fun in the sun and see death, and nothing else needs explaining. But I didn’t quite understand why it had to be so, even if my brothers, after gazing dully at the scene for a few seconds, started up a game of jump-the-highest.

Confused as I was, it was good hanging out with my brothers all day. Always a new game to play, and once we tired of that, always something to nibble on. Those were the good days. So good, in fact, that perhaps they were meant to compensate for the brutality of the end.

When they came to take our two stepbrothers away – they were already strapping lads by the time I was jumping about the yard – twin holes were punched into the fabric of our lives. It happened one ordinary afternoon as we were all snoozing in the sun, tired out from the morning’s play. For some reason, our stepbrothers were nervous, restless. They just couldn’t sit still, and they were well past the age of jumping about.

When the men came, they simply allowed themselves to be led away. My brothers followed, perhaps thinking it was the beginning of a new adventure – everything was an adventure for those addle-headed kids – but only got a few kicks for their trouble. One of our stepbrothers looked back as he was dragged around the corner of the house. There was nothing to see; his eyes were empty, and that told me all I needed to know. Soon our turn would come.

And life went on as usual, until the day Father came back. He wasn’t really Father, or not anymore. But you can bet everyone was looking, especially Mother, who had just had another batch of kids.

By now we were almost full-grown, me and my brothers. We must’ve fancied ourselves pretty tough, too, for when Father (or someone like him) walked in that day, we wanted to prove ourselves. Because he was so…impressive. Yes, he was dirty and ragged and long-haired and smelly, but he was magnificent exactly because of that. He looked and acted like he owned the place, and we felt like effeminate pretenders before his swaggering, overpowering presence. Undeniably he was from the Street, and before us, he was a King.

He walked straight into the yard. Turning away contemptuously from us, he came up to Mother and circled her, snuffling and snorting in the most peculiar way. God knows what he was trying to do. Mother didn’t do anything, but she seemed disturbed, and even…excited? It was all very strange. Then the Old Man appeared at the other end of the yard and, apparently enraged, flung a rock at the intruder. Thud! If it hurt, the Street King didn’t show it. He simply lowered his head and, dignified as anything, stalked off.

But not before I stepped in his way. I guess I wanted to see if I could measure up to him.

An almighty whack on the side of my head floored me. I sprawled in the dust, and he stood over me, almost straddling me. As I stared up at the thick beastliness of him, he snorted triumphantly. Then, with one last look at Mother, he left. My brothers loomed over me, half scornful, half pitying. But finally I knew why we would never be like the Street King. Neither men nor women, we were doomed to end as we had begun. I couldn’t remember how it had happened to me, but I had seen it done to the younger kids. Now I knew what it meant.

Too soon, the day of leaving arrived. This time, no one came to look us over. The Old Man kicked us awake, roughly trussed the three of us together, and without preamble dragged us away from Mother and the yard that was all the world we had known in our short lives: the haystack that waxed and waned with the seasons, the noisy dogs that came and went, the whining children that lived in the house above us. Mother barely even looked our way.

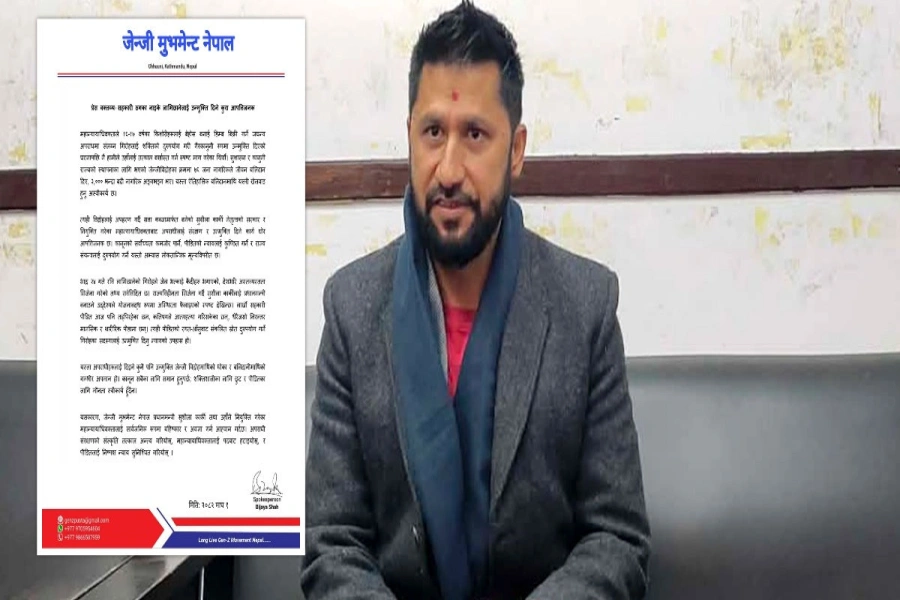

Illustration: Sworup Nhasiju

The air was nippy. I was pensive, dulled to the anticipation of oblivion; the others seemed excited. But there was no mistaking the Old Man’s mood. He whistled a jaunty tune as he pulled us away from the house, to where we’d never been before. Stumbling along a narrow path that suddenly widened to a clearing, we came to where a huge creature lay growling ferociously. We baulked – this was much bigger than the smelly growlers the people sometimes rode into the yard – but the Old Man lifted us up to a grinning boy riding on the creature’s back. Then he jumped on and with a bone-rattling roar, we began moving forward.

The terrible jarring meant we could neither stand nor lie down, but we were kept busy looking at all the other roaring creatures of all shapes and sizes running along a big path lined with trees and houses. My brothers jumped up and down when they saw the Street King, who was nosing through a tempting looking pile of vegetables by the side of the path. For a second, then, I allowed myself to dream that we were just leaving home to be let loose, to become magnificent free spirits like the Street King, who was simply not afraid of people with ready rocks, sticks, and kicks.

There was the world to see, but soon my head began to spin and I lay down on the creature’s cold and dirty back. The Old Man, seated on a rug next to the ever-grinning boy, laughed. The very air around us seemed to grow more frenetic by the minute, but finally we juddered to a stop in the midst of a dust cloud. The Old Man leapt up, rubbing his hands in the morning sun. And then we were lifted off the creature and back onto solid ground, thank heavens.

There were scores of people walking here, there, everywhere, and many more like us being pushed, pulled and lifted on and off the roaring creatures. As we tried to make sense of the scene, my eyes fell upon three of our kind, huddled against a tall metal table a few feet away. On the far side of the table, another was tethered tightly to a wooden post. So tight, in fact, that his head was rammed against the post. A scruffy man with a hairy belly barely covered by a blood-spattered singlet now approached and grabbed the prisoner’s legs, holding him tight. Another man then unsheathed a wickedly curved knife, raised it high above his head and whooosh!!! In a second all that remained was a kicking body spurting blood, and the head, still tied to the post, tongue out, lifeless.

This time, my brothers were watching, too. Had we forgotten in the dusty play of our halcyon days? If it hadn’t been quite so obvious to them exactly what had happened back then – a commotion, uncle standing there bleating, then lying on the ground in two pieces – it was crystal clear now. The body was flung unceremoniously into a great tub of hot water, and immediately a boy began tearing off great hunks of hair. The suddenness with which the white skin was exposed made me go cold. The hairy-bellied man unfastened the dead head from the post, placed it ceremoniously on the table, and moved towards the group of three shivering there. They shrank from him.

It was a smack in the face for the Street King. The cold fingers of fate – albeit in a hot water tub – awaited.

Before we had time to reflect, however, the Old Man appeared and dragged us through the crowd, and soon we were surrounded by hundreds, no, thousands, of our own kind. We weren’t together for much longer. Despite making a great show of admiring us in front of the men and women who came to look, the Old Man seemed glad to be rid of us. It was so terrifying to be in that din of shouting and bleating and killing that I was actually relieved when rough hands led me away. This is the end, I thought helplessly. But I was once more lifted onto one of the growling creatures and off we went, bumping up and down until it was dark. I was lifted down and tied up again. A man brought me a whole pile of good fresh grass and leaves, patted me on the rump, and left. For the first time in my life, I was alone.

I was still alone when I awoke. There was another stack of fresh food next to me. I was tied to the side of a huge building, quite unlike the small, shabby roof I’d grown up under. In front of me stretched an expanse of grass. I could see houses in the distance on both sides.

When the sun was going down, a couple of men came to look at me, and left me more food. The same thing happened the next day, and the next. I had no idea what was going on, but who was I to complain?

Then one evening, just as I had begun to wonder whether I hadn’t been quite wrong about my destiny, they came to get me. Laughing, they led me into the building, and then carried me up, up, up, onto another ground. Here, many more people were milling about, eating, drinking, and shouting. My arrival seemed to fill them with excitement, but I was only tied up in a corner. From time to time, the people would come over in ones and twos. They looked me up and down, their faces gaunt in the white lights. Invariably they laughed before walking away.

Then, there was a frisson of anticipation. A fat man called out in a very loud voice, and all the rest fell silent. He pointed to a bucket he was holding, and they laughed and cheered. A woman came out of the crowd, reached into the bucket, and pulled out a small white piece of paper. The loud man took it from her and shook his head, smiling. He called out again, and another came forward and took out a piece of paper. But he, too, returned to the crowd. And so it went, on and on. Only a skinny woman with sad eyes refused to come forward; everyone laughed and looked at me.

Finally, amidst a growing clamor, the loud man himself reached into the bucket and pulled out a piece of paper. He paused, the corners of his mouth turned down, and he shook his head. A ragged cheer went up. The man tilted the bucket to show it to the crowd. Just a few pieces remained, and now he began to pick each one out, a puzzled look on his face. Suddenly he went “Ah!” The skinny woman ran up to him, her eyes fierce, and snatched the paper away. Her face lit up, and she ran straight over to me and hugged me. More laughter. I was bewildered: she was holding out the paper to me, and on it was drawn the head of a goat. I nibbled on it as she stroked my head.

That night, I was taken back down to my space, where I fell into a deep sleep. I’ve been down here ever since, I can’t even remember how long. During the day, they let me graze across the length and breadth of the unending field, a long, long rope ensuring I don’t stray too far. At night, they reel me in. And so on, day after day after day.

I don’t know what’s going on, but it seems to me I’ve missed my date with destiny. If that was to have my head chopped off, my hair ripped out, and be cut up into little bits, perhaps you would consider me lucky. To be honest, I’m not sure this is very much better. The expanse of the field defeats me; the emptiness of my days bores me to tears. There’s nothing to look forward to, at least nothing that I can see. From time to time the skinny woman comes and pats me on the head, and I try to tell her that if she saved me, it shouldn’t have been for this. But she doesn’t understand.

When I was young, Mother told us of the goats who live up north. Instead of spending their lives jumping about in the sun, they walk for weeks across the cold mountains, carrying salt on their backs for their masters. It’s a tough life, to be sure, but these are tough buggers who are proud to be working for their keep. And there’s nothing like the fresh air of the north, Mother said, and the views of the sparkling mountains reaching up to heaven. The plants grow juicy along the mountain paths, too many kinds to count, and best of all is the sticky herb the men call ganja and the goats call ghaas. They are so surefooted, these goats, that the men let them munch on this sacred herb wherever they can find it. In the rain and the mud and the chill of the trail, when the sacks of salt weigh them down into the ground and the ropes cut into their backs, the ghaas closes down their pain, and opens up their eyes.

One day, perhaps, they will come and take me away again. I know where I want to be going.

Rabi Thapa is the author of the short story collection ‘Nothing to Declare.’ The author’s portrait is by Sworup Ranjit.

Where people sell grass to pay for toilet