Context

The use of cannabis is on the rise in Nepal and has been a matter of concern for those working in areas of crime investigation and public health. While there have been increasing debates about cannabis production and sales legalisation, including Nepal’s parliament, we feel the need to inform the general public and policy makers so as to enable informed decision on the issue.

According to the 2018 World Drug Report, cannabis is the world’s most widely used illicit substance, with 192 million people using it in 2017 and 151 countries reporting its seizure. Cannabis users continue to rise worldwide whereas similar data is not available from Nepal. Nepal’s last hard drugs users’ survey was conducted in 2012/13 which reported 90.5% respondents ever using cannabis as opposed to opiates (93.5%); of these, 87% users preferred to use cannabis. Overall, 91,534 drug addicts were reported which nearly doubled in the seven years.

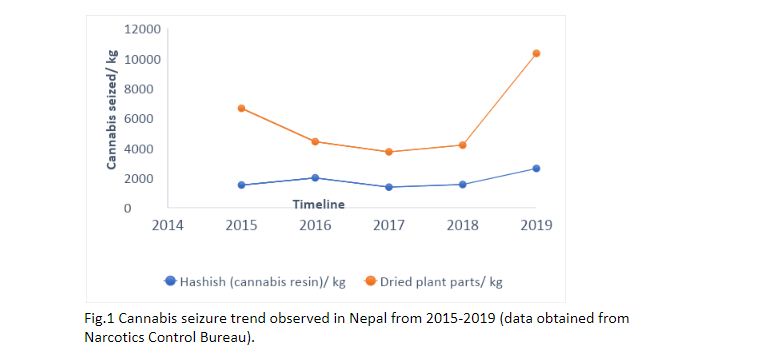

Drug use was highest among young adults (53% drugs users up to 24 years). In 2019, the National Forensic Science Laboratory reported 9.6% cannabis cases out of 615 narcotics cases analysed, which showed an increase of 69% over the period of four years. Similarly, Nepal’s Narcotic Control Bureau in the same year seized 2,622 kg Hashish (cannabis resin) and more than 10,320 kg of cannabis (dried plant parts, see Fig.1). 4,683 tonnes of cannabis herb and 1,631 tonnes of resin were seized worldwide in 2018.

Legalisation and decriminalisation trend in other countries

Thailand rushes to rein in cannabis use a week after decriminal...

In 1996, California became the first US state to legalise cannabis for medicinal purposes under supervision. Since then, many other countries have either legalised or started debating on the legalisation process. Approaches taken by countries vary, some countries have defined exact quantities of cannabis that people are allowed to grow for personal use whereas others have taken a more generic approach. Uruguay became the first country in 2013 to legalise cannabis and their approach is worth mentioning here. They established a government-controlled cannabis market and also allowed registered home growing and communal growing (i.e. social club). Since 2017, buying state-grown cannabis from pharmacies has been allowed. Similarly, Canada legalised cannabis for recreational, medical and research purposes in 2018. Thailand is the first Southeast Asian country to legalise cannabis on medical grounds. A combination of regulatory approaches have been used: (i) taxation and commercial supply via licensing; (ii) government control; (iii) allowing small amounts for home grown cannabis (no tax, no sales); and (iv) collective growing and use of cannabis as social clubs (no tax, no sales).

The debate on legalisation and decriminalisation on cannabis use and sale has also increased in many other countries, such as in the UK and Nepal. Decriminalisation refers to the removal of criminal status whereas legalisation refers to making an act lawful that was previously prohibited. The current debate in Nepal’s parliament mainly relates to the legalisation of cannabis. Similar systems are already in place in Alaska, Colorado, Oregon and Washington, and in Canada, Uruguay.

Use of cannabis and current status

While cannabis is generally perceived as a drug of abuse, it has multiple uses. In Nepal, Ayurvedic physicians have used cannabis based medications to treat irritable bowel syndrome, dry cough, diarrhea, dysentery, depression and anxiety etc. Its therapeutic importance in Ayurveda has been well recognised; 29 pharmacological properties and actions, with 13 dosage forms to treat more than 29 medical conditions have been reported. Cannabis based products are also available as medicines in Europe, for example, Sativex, Marinol and Cesamet to treat cancer, AIDS and multiple sclerosis.

Cannabis used for recreational purposes is available as compressed dried plant parts, resin and oil (fig.2). It can be smoked, eaten (mixed with food/drinks) and vaped. Cannabis also has industrial use in manufacturing of hemp, bioplastics and biofuel. It is legal to cultivate and supply cannabis plants for hemp fiber in Europe using the certified seeds (with low levels of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol or THC). In Nepal, only wild cannabis can be processed and used as medicine or as an industrial product.

The 1976 Narcotics Drugs Act of Nepal classifies cannabis as one of the narcotic drugs that is controlled in the country (excluding wild cannabis). Accordingly, any plant of Cannabis genus is controlled. Second amendment to the act included prohibitions in various aspects of cannabis, including cultivation, production, preparation, purchase, sale, distribution, export and import, storage, trafficking, and consumption at an individual level. However, the production of Hashish or Charas (i.e. cannabis resin) from wild cannabis grown in western hilly region of Nepal is not controlled. This then raises questions: What are the criteria used to confirm wild vs cultivated cannabis? What about the level of THC present in the wild cannabis? What is happening with the Hashish that is produced from so called wild cannabis? All these are issues that need a special consideration and it is now time to reflect and revisit our Drugs Act to modernise and clarify some of the issues highlighted here.

Generally, a cannabis plant is controlled when it has a usable amount of THC present. But, in some counties including Nepal, all strains or varieties of genus cannabis (even with negligible amount of THC) are controlled. It is useful to note that cannabis plants have more than 400 chemicals and 80 cannabinoids have been identified already. Out of these, THC and CBD (cannabidiol) have opposite effects. THC is a major psychoactive (i.e. mood altering) compound present in cannabis whereas CBD is antipsychotic in nature. Most of the THC content in cannabis plants resides in female flowers and trichomes (hairy structure) which can reach to 20% or more THC content.

Current debate on cannabis legalisation

There are several issues to discuss before debating on legalisation of cannabis in Nepal. We first need to discuss the positives and negatives of cannabis cultivation, rules and regulations to follow after legalisation, its quality control (like THC content in plant, seed variety), processing, transportation, sell and distribution (i.e. manufacturing to distribution network) and then control and monitoring processes (e.g. licensing). Among others, our prime focus needs to be centered on: (i) public health; (ii) crime reduction; (iii) protection of vulnerable groups from drug misuse and exploitation; and (iv) securing good value for money by ensuring quality products. All of these can only be achieved if we balance between business motives and public health centered approach. As other countries are also proposing similar changes or have already implemented cannabis legalisation, it is good to form a network of domestic and international experts and take their feedback on reforming cannabis policy.

This might be the right time to lobby for a pragmatic reform rather than taking a prohibitionist approach on cannabis debate. Hence, we recommend hosting a series of multi-stakeholder dialogues where experts from drug policy and administration, legal representatives, agriculture, environmental science, monitoring and evaluation team, public health, Narcotics Control Bureau representatives, representatives from forensic science lab, policy makers and media professionals are involved in the discussion and consultation process. Great ideas have not succeeded well in the past due to lack of proper consultations or limited monitoring and evaluation process; this should be factored in from the beginning. All of these activities must also be complemented by prevention and education measures aimed at reducing drug related harm which can be achieved by working in collaboration with education authorities, members of public and police partnerships.

Gautam principal lecturer in Forensic Science (with research focus on drugs and analytical chemistry), Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK. Email: Lata.Gautam@anglia.ac.uk

Satyal is a consultant Ayurveda physician, Annapurna Neurological Institute and Allied Sciences & Naradevi Hospital, Kathmandu

Bohara is a researcher on drugs policy in Nepal, DSP of Nepal Police, Police Headquarters, Kathmandu