The once-powerful chairperson of the royal-military regime claims that some politicos had promised to protect the Shah throne. He has not named names. It is possible that some stalwarts of Nepali Congress and CPN (UML) indeed swore allegiance to the Crown. [break]

Up until the last settlement, Madhav Kumar Nepal was writing notes of dissent to urge a referendum to decide the future of monarchy. Kamal Thapa has since appropriated his political position. Nepal lost elections from two constituencies. Thapa forfeited his deposits in the electoral fray.

The mandate of the Constituent Assembly was unambiguously republican. That could have been the reason the last Shah surrendered the crown and vacated the palace without publicly mentioning anything about his supposed understanding with the politicos of what was known back then as the Seven Party Alliance (SPA).

If indeed there are some written commitments—there is no telling what Nepali politicos would do under duress—they are not worth even the paper they have been scribbled upon. Gyanendra, however, has reasons to think that the direction of the wind has turned in his favor.

The national polity is caught in the quicksand of its own creation. The Interim Constitution is intact, but its institutions and instruments failed to understand the limitations of a provisional statute. The legislature fell short of delivering desired results on schedule.

The executive did not have the courage and creativity to design practical alternatives. The judiciary set the final date of expiry of the Constituent Assembly’s extended term without foreseeing the consequences of their learned interpretations. Since everyone thought that defending the letter and spirit of the Constitution, as well as intentions of People’s

Uprising, was its sole prerogative, the CA sank under the collective weight of those sitting upon it to keep a close watch.

The society stands deeply divided between mono-ethnic schemers committed to the unitary character of the state, and multicultural radicals advocating identity-based provinces.

The call of Janjati leaders to socially boycott anti-federal forces has not yet found traction. However, there is no telling what direction such hardening of positions will take in the coming days.

The mono-ethnic majority castes—Hindu and Nepali-speaking protectors of proud Gorkhali legacy—is happy that an inheritor of history has chosen to wage ideological battles against ideas of secularism, inclusion and federalism. However, some members of externalized and marginalized communities too have begun to fear their own hard-earned freedom.

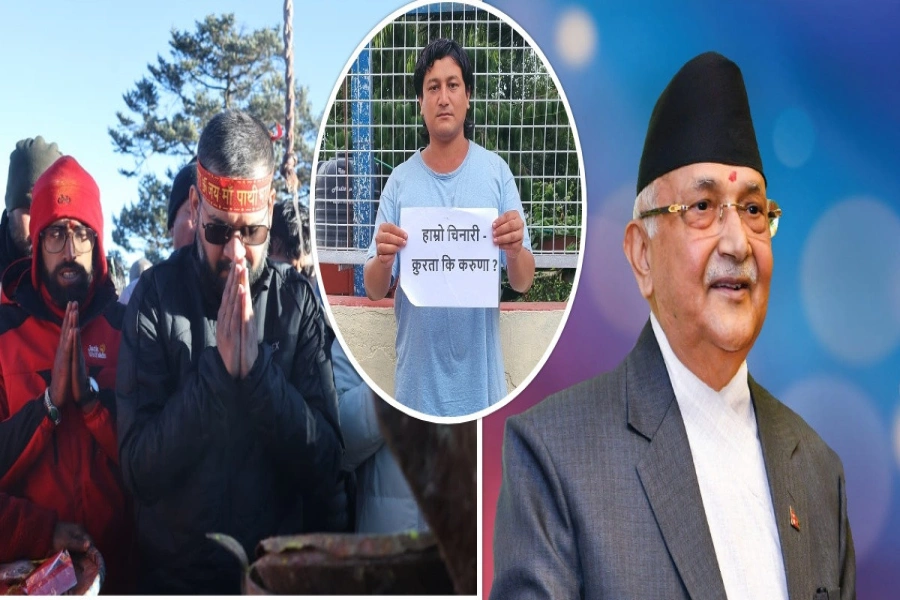

Voices of dismissal in the public domain notwithstanding, people from the plains to the mountains seem to have given Gyanedra’s grievances a patient hearing.

There could be many reasons behind people’s curiosity towards outpourings of the ousted monarch. Firstly, public memory is phenomenally short and few, other than those directly affected, now remember the excesses of the royal-military regime. Secondly, he is no longer considered a credible challenge to the republican order.

Thirdly, he has begun to sound regretful, even though not yet apologetic and nothing entices social compassion as strongly as remorse of a fallen strongman. Fourthly, showing sympathy towards the former king is a potent way of expressing discontentment with the existing socio-political fluidity.

All these reasons are rather harmless. What raises the alarm bells is the possibility of a former ruler fancying himself as a guardian angel from a glorious past and restorer of the old order.

British historian Ian Kershaw, one of the world’s leading experts on Nazi Germany, points out the moving force behind the rise of Nazism: “What, in the changed conditions after the war [WWI], Hitler was able most signally to exploit was the belief that pluralism was somehow unnatural or unhealthy in a society, that it was a sign of weakness, and that internal division and disharmony could be suppressed and eliminated, to be replaced by the unity of a national community.”

Illustration: Sworup Nhasiju

Fear and loathing

Patriotism is love of one’s country and the willingness to sacrifice for the betterment of society. Even patriotism, when combined with self-righteousness, can degenerate into what Samuel Johnson called “the last refuge of the scoundrel.”

Sentiments that redeem patriotism and make it human are commitments to values of political equality, social justice, economic fairness and cultural plurality. A patriot takes pride in human achievements and has enough confidence in the country to tolerate dissent.

Since criticism is the primary method of recognizing weaknesses and inspiring contemplation for social regeneration, patriots do not shy away from the severest censures of established practices. Patriotism is grounded in practicality and nationality.

Nationalism, on the other hand, is such a lofty notion that it does not need ground beneath its feet to stand upon. Predating

history, nationalism sources itself to myths, symbols and legends that have bestowed special qualities and purity upon people of destiny. Unlike nationality, nationalism does not create a relationship of rights, duties and obligations between the state-nation and its citizens.

What nationalism does instead is recognize the “self” and ostracize everyone else as the inimical “other.” Thereafter, one’s nation is destined for greatness. In case something goes wrong, it must be the fault of “outsiders” masquerading as “insiders.”

Without commitment to homogeneity, the idea of nationalism falls flat. That could be the reason no true nationalist can triumph without identifying a real or imagined “traitor.” Contempt for minorities and disdain for cultures perceived or portrayed as alien are essential elements of nationalism. It has been said that the Nazis did not have to invent hatred for the Jews, Communists and Gypsies. They merely harvested fear and loathing afflicting the defeated German society.

Ever since the Treaty of Sugauli (1815-1816), rulers of Nepal have assiduously cultivated a culture of duality whereby the elite is duty-bound to serve the interests of overlords abroad while proles at home are trained to hate all outsiders.

So Madheshis could not be trusted. All non-Hindus are inherently suspect; but proselytizing faiths need to be feared even more. Homogenization of culture is necessary, and manufacturing uniformity is essential to build unity out of diversities.

All these values have become so ingrained that questioning their relevance is interpreted as treachery. Political concepts of secularism, federalism, and inclusion not only questions the established values of so-called “unity in diversity” but seeks to establish alternative set of ideas to respect diversities within unity. Ergo, fear of fragmentation permeates the polluted Kathmandu air. The strengths of Gyanendra’s ideas lie precisely in their staleness.

Afraid of freshness, some may flock to the familiar smell of rotting feudalism. The respite would not last, but it can disrupt the formation a forward-looking state-nation where people would be proud of achievements of the Revolution of 1950, People’s Movement of 1990, the Rhododendron Revolution of 2006, and the Madhesh Uprisings of 2007 rather than vacuous claims bereft of human endeavors, such as “Mount Everest is in Nepal” or “Buddha was born in Nepal.”

Longings of the alienated

More perplexing is the desire even among a section of the marginalized to look longingly towards the certainties of the past. Apparently, Madheshis, Muslims and Dalits have nothing to gain from the restoration of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal-1990.

It was a charter that aimed to manufacture uniformity under “one language, one dress, and one people” formula. The constitution was slightly less severe towards other religions, but its preferences for beliefs of the majority were unmistakable.

Erich Fromm, a leading theorist of the Frankfurt School, explains the mechanisms for escape from the alienation of “freedom.” Through automaton conformity, one changes the self to the preferred type of the society. Consider a Madheshi wrapped in labeda-suruwal and struggling to speak in Nepali with his children to sound nationalistic.

Authoritarianism is giving control of oneself to another. Imagine predicaments of the Janjatis in CPN (UML) who have spent their lifetime in building a political culture where their aspirations of identity and dignity have no place whatsoever.

Then it no longer appears irrational why some ultimately adopt the path of destructiveness, which is a process that attempts to eliminate “others” to escape the crushing burden of freedom.

Fomm’s prescription sounds too intuitive to be scientific, but it continues to be valid after decades of scrutiny: “There is only one possible, productive solution for the relationship of individualized man with the world: his active solidarity with all men and his spontaneous activity, love and work, which unite him again with the world, not by primary ties but as a free and independent individual”

The confidence to build such solidarity comes from pride in one’s primary identity and not its denial under pressure of conforming to established notions of “nationalism.”

By harping too much on the glories of the past and symbols of Gorkhali identity, Gyanendra may unwittingly be undermining the very cause that he seeks to promote: Longevity of Nepali identity.

The nationality of the future would be based not upon mythical “national community” but a very practical law-based country composed of self-confident “communities of nations” within the nation state.

Lal contributes to The Week with his biweekly column Reflections. He is one of the widely read political analysts in Nepal.

Living with fear