Binod Shahi, president of Snow Yak Foundation, came in the top 50 out of 37,000 teachers in the Global Teacher Prize 2018. Shahi was recognized for his immense contribution in providing education to children of Dolpa, a part of Karnali Pradesh in Nepal.

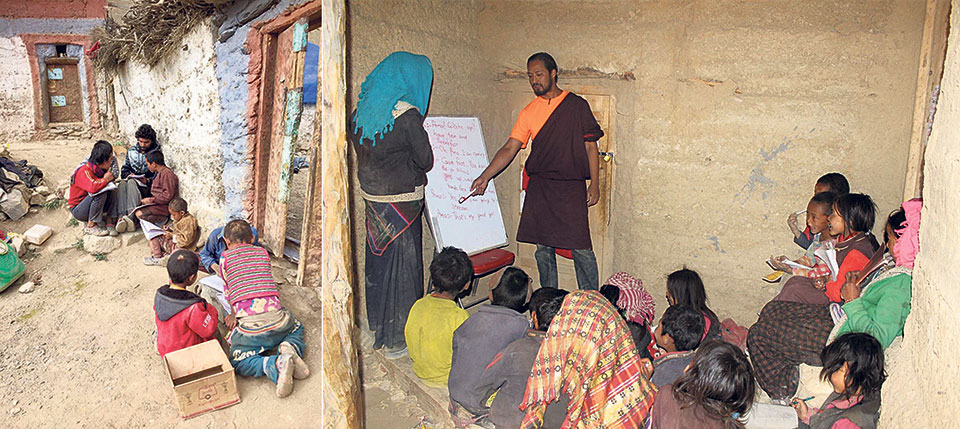

In 2011, Shahi’s foundation started a six-month fellowship through which youths could go to Dolpa and teach children there. And it’s through the fellowship that many interested individuals, from different fields, have gone to Dolpa to give children there are a chance to learn.

“It wasn’t about trying to change Dolpa by efforts from the outside. What we actually wanted to do was make Dolpa independent by training the locals there to become teachers themselves,” says Shahi explaining that they chose Dolpa because of its remoteness and lack of access to education.

Shahi himself has spent a lot time in Dolpa and he has experienced the local’s difficulties first hand. Life, he says, is extremely difficult in Dolpa as there is a lot of scarcity there. He laments that people there still die from simple conditions like fever and jaundice.

“Lack of facilities like pharmacies and hospitals is one thing, but the people there aren’t even aware about basic hygiene and live in sad conditions,” he says further adding that political leaders do next to nothing to better the situation there.

The locals have taken to calling him “Sir of the Himalayas” in appreciation of his efforts to bring about change.

A dream shared by Dolpa people will come true after 500 meters

Shahi mentions that the fellowship is mostly open to youths as they are the future of the country. It is through them that a new Nepal is possible. “And for that they have to see the condition of remote places of Nepal,” he says.

“We have provided teachers in 12 schools but we need the involvement of more youths. Currently, there is one teacher for 60 students,” he says adding that they work with a limited budget as they don’t take foreign donations.

Sushma Shakya, a former fellow, recalls teaching children with the help of songs as they seemed to be able to memorize it. “I went to Dolpa when I was 23 years old because I was studying social work and the fellowship aligned with my choice of subject,” she says. Shakya was stationed at Chala village in Lower Dolpa.

At the village, everybody believed in the God Chala and all their activities were decided by this divine power. The god was believed to reside in a human and thus some children were considered to be holy. The chhaupadi pratha also pose a real challenge in Dolpa, she says, as many women still observe it despite it being banned elsewhere in the country.

Binita Jirel was assigned to teach Nepali in Nyisal village in Upper Dolpa. “It wasn’t the chhaupadi pratha or the superstitions that were the challenge here for me but the lack of roads was a real problem. I had to walk for eight days just to reach the school,” she says. Jirel adds that there weren’t many teachers and that communication was often difficult because people there spoke a different dialect of Nepali.

However, Jirel adds despite its geographical remoteness and lack of awareness about different matters, she found the people of Dolpa to be quite liberal in their thinking. “A man wouldn’t hesitate to approach a single mother for marriage. That kind of attitude is still frowned upon in many parts of the country, even in Kathmandu,” she says.

Kumar Gautam, on the other hand, says that life is still challenging in Dolpa. Gautam, who went to Dolpa when he was 24 years old, says inexperience can make things even more challenging. “As it is, teaching is tough and it’s tougher when the children can’t grasp the basics – like say what a computer is – because they have grown up in conditions very different to that of children elsewhere,” he says.

What Gautam found to be even more alarming was the fact that many people in Dolpa would risk their lives for Yarsagumba. The caterpillar fungus was a source of livelihood for many families and since these were found in high altitudes, many people lost their lives or injured themselves while searching for it.

Hrishav Bhattarai, a computer engineer by profession who had also gone to Dolpa as a part of the fellowship, agrees that the main challenge of life in Dolpa is definitely the remote location and the hardships that come with it. Riding a horse, Bhattarai mentions, isn’t as romantic as they make it out to be in movies. “It’s quite a difficult task especially when the terrain isn’t good,” he says. However, he mentions that life for teachers is easier than for the rest because the people of Dolpa have immense respect for them and Bhattarai recalls his students and their families helping him out in whatever way they could.

“I made the children memorize my phone number to teach them that it has 10 numbers in it. When I returned from the fellowship, the children called me to say they were missing me. It was so heartwarming,” he says.

All the fellows The Week spoke to say that despite the many challenges, teaching children in Dolpa has been, by far, the most rewarding experience of their lives. All that they learnt during the fellowship has changed their perception of things for the better. They believe connecting with them also changed the mindsets of the locals.

“When the local women saw women teachers, they were inspired to get an education, in whatever form possible,” says Gautam adding that it was a give and take relationship in many ways.

Apart from the fellowship, the Snow Yak Foundation is actually looking for other ways to help the children.

“We are actually searching for funding for these children. They will need a lot of support to be able to lead good, fulfilling lives,” says Bhattarai adding that they are taking donations in the form of clothes, shoes, and books to start with. “Any kind of help is welcome,” he says.

(Situ Manandhar)