With the onset of the dry season, Nepal's forests undergo a transition from carbon sinks to carbon sources, emitting significant amounts of carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas. Recent forest fire tragedies, like the devastating blaze in Dolpa district claiming six lives, including three soldiers from the Nepal Army and three children, underscore the gravity of the situation. Inhaling the dense, dark smoke, where Air Quality Index (AQI) levels frequently exceed dangerous thresholds, exposes us to various health hazards. These risks include respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses, significantly affecting individuals' mental and psychological well-being.

In Nepal, narratives on forest fires generally revolve around the Forest Fire Detection and Monitoring System and have yielded substantial advancement by recording real time data on fire events and damage coverage. However, the lack of prompt response to these detections remains one of the key issues. Rakesh Karna, president of the Nepal Foresters Association, has emphasized the necessity of adopting modern technology and declaring a crisis to effectively control forest fires. Additionally, Madan Mohan Shandilya, Divisional Forest Officer at Gorkha Forest Conservation, stresses the importance of proactive measures against forest fires. He highlights the significant challenges associated with disseminating timely messages from the live monitoring department to forest officials, as well as the scarcity of equipment and technical manpower, both of which severely impede firefighting efforts after ignition.

Forests are a means for country's prosperity: Minister Mahato

The Government of Nepal (GoN), in collaboration with provincial governments and local units, has largely overlooked forest fire management, dedicating a paltry fraction—less than 0.5 percent—of the forestry sector budget to this crucial endeavor. As flames continue to spread unchecked, the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA) finds itself ill-prepared and underfunded, receiving only a modest budget allocation from the government. But must we rely solely on the government for forest fire management? Among the myriad of over 200 INGOs and 40,000 NGOs entrenched in Nepal, how many directly or indirectly benefit from our forests? Shouldn't they share the burden of mitigating this crisis? These questions persist, begging for urgent answers.

Given Nepal's financial constraints, options such as Firefighting Robots, AI-supported Sensor Networks, drones for Fire Spread Identification, infrared cameras, air blowers, and foam fire suppressors, while effective, raise doubts about economic viability and require highly skilled personnel. Thus, what cost-effective and environmentally-friendly solutions might prove viable in this context? One approach is through sustainable forest management, employing strategies like reducing vegetation, spacing trees, thinning forests, planting fire-resistant trees, and creating fire lines and fire breaks. But what do we do with the forest residue? Amidst this crisis, Professor Krishna Raj Tiwari from the Institute of Forestry highlights the potential of biochar in combating wildfires and fostering sustainable development. Utilizing forest litter and deadwood and converting forest residue into biochar can mitigate fuel loads, thereby reducing wildfire risks. Furthermore, biochar enriches soil health, boosts crop yields, provides a promising solution for clean water provision through water treatment systems, and promotes economic resilience in agriculture-dependent communities. With the community forestry user group structure already in place, this approach holds promise as a solution to combat wildfires.

A comprehensive assessment of forests would identify the areas most susceptible to forest fires, empowering fire management teams to prioritize fuel treatments and mitigation actions for improved forest fuel management. For example, in their study, Dr. Bhogendra Mishra et al. (2023) highlight that the western Terai plain and the Chure area are at a higher risk of forest fire events compared to the middle and high mountains, with a greater concentration of incidents observed in the western part of the country than in the eastern region. Mishra also notes that south-facing areas, receiving more sunlight, become drier and more prone to forest fires than other aspects. Additionally, forest fire occurrence in Nepal follows a highly seasonal pattern, spanning from mid-November to May, as stated by Sundar Sharma, a fire expert from the NDRRMA. Given Nepal's budget constraints, focusing forest fire management efforts on the period from mid-November to May, particularly during the months of March, April, and May, when forest fires peak in Nepal, is crucial for sustainable forest management.

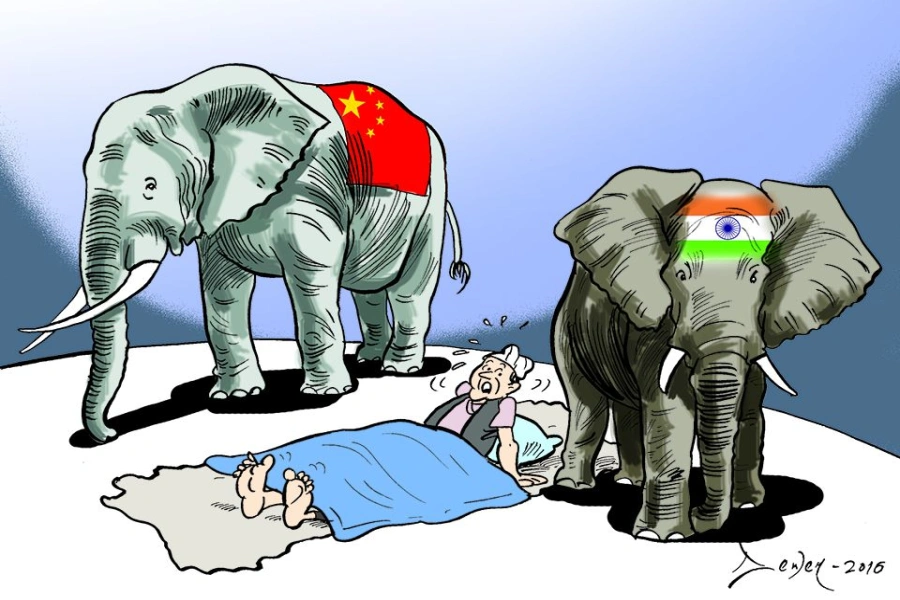

Amidst the tumult of raging wildfires, the anguished pleas of our forests dissipate into the vast wilderness, unheard and disregarded. Just envision the immense potential if a government, armed with access to thousands of forest experts, were to convene and collectively brainstorm solutions to effectively manage forest fires. However, despite this boundless capacity, the government, hindered by the opposition, finds itself ensnared in trivial disputes and inconsequential matters. In this gripping narrative, the urgent call for effective governance reverberates with unparalleled urgency. As the flames of uncertainty continue to engulf our lands, the destiny of Nepal's political factions hangs precariously in the balance. Their legacies teeter on the brink, poised to be defined by the pivotal decisions made in this defining moment.