As a result of never-ending transitions and political instability in Nepal, even after thirty years of the multiparty system and nine years of the present constitution, politics is constantly sliding from democratic norms towards autocratic dynamics, and the economy is on the edge of collapse. Voters are losing faith in political parties and are not optimistic about the future of democracy and the nation's prospects. Untruthful political alliances and syndication for personal and party benefits are responsible for the rising instability, lawlessness, inequality, and mobocracy, leading to the lowest level of public service delivery. Political change has favored only the leaders and their close associates, who have successfully captured important sectors of the state.

Along with some controversial provisions of the present constitution, Proportional Representation (PR) in parliament, based on selection by political leaders, has proven damaging to the political system. The objective behind PR was to support minority representation in parliament, but the selection of PR candidates solely at the mercy of political leadership has ruined the norms of the system, making it difficult for genuine people to get an opportunity. As a result of the PR system, a hung parliament has become a permanent characteristic of the house, and coalition partners, as well as the opposition, easily play the game of toppling and forming governments. Any political party can unite and break up with any other party during government formations, as if there are no principles in Nepal's political parties. Since the promulgation of the constitution in 2015, there have been numerous changes in federal and provincial governments within a few months' intervals. The frequent changes in government have been one of the major causes of instability in Nepal.

There was an expectation among the people after the promulgation of the constitution in 2015 that Nepal would move towards political stability and economic prosperity. But those expectations went in vain as the major political parties and their leaders failed to bring meaningful changes to the lives of the general public. The majority of people are facing severe scarcity for their livelihood, and poverty has forced millions of youths to go abroad. The rule of law is deteriorating day by day, and the nation has always been at the bottom of the world economy. Currently, the country is in such a grave condition that it can't move forward or backward, and now there is widespread frustration among the general public that the nation is heading toward a deep crisis. As the current Constitution of Nepal is a document of compromises among political parties, there are some serious fault lines in it. The constitution partially breaks the norms of people's suffrage and compromises the separation of powers by bestowing exceptional superpowers to the executive and party leaders. The selection of members of parliament by political parties through PR has been, more or less, a part of the flourishing centralization of power by political parties, with the appointment of judges at all levels of courts by a majority of outsiders of the judiciary being an example.

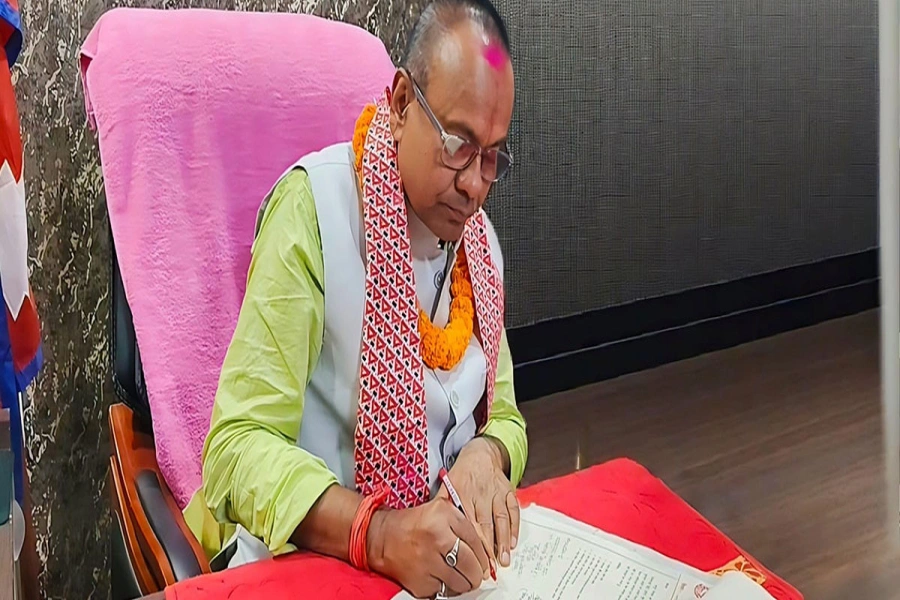

Polls 88 days away, process for proportional representation be...

According to the constitution of Nepal, it has a two-chamber Parliament. The House of Representatives has 275 members elected for a five-year term, 165 from single-seat constituencies, and 110 from a proportional party list. The provincial assembly consists of 440 members from single-seat constituencies and 220 from a proportional party list in seven provinces. The proportional representations in parliament are determined through percentages of different ethnic groups. According to the House of Representatives Members Election Act, 2017, and State Assembly Member Election Act, 2017, 50 percent of women should be selected and nominated in the proportional representation system, and political parties must ensure 33 percent women reservation in the total number of Federal Parliament members, including women from all castes and ethnic groups. Out of 110 seats of PR at the federal level, the act has allocated 31.2 percent reservation for Brahmin-Kshetri (Khas-Arya), 29.7 percent for indigenous people, 15.3 percent for the Madhesi community, 13.8 percent for Dalits, 6.6 percent for Tharus, and 4.4 percent for Muslims.

Proportional representation in local government is slightly different, based on direct election among specific ethnic groups like Dalits, women, and marginalized communities for certain positions. There is no room at the local level for selecting proportional representatives by party leaders, as in federal and provincial parliaments, which has been a major fault line in the electoral system and a cause of frequent changes in government at the federal and provincial levels. Consequently, no single party could bring a majority to form a government under the present electoral system.

We have experienced, multiparty coalitions have been quite fragile, breaking apart due to squabbles between the parties over policy issues, and small parties have been able to determine the composition of the ruling coalition. This undermines the intimate relationship that exists between constituents and representatives in the district. As a result of no single political party holding a majority in parliament, they have been compelled to form coalition governments, often with the support of fringe parties to reach a majority. Such a coalition government cannot carry out coherent policy and produces 'weak' coalition governments rather than 'strong' majority governments, which arguably can lead to indecision, compromise, and even legislative paralysis.

Under the PR system, voters can only vote for entire slates of party candidates, not individual candidates themselves. However, being able to vote for individuals gives voters more direct control over exactly who gets elected. Moreover, sometimes independent candidates cannot stand on the PR list. Those elected via first-past-the-post are regarded as those that ‘belong,’ while those elected via PR are seen as inferior. Fringe parties are often in indecisive positions, possibly leading the government by making large parties their followers. Another accusation against proportional representation is that it could encourage anti-national elements to enter parliament through PR. Because proportional representation makes it easier for small parties to get elected, it also makes it easier for them to run candidates and elect some of them to office.

Many senior party leaders and close associates of top leaders, who do not feel secure in direct elections and fear contesting in a first-past-the-post (FPTP) direct electoral system, are getting high opportunities in PR elections by skipping direct elections. Proportional representation has also been criticized by the general public as an invisible deal for positions in the open market.

An election is like a census of opinion on how the country should be governed, and only if the parliament represents the full diversity of opinion within a country can its decisions be regarded as legitimate. PR was a demand of parties, especially the left parties, to ensure a foothold in politics and preferred economic policies. However, the outcome of the selective PR system in the House of Representatives has not been supportive of a stable government in Nepal. Some experts suggest an appropriate model for PR could be either through direct voting among similar ethnicities for the lower house or through indirect voting for entire slates of party candidates for the upper house.