OR

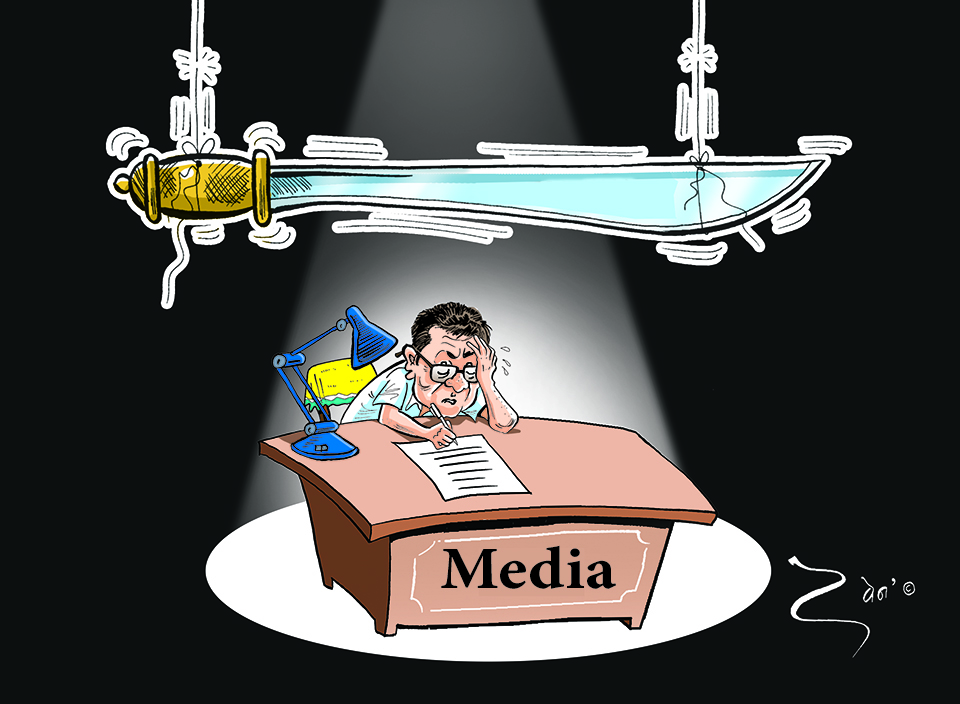

When public figures indulge in media attacks, the prospects and conditions for the media grow dimmer and dangerous by the day

Never have the Nepali news media come under such heavy fire in such frequency in public from both sides of the political divide as they experienced these past few months. Criticisms rained on them and scribes for their coverage and critical comments are insolently intolerant of a sector that is accorded a pride of place in the Preamble of the constitution.

The Federation of Nepalese Journalists (FNJ) and the Press Council remain conspicuous by their deafening silence over the daily verbal battering from political bigwigs that are expected to uphold press freedom. Previously, such attacks used to be termed as attempts at intimidating the press. Even individuals and groups, who the mainstream press habitually quotes as “civil society” leaders or “human rights” experts, choose to feign being deaf and blind to the onslaught.

Freedom Forum, an NGO in Nepal, evaluates the situation as the worst in six years and sharply overtaking the previous year’s record whereas FNJ sees it as a challenging condition.

Political figures rage over any report they wish not revealed. In the past few months, especially broadsheet dailies and TV talk shows carried exposes that put leaders in less than flattering light, based on inconvenient facts and events whose details create discomfort. Hence, government ministers and opposition leaders train their ire on the Fourth Estate.

Battering boy

Ministers fume regularly against the news media when in private conversation with cabinet colleagues but with a tempered—even if labored—pitch if they happen to address public functions or briefings. They register their dissatisfaction with the press people and try moralizing the target of their ire to the full light, sound and audio-range of note-jotting reporters.

In his latest, four-time Prime Minister and Nepali Congress chief Sher Bahadur Deuba accused the KP Oli government of being “not friendly” to the press. The main opposition leader’s comment had less to do with empathy with the media but more to do with lifting the issue as ammunition against the most powerful elected government in Nepal’s history. For, Deuba taunts the press to “criticize me, as you cannot dare criticize the prime minister”.

Former Chief Justice Sushila Karki seethes over what she judges as media bias. More stern was the new Chief Justice Cholendra Shumsher Rana, who on the very day after being sworn in, gave vent to his displeasure. He issued a warning to the press: “It is not the issue pertaining to me personally. The court and judge are an institution. What I saw in the media reports on the court earlier should not recur. You too have a responsibility toward this institution.”

In the wake of a series of stories that dug up how elected representatives misused state funds and misappropriated state-offered allowances, Prime Minister Oli sounded dissatisfied over the media “play-up”. Initial reaction over, realization took the driver’s seat in convincing him about the cancer-like damage inaction would inflict on the credibility of state organs.

Within days after Defense Minister Ishwar Pokharel made a loaded remark asking the press not to engage in disinformation against the government. Oli’s confidant and Chief Minister of Province 5 Shankar Pokharel accused the media of creating public confusion and expressed concern over the “challenge posed by investments made in the media by unseen sources”. Former Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal pontificates mildly on media responsibility.

The cake for the torrent of criticisms goes to Communications and Information Technology Minister Gokul Baskota. Two weeks ago, he gave vent to his rage: “Myths are implanted in news… What is ostensibly attributed to the prime minister finds passage as news without any authoritative source in an entirely another content and context.”

Former Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal the other day called for “freeing journalism from anomalies and discrepancies”. That he and his peers do not bother making matching comments on political parties whose wayward ways have disenchanted the public to a new low is another matter, though.

Media maligned

Last summer, Narayan Kaji Shrestha, of the Maoist faction in the NCP, attributed the delay in unity between UML and Maoist Centre to “leaders who run after newspaper headlines and social media contents”.

In the wake of reports showing ministers and MPs appropriating facilities from multiple sources under similar subject-heads, parliamentarian Gajendra Mahat blamed the media, along with civil servants, for “laying down a trap” against parliamentarians. “For sometime now, reports have publicized that numerous MPs from the Speaker to members of parliament pocket salaries allocated for their personal assistants and motor-vehicle drivers; questionable medical bills are submitted; residential allowances are extracted by those with their own houses [in Kathmandu Valley]; and honorable ministers are portrayed as illiterate.”

In the bad old days of the party-less Panchayat polity, information-leakers were shunned. Today, whistle blowers are accorded respect for contributing to public information. At least the public is informed about what grievances others among themselves have and share with them for or against state institutions and individuals elected to represent them.

Castigating the media is no new phenomenon. In the early years after the 1951 dawn of democracy, too, the debuting private sector newspapers came in for heavy attacks from politicians whose misdemeanor and inconsistencies came under media scan. As the home minister in the first post 1950-51 revolution cabinet headed by Mohan Shumsher Rana, Nepali Congress leader BP Koirala at times warned of not letting off newspapers that acted “irresponsibly”.

Home minister in the BP Koirala-led government, Surya Prasad Upadhyay berated newspapers “worth tupence”. Ganesh Man Singh every now and then made bitter comments on newspapers. In the early 1990s, after the reinstallation of multiparty polity, Ganesh Man Singh called journalists “prostitutes” and Interim Prime Minister Krishna Prasad Bhattarai lost his temper to an outburst: “All journalists are thieves.”

Let it be recalled, Bhattarai might have been partly affected by a long list carrying the names of journalists who received money from the state in various disguises. Shocked at seeing prominent scribes on the list, Bhattarai asked the then acting director general of Department of Information, Shailendra Raj Sharma, who had prepared the report at the premier’s directive, to drop the list without any action.

Fit to script

Not all news media are immune to unprofessionalism. Many stories are spiked if they don’t fit the “script” outlined by in-house biases and individual interests. The foreign investment story recently did not find space or airtime in quite a few big news outlets. Some dished out the names selectively shaming their own profession. Some underplayed it. Hardly did any channel bother to do follow-ups. History will be very stern on such practices.

According to a study undertaken by YouGov for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in 2018, the average level of public trust in the news in 37 countries stood stable at 44 percent. This is better than the mere 32 percent trust that the Gallup Poll found in the United States. It could be worse in Nepal where regular media criticism columns are rare, let alone timely surveys on the culture and culpability of media practices.

If bigwigs think the media are working against them, they can move the Press Council. They would have advised likewise to any who felt aggrieved by news outlets. Or is it that the government-appointed watchdog of watchdog is weak and partisan? A journalist roams crowds, events, developments, speeches and actions and potential paper trail for any piece of information with a promise of a news story. Audience trust is what airs and circulates the news media. The slightest of doubt about media professionalism erodes public credibility. When public figures indulge in media attacks, the prospects and conditions for the media grow dimmer and dangerous by the day.

You May Like This

Reimagining leadership

Right leadership ensures inclusivity in actions, inspires colleagues to think out of the box and cooperates during times of crisis Read More...

Whither Chinese consumer?

By 2020, Chinese consumers would be more relevant to the global economy than anyone except Americans ... Read More...

Fixing Afghanistan’s peace

Peace is possible in Afghanistan. But the Afghan government and the US need to be realistic about the process and... Read More...

Just In

- NRB introduces cautiously flexible measures to address ongoing slowdown in various economic sectors

- Forced Covid-19 cremations: is it too late for redemption?

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

Leave A Comment