OR

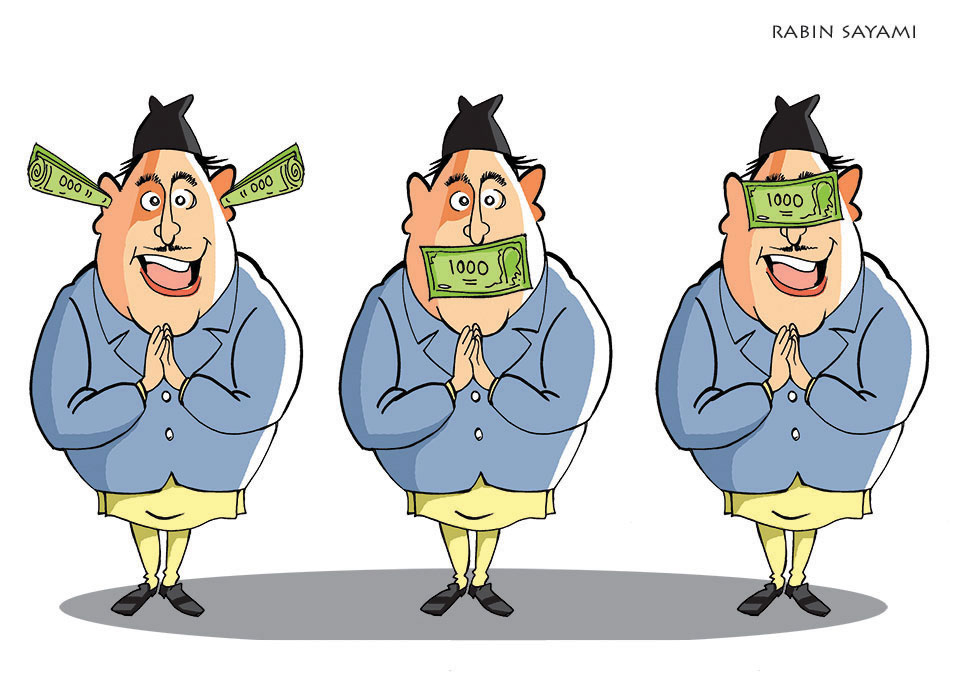

Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli has vowed to adopt policy of zero tolerance against corruption. Let’s hope he will keep the promise

Though Nepal has slightly improved in global corruption index of 2017, by jumping to 122nd spot from 131, it continues to lag behind many South Asian countries according to Transparency International Nepal’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) which generally measures extent of corruption within a country on a scale ranging from zero to 100.

Countries that score below 50 are perceived as highly corrupt and those that secure 100 are cleanest. CPI which defines corruption as “the misuse of public power for private benefit” has ranked Nepal as the third most corrupt country after Afghanistan and Bangladesh in South Asia.

Nepal’s ranking improved in 2017 because the country held local, provincial and federal elections. It is believed that elected representatives in all three levels of government will play pivotal role in eradicating widespread corruption.

Twin problems

One assessment done some years ago found that unemployment and corruption are Nepal’s twin problems which have infected political, social and economic life of Nepal. Abuse of high level power for benefits of few at the expense of many causes serious and widespread harm to individuals and society. This has happened in Nepal.

Corruption has infected every public and private institution. Few years ago, police high command was convicted of massive corruption while purchasing armored vehicles for peace force in Africa. When police who are entrusted to enforce laws to ensure transparency themselves involve in corruption we can imagine how corruption may be deeply rooted in our society.

Even non-governmental organizations who advocate for transparency are caught in massive irregularities. More than 400 humanitarian agencies contributed to post quake relief and recovery but earthquake victims are still languishing in temporary tents. This speaks volumes about their irregularities. We have 178 INGOs registered with Social Welfare Council (SWC) and 6,089 organizations affiliated with NGO Federation Nepal making Nepal the country of highest I/NGO density in South Asia. But socio-economic situations of most people remain the same. Thus we can say that corruption is exists NGOs as well.

Long term effects

Corruption is a major challenge to democracy and rule of law. If the public institutions are plagued by corruption it will erode public trust in those institutions. In long term persistent corruption will create frustration and disharmony among people compelling them to revolt against the corrupt system. Corruption also hinders social and economic progress.

Political instability is one among many causes of widespread corruption in Nepal. Prolonged transition and instability gave rise to cartels and corrupt networks. Now that we have come out this situation, we must ensure transparency and accountability in government affairs taking policy of zero tolerance against corruption.

Scores of Varieties of Democracy (VD) project suggests that political corruption is still rife in the country. Many people are elected with the campaign financed from certain interest groups. Therefore if we are serious about solving corruption problems we have to first expose the nexus between politicians and corrupt networks. Political parties should make their account transparent and submit their elections expense reports to the Election Commission.

In previous parliament some lawmakers were found involved in lawmaking process where they had a conflict of interest. While formulating Health Profession Bill (HPE) lawmakers like Rajendra Pandey and Dr. Bansidhar Mishra had registered amendments to fulfill their own interest for both of them had stakes in Manmohan Memorial Academy of Health Sciences. If this situation continues in the days to come as well corruption will flourish even more.

Corruption can be controlled if we build vibrant civil society. Citizens and activists took actions to oust corrupt people from power in countries like Guatemala, Sri Lanka and Ghana. Nepalis can make a difference if they reject corruption at all levels and demand transparency.

We need to boycott corrupt politicians, officials and business men in the society. Time has also come for reforming corruption control watchdog Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) to make it more proactive. Or we may establish Jan Lokpal (people’s ombudsmen) like in India.

Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli has vowed to adopt policy of zero tolerance against corruption. We should wait and see if he can make tangible progress in fight against corruption.

dk7030@gmail.com

You May Like This

NSU stages protest against govt's silence on co-operative fraud and Giri Bandhu cases (In Pictures)

KATHMANDU, May 15: Nepal Students’ Union (NSU) at Tri Chandra Campus staged a protest against the government's lack of interest... Read More...

Fighting hunger

Our children want to ensure that their children will live in a world where safe, healthy, nutritious food is always... Read More...

Awareness programme on 'Zero Tolerance against Corruption' held

GULARIYA, March 29: A one – day anti-corruption civilian awareness programme was held on Tuesday under the banner 'Zero Tolerance... Read More...

Just In

- Heavy rainfall likely in Bagmati and Sudurpaschim provinces

- Bangladesh protest leaders taken from hospital by police

- Challenges Confronting the New Coalition

- NRB introduces cautiously flexible measures to address ongoing slowdown in various economic sectors

- Forced Covid-19 cremations: is it too late for redemption?

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

Leave A Comment