In Nepal, Brahmin or Bahun for that matter, is an imported idea or personality. It is hard to tell who the first Brahmins were and when exactly they came to Kathmandu valley. Their emergence had begun in India as early as 2000-1500 BC along with Aryan invasion. They could have entered this land in different phases of history thereafter. But they first came to Nepal in significant numbers in the 5th century. Then they were welcomed and given privileged positions.

The Lichchhavis and the Guptas maintained them as their personal priests. This enabled them to upgrade the upper class Khas, Magars, and Newars as Chhetris, which they did by constantly demanding a high fee from them. Influx of Brahmins in Nepal began again at the end of the 12th century propelled by Muslim conquests in Northern India. As a result, many of them found refuge in the Kathmandu valley. As if to encourage them into permanent settlements here, King Jayasthiti Malla, who ruled between 1380 and 1394, introduced a definite Brahmin predominance. He formulated rules of caste system including the ones related with wearing of clothing and ornamentation which, according to the chronicles, he had accomplished under the guidance of five Indian Brahmins.

Towards the 19th century, they became instrumental in establishing the legitimacy of contemporary regimes. They could change positions and status of kings and maharajas. They changed the caste of Junga Bahadur. He was a Khas, a Kunwar but they had him, perhaps on his will and behest, adopt the title of Rana by developing a fictitious ancestry of Rajput origin from the southern plains of India. Perhaps for this favor, Jung endorsed their privilege in Muluki Ain (Legal Code) of 1854, which was strictly enforced during the Rana era and on which most of the present legal system of Nepal is based.

But there were also some prescriptions he had set for Brahmins to keep the purity of their caste. For example, the Muluki Ain decreed that any Brahmin belonging to Upadhayay class could not consume onion, garlic, mushroom, tomato, rice cooked in the kitchen defiled by birds or animals and from the hands of anyone other than Upadhaya Brahmins, among others. If a Brahmin did so, he would be deemed to have committed an impure act and would be punished. Likewise, he was strictly forbidden to indulge in sexual liaison below his caste. With ‘untouchables’, it was much more blasphemous and would entail serious punishments. These prohibitory orders, however, applied on him only if his wrongs were known.

I remember the story of Dalan, a serial that is being retelecast on Nepal Television every Thursday night at 10. I have found it to be an eye-opener to history. The story begins sometime before 1950 in a certain western district of Nepal. Anti-Rana revolution is gaining momentum in the capital and its waves are penetrating even the remote villages. Hari, a Brahmin youth, falls in love with Tulki, a Damini girl. The liaison becomes public and a local talukdar and Hari’s father send him to Benaras to avoid further scandal. But Hari, being passionately in love with her, returns. Then the pancha banishes him from the village in charge of polluting the caste. They have his head shaved on all four sides, take his janai (sacred thread) off, made to shoulder a piglet in a basket and then finally sent across the Bheri river with Tulki. From this point on, he and his descendants become Damai.

Notwithstanding this historical reality, Brahmins have served as political elites of this country. They functioned as sacred elites and also had a monopoly of the legislative and judicial functions for long. After the political changes of the 1950s, the “ever-resourceful Brahmins”, who traditionally performed the intellectual functions in the Hindu social system, lost no time in becoming the avid patrons of the secular liberal Western style educational system in Nepal. And it is a reality that this legacy has continued to this day. Even today, they enjoy liberties and privileges because of their caste. Being a Brahmin allows you to indulgences, which the caste unjustifiably justifies. He can marry a Chhetri girl or a Matwali but he will still be Bahun. In death, birth and wedding rituals, his words become law. Here I am talking about purohit bahun. He may declare the wedding over or he may call it not to have begun yet.

The people belonging to lower castes put so much of trust upon him that he can mould their innocence into anything. He is the sole authority in declaring an ominous/propitious time. In villages, a literate Brahmin, the one who can recite verses, rules over the people of other castes. They throng to his house to ask for a propitious time before they begin any work of great significance. He might, then, order his client or yajaman to perform certain rituals whose facilitator and beneficiary he will be.

But history is eternal witness. A great deal of historical, political and legal factors account for their present status. Therefore, Brahmins of today are not to blame for what they are today. Brahmins of Nepal are the result of the historical wrongs, they are products of the ruling classes’ whims and interests, they are the manifestation of privileges bestowed on them, perhaps despite their wishes, or the advantages of the kindness rendered to them for their helpless situations. They could have been anybody like Damai or Kami if their indulgences, which could have been many, with the people of lower caste were revealed to the authority. Brahmanism is not the choice of any Brahmin. I was not born a Brahmin; I knew that I was one much later.

mbpoudyal@yahoo.com

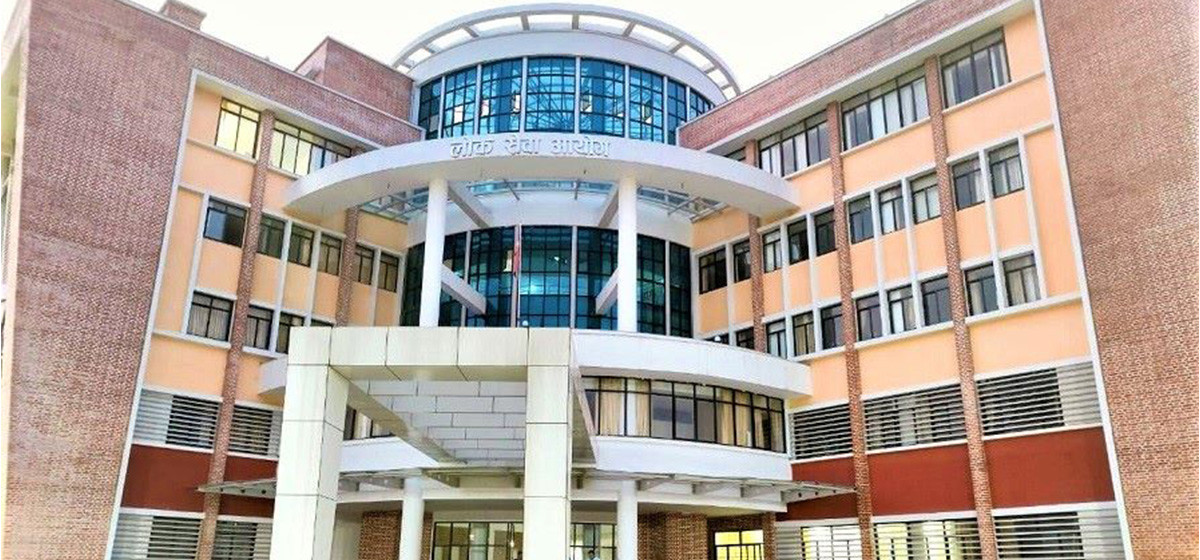

Brahmin, Chhetri applicants highest in Public Service Exams

_20220508065243.jpg)