“Plagiarism is an intellectual theft,” one of my more bookish classmates told me one day, his booming voice lending credence to the one liner. Then came the inevitable task of writing the thesis.[break]

“You just copy from an old theses lying in the Central Library and present it as your own. The job’s done,” one smart fellow suggested to me.

I was working at a weekly news magazine and I shivered at the thought of traveling all the way to TU Library in Kirtipur and rummaging through its dust-covered shelves. I was nearing thirty and VS Naipaul’s “Half a Life” seemed like a perfect choice for my thesis. I had been dazzled by his works such “The Mimic Men” that heralded post-colonialism. The more I read his novels, the more I was seduced by his evocative yet simple prose. Myself an exile trying get a toehold in Kathmandu, his notions of identity, home and half-made societies resonated with me.

But little did I know that there was a bigger Naipaul fan in my vicinity, none other than my professor.

“What do you know about Naipaul?” he thundered one fine morning, thrashing my proposal, which, to be honest, wasn’t very well-written or even argued well.

After much pondering and lingering, I decided to pursue Kate Chopin, a little known American novelist. “The Awakening,” his slim novel was excavated from its obscurity in the 1970s. Edna Pontellier, the novel’s protagonist, intrigued me. I used feminist lens to tackle the question of whether or not she awoke from the late 19th century American patriarchal society. Did her drowning at the end signal a liberation? What price did she pay for her supposed liberation? It took me six months of hard labor to satisfy my supervisors and professors that this was an original research. There were many revisions and corrections. I heaved a sigh of relief when I delivered four hard copies (I hear now they only accept CDs) at the TU Library.

Let me get over the digression and come to the point. The above anecdote illustrates that in Nepal, a student studying at government colleges, becomes familiar with the concept of plagiarism only when he or she has reached the apogee of the academic studies.

In Nepal, we’ve come to realize the magnitude of plagiarism in the academia and journalism very late. But in the West, it’s been vigourously discussed. In the newsrooms of the US, reporters are well aware of episodes of Jayson Blair, The New York Times reporter who plagiarized his way into higher echelon of America’s most respected newspaper. Recently, two episodes highlighted that even the likes of Fareed Zakaria, the Indian-origin foreign policy expert and the editor-at-large (whatever that designation might be) at TIME magazine can be caught plagiarizing a paragraph or two from another reputed magazine. For his TIME piece on gun control in America, he had lifted a paragraph from historian Jill Lepore’s article published in The New Yorker.

Another case involved Jonah Lehrer, a science writer, who had been writing for The New Yorker only for a couple of months. The author of best-selling books like “Imagine: How Creativity Works” was first caught by a Bob Dylan fan for exaggerating the legendary singer’s quotes. Later, upon investigation, it was also revealed that he had recycled his earlier blog posts for Wired magazine. Interestingly, after a week, both TIME and CNN, which had suspended Zakaria for a month, reinstated him but Lehrer was immediately dismissed from The New Yorker. As shown by the examples of Zakaria and Lehrer, writers can plagiarize with the full knowledge that it’s wrong. Usually, the excuses are lack of time and pressure to be prolific.

Closer to home, plagiarism both in academia and journalism, both in Nepali and English, is rampant. Articles have been lifted and published without citation. News get translated from English and Hindi and published in Nepali without proper attribution. Moreover, in our context, plagiarism is hardly considered a crime. Why? Because, as I outlined above, our curricula have failed to incorporate the concept of plagiarism. Therefore, the onus lies on the university teachers to create awareness about it.

It’s not that we don’t have laws governing this issue. The Copyright Act 2002 clearly says that rights to works such as paintings, essays, music, letters, reports are protected by their authors or creators. We even have Nepal Copyrights Registrar’s Office in Kathmandu where one can register a creation for its copyright and also lodge a complaint about violation of copyrights.

Indeed, writing is an arduous work. For this piece, I spent a couple of days conceptualizing it. And I spent two hours to write. So there’s no shortcut to good writing. You have to cultivate it, burn the proverbial midnight oil. The Internet, on the other hand, has made it easir to copy. But on the other hand, it’s also through Internet that the cases of plagiarism have been exposed. We writers deal with words. From the plethora of materials available on the Net, it’s tempting to copy a paragraph or sentence that perfectly fits into your writing. In the end, it’s you who decide what to do with the materials at hand.

But how to avoid plagiarism? I suggest more reading, writing, internalizing (not copying) and synthesizing.

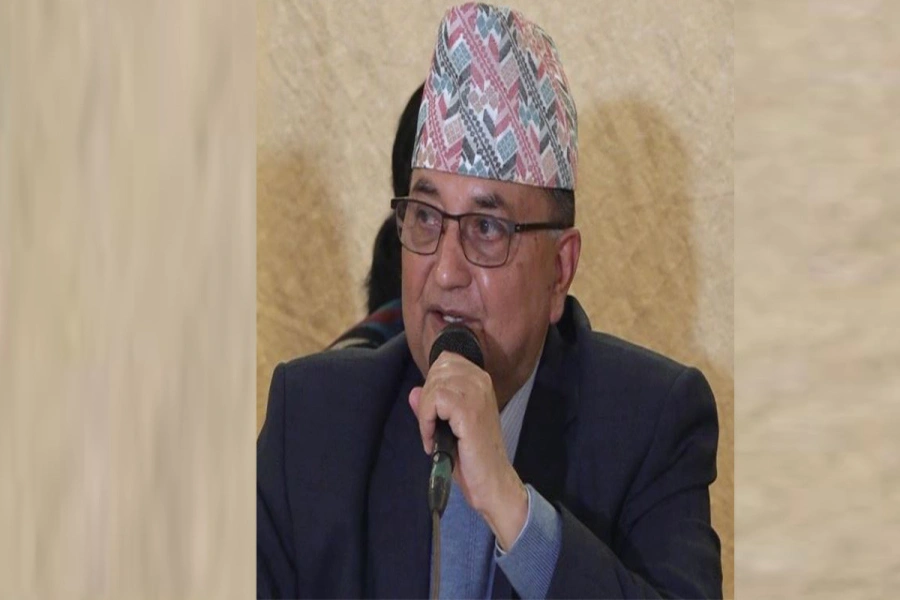

Adhikari is moderating a session titled “Plagiarism: From Academia to Journalism” at the Ncell Nepal Literature Festival on Saturday, September 22, from 12 noon to 1 pm at Nepal Academy. Panelists include Akhilesh Upadhyay, Anirudra Thapa, and Dharma Adhikari.

Shame! Shame! Shame! Shame on Nepal

_20230329122016.jpg)