Kathmandu Valley is turning into a grotesque concrete jungle with construction of more houses and buildings

The south-facing window of my house has long ceased to reveal the hills that sit on the edge of Kathmandu. When I peer out of the window, my view now consists of rectangular buildings as tall as five stories—the structures look like giant, rather geometrical monsters. New concrete replaces the old, more aesthetic houses every year as traditional neighborhoods around Patan Durbar Square, like mine, rush towards urbanization.

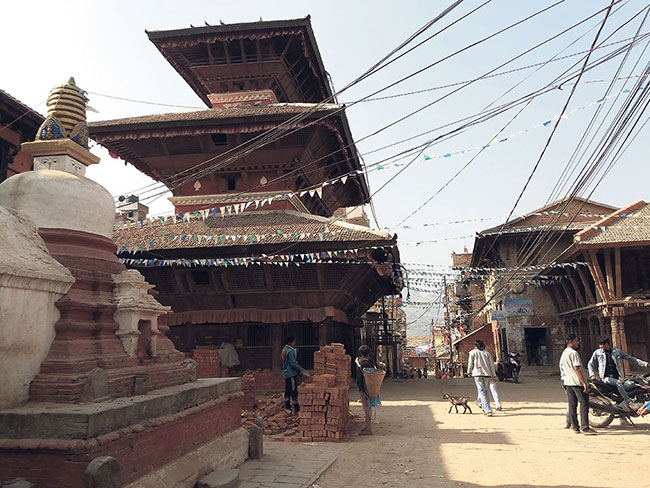

The situation is no better for Basantapur or Bhaktapur Durbar Square. With the tremendous pressure of urbanization coupled with the absence of holistic approach to heritage conservation, these historical urban centers are losing their cultural heritage. Heritage conservation is currently limited to preserving monuments and religious sites such as Durbar Squares and the plethora of temples in the city. This pays no attention to the preservation of “living heritage,” that is, traditional neighborhoods, lifestyles, and cultural practices of local communities.

Badge of honor

The integration of heritage conservation into broader urban development is urgent to preserve our cultural heritage, which includes both tangible and intangible aspects of cultural heritage.

Growing modernization has undermined the importance of traditional groups, such as guthis and bhajan khalas which give the local people their identity as an organized community. With the changes, the strengths of their culture and cultural groups have deteriorated under the pressure of modernization. The cultural groups are failing to maintain and secure cultural heritage in their neighborhood. Because of the local communities’ lack of information regarding the value of cultural heritage and importance of sensitivity towards them, many public properties such as open spaces, phalchas, traditional rest-spots, and temples in urban areas are at risk of encroachment or are in critical need of preservation.

Fragmented plots

After the earthquakes of 2015, community engagement in cultural heritage restoration is essential.

The lack of integration between urban development and cultural heritage conservation has manifested itself as developmental challenges. For example, as traditional lifestyle loses its grip on people, the fragmentation of joint families has led to division of housing plots into non-functional horizontal residential units. The urgent need to modernize the architecture coupled with failing cultural heritage has aggravated the issues of population, space, and infrastructure management. Similarly, all efforts to solve water-shortages have been focused on pipe-water supply to urban residential areas, whereas traditional water resources such as ponds, traditional water spouts, wells, and rivers have been left in utter disregard.

The swelling number of houses also suggests people seeking residence in the capital are on the rise. Nearly 1.5 million people live in the valley and it has an annual population growth rate of 6.5 percent. While an array of concrete structures have popped up around monument sites, locals need approval from their municipality and the department of archaeology for renovation and reconstruction in preserved areas. In light of that, the local population does not comply with legal provisions of conservation due to lack of incentives. In the meantime, Kathmandu Valley is turning into a grotesque concrete jungle with construction of more houses and buildings.

One popular economic activity in urban areas is to rent out rooms for residential and commercial purposes. This might improve the economic status of local communities for the short term but makes the local economy dependent on non-residents. It doesn’t offer a long-term solution to accommodate the increasing population.

Commercial pressures

On the other hand, the use of residential units for commercial purpose further displaces local communities, especially vulnerable ones. The displacement of communities can disrupt more family units, cultural customs, and practices. Such unproductive economic practice makes the local economy parasitic and destroys culture while simultaneously wasting other lucrative economic potential such as tourism.

The historical elections in June 2017 brought forward political leadership at the local level in Kathmandu Valley, and each elected official made it their priority to increase efficiency and develop cities. If they overlook cultural heritage conservation or if they separate cultural heritage from their plans of developing efficient cities, the constituencies of Kathmandu and its residents will miss incredible solutions to their problems and will lose the economic possibilities cultural heritage offers.

While development of the city is necessary and inevitable, the destruction of cultural heritage is not and should not be the part of that inevitability. Instead of allowing cultural heritage to be a victim and prey of urban development, cultural heritage conservation should be integrated into future plans for the city. This will open new avenues for exchange of knowledge between cultural heritage conservation and urban development. For instance, the layout of traditional cities is in fact more scientific with better managed open spaces, water sources, and highly connected paths. As historical urban centers, the cities of the valley can offer important insights into well thought-out urban development.