Nepal has been able to keep its sovereignty intact (to whatever extent that is), out of some tricks, some bit of wisdom and some bit of foresight displayed by our predecessors

I have been reading about Nepal’s narrow escape in its struggle for existence in various phases of history. Because Nepal is sandwiched between two giant countries that she could have been gobbled up by one of the big neighbors in the past is somehow ingrained in our national psyche. There are some who disagree with very idea of Nepal and, argue at times as if Nepal as a country should not have existed. But Nepal continues to exist (those who believe it should not have need not read further, what follows is not the story of Nepal’s annihilation).

Nepal’s story of survival invariably drags China and India into it. But the intention here is not to revive the wounds of the past and to project the countries with which Nepal struggled as “enemies.” It’s important to live with awareness of history. Unless we understand the past we cannot figure out what we need to do at the present and foresee future challenges.

Narrow escape

Imagine Nuwakot and parts of Sindhupalchok as parts of China. Hetauda of Makawanpur is our border with India. The country we know today is limited to hills and high mountains. Or imagine, we suffered the fate of Bhutan or Sikkim, that we have no control over our natural resources, cannot conduct trade with other countries the way we like and we have no army of our own. Nepal has emerged through these prospects in different phases since its unification by King Prithvi Narayan Shah.

During the first Nepal-Tibet war, Nepal had captured Kuti, Kerung and Tingri. Hostilities escalated. Negotiations were made. Tibet and Nepal signed a treaty on June 2, 1789 with Nepal promising “never to invade Tibet again.” Two years later, in 1791, Nepal broke this promise and Nepali troops plundered Tashilhumpo monastery, taking away gold, silver and jewels. It was then that Tibet appealed to China for help. Chinese-Tibetan forces had advanced up to Trishuli River and up to Nuwakot, 20 miles from Kathmandu. If Nepal had still responded with arrogance, Chinese would most likely have invaded Kathmandu.

The war ended with a treaty on September 30, 1792 to end all forms of hostilities with a provision that “China would come to Nepal’s assistance in the event of an attack by a foreign power” (this was not to happen. When Nepal appealed to China for assistance to counter British threat in 1814, China, perhaps to pay back for 1791 aggression, turned its back on Nepal).

Nepal in those days faced threats of invasion from both the south and the north. The 1792 treaty only ended one phase of threat. In around 1801, Rana Bahadur Shah (who had abdicated the throne and gone to Banaras to live as a swami, an ascetic) sought British support for his restoration. If the Company intervened on his behalf, Rana Bahadur promised to pay 37.50 percent of revenues from the hill areas and 50 percent from Tarai areas to the British India Company. And if a time should come when none of his descendents were living, he promised, “the whole of the country of Nepal shall devolve to the administration and control of the Company.” With this, the clever British must have figured out how easy it is to play inside Nepal.

Then the worst aggression followed. Many hold Bhim Sen Thapa responsible for the 1814-1816 war with British. Prominent Nepali historian Baburam Acharya, for example, solely blames Thapa for plunging the country into the war. He argues that the war was the result of inept handling of the situation by the ‘Mukhtiyar.’ “This master of conspiracy and plots lacked diplomatic acumen and failed to see through cunning policies of the British,” Acharya writes in Aba Esto Kahilai Nahos. In Acharya’s reckoning, the war and the great loss it resulted in could have been averted if the disputes in Butwal and Syuraj had been settled by conceding to the British demands.

Foreign writers do not see it that way. Perceval Landon appreciates Bhim Sen Thapa for laying the foundation upon which “both Jung Bahadur and Chandra Shamsher built up sovereignty of Nepal.” For some English historian “he was the first Nepali statesman who grasped the meaning of the system of Protectorates carried out in India. He saw one Native State after another come within the net of British subsidiary alliances and his policy was steadily directed to save Nepal from a similar fate.”

As a matter of fact, whether to go to war or to avoid it was not in Nepal’s hand. It could have been avoided only if, as Ludwig F Stiller has suggested in The Silent Cry, Nepal agreed to the British condition whereby “everything in the plains would belong to the company and everything in the hills would belong to Nepal.” The British had actually “wanted to annex all of the Tarai land up to the Churiya range of the hills.” If Nepal had accepted this proposal, Stiller writes, “It would have been more disastrous for Nepal than the actual outcome of the war has in fact proved to be.”

Nepal saved Rs 3 billion in fuel transport costs in two years o...

To yield Tarai to the Company, argues Stiller, would cause more damage to Nepal than war with all its unpleasant consequences could possibly inflict. “Continued possession of the Tarai was critical to the unity of Nepal. Without it, Nepal would once again fragment into the mini states that had been brought together with so much labor.”

Nepal stood against this proposal for as long as it could. In a communication said to have been sent by Nepal’s Chautaria Bam Shah to Major Bradshaw, Shah warns: “Never will we consent to give you the Terai, take the Terai and you leave without the means of subsistence for the hills, without it, are worth nothing. The Terai, is of no use to you because your people cannot live in it, or keep it and in wresting it from your hands, we will devastate your provinces down to the Ganges.”

The war was a tragedy foisted on the country that had little means and wherewithal to stand up to the military might of the colonial power. The disputes in Butwal and Syuraj were only an excuse. In December, 1815, when Ochterlony seized Makawanpur, the chief obstacle on the road to Kathmandu, Kathmandu had no option, but to surrender.

Phase of consolidation

After the treaty of Sugauli, Kathmandu’s focus was on regaining as much lost land as possible through all possible means. Bhim Sen Thapa played smartly under this situation. He made the British believe, mentions Leo Rose, that if they did not restore the lost lands of Tarai, China would come to Tibet. He amplified the China fear at a time when “Calcutta was deeply concerned over the presence of the Chinese in Tibet.” Gujraj Mishra and Chandra Shekhar Upadhyay were instrumental in spreading this message to British officials.

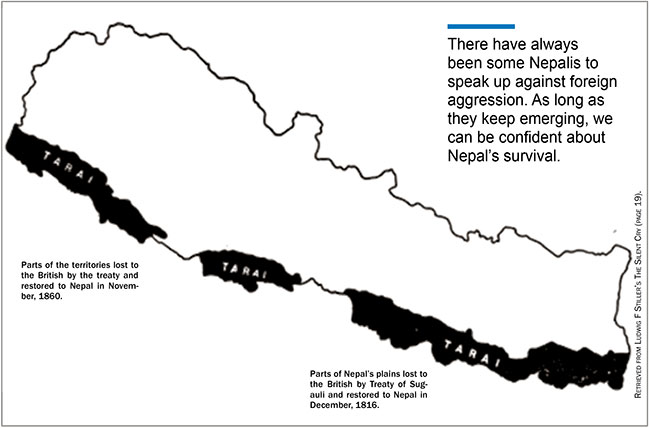

Bhim Sen Thapa with this trick could get the British restore the lost lands. In December 1816, Nepal was able to retain much of the fertile land of Tarai lost to British India (see the map below).

It is curious whether these historical memories and some foresight, or both, played out among the leaders, but on hindsight, they played extremely wisely not to once again separate the plains from the hills in province demarcation, sadly, of course, except in Province 2. One Madhes or two Madhes province model, by design or default, runs in exact parallel to lands that Nepal had restored under its sovereignty in 1816 and 1860.

The era of consolidation lasted until 1858 when Jung Bahadur brought back territories of Banke, Bardiya, Kailali and Kanchanpur, sealed Nepal’s border permanently by raising border pillars and securing the territory by setting up official boundary. Leo Rose writes that one objective of Jung was to regain all the territories lost to British India. In several council meetings held in Kathmandu, Jung had defended helping the British crush Sepoy Mutiny by forwarding the same explanation: Nepal will ask British to give back its lost land in return.

In 1919, Chandra Shamsher had asked for restoration of remaining land that had not been restored in 1858. The British in turn granted “unrestricted independence” in the treaty signed in December, 1923, laying the foundation for Nepal to conduct its foreign relation as an independent state. Leo Rose attributes survival of Nepal’s independence to Jung Bahadur and Chandra Shamsher. They “deserve recognition as two of the great heroes of Nepal,” he writes. “Whether they were acting in the interest of the nation or the Rana family—or both, as is most likely—is incidental from a broader historical perspective. They made possible the emergence of Nepal as an independent state after the demise of British Raj in India”. (To those who tell us Nepal’s national narrative was sponsored by Panchayat, Rose and Stiller were not paid agents of Panchayat).

Later rulers like Juddha and Mohan expanded Nepal’s horizon by stepping on to these foundations. Thus before India had become independent, Nepal had already made an outreach to the UK, US, France and Italy among others. By the time the Ranas left the scene, Nepal’s legation office in London (established in 1934) had been upgraded to embassy, America had recognized independence of Nepal in 1947 and Mohan Shamsher had applied for admission to the UN in February 1949.

The vulnerable 50s

The vulnerable 50s

The 50s was fraught with vulnerabilities. In lack of resources to support the new system, Nepal depended on India for revamping and modernizing civil service, bureaucracy, administration and the army.

India also assisted Nepal generously on these fronts. Matrika Prasad Koirala’s A Role in a Revolution contains exchanges of letters in which he asks his Indian counterpart Jawaharlal Nehru for every kind of assistance and Nehru promises to offer them despite limited resources in his own country. But the 50s was also the time when India was discussing whether to annex Nepal or leave as it is.

Matrika Prasad brought Indian military to Nepal and allowed Indian troops in 18 different places along the northern border. Nepal did not have its own education system and many of our fathers and grandfathers grew up learning ‘Jawaharlal Nehru is our prime minister.’ Cabinet meeting would not even start without the presence of Indian ambassador or Indian joint secretary stationed in the palace. If one of them failed to attend, the meeting would be cancelled or postponed.

This period of flux was also the period when Nepal had started to look like a semi-Indian protectorate.

Matrika Koirala realized this only when India proposed a secret treaty, called aide-memoire, which sought to completely constrain Nepal’s engagement with the outside world. The available text reads: “Nepal and India will hold special discussions on matters of foreign policy. Nepal will seek advice and opinion from India on matters of establishing relation with any foreign country, and special advice on matters of Nepal’s relationship with Tibet and China.”

There is a reason to believe such a provision could indeed have been proposed because in exchange of letters between Nehru and Koirala, Nehru at times issues veiled warning to the latter for not consulting him on issues related to foreign affairs. Ganesh Raj Sharma has written in the preface note of Koirala’s autobiography how Koirala sensed Indian intention rather too late and how his rejection of this proposal became one of the causes of his expulsion from power.

Assertiveness returns

Some of the mistakes of the 50s were corrected in the 60s. Prime Minister B P Koirala started to assert himself in matters related to China, Pakistan and Israel and other foreign affairs related issues. When Mahendra took over, he ensured the following: Nepal will have its currency of exchange, its own school curriculum and Nepal will reach out to the world independently. One of his boldest moves was removing Indian military mission and Indian check posts from northern border points.

It is hard to say why King Birendra had to import arms from China (Nepal was not fighting any war) at the cost of causing great annoyance to India. But India responded with disproportionate aggression. It first imposed crippling 18 months blockade, in support of, as it claimed, the anti-Panchayat agitation of 1989. And then it proposed another secret treaty (said to be brought to the king by then Indian foreign secretary S K Singh), as a condition for India lifting the blockade and safeguarding the future of monarchy.

This secret proposal included provisions even more harmful to Nepal than that of aide-memoire of the 1950s. India sought not only to conduct Nepal’s defense and foreign relations but also priority rights and control over matters related to our industry, commerce and water resources. Those working inside the palace in those days say King Birendra then chose to compromise with Ganesh Man Singh, “the son of Nepal,” rather than capitulating to foreigners. When Krishna Prasad Bhattarai went to India for a visit in 1991, he defended arms purchase dismissing the Indian concern by saying “Nepal brought arms from China only because they were five times cheaper than those that could be supplied by India.” In 1994, Bhattarai spoke of this secret treaty and mentioned that if those terms had been accepted, Nepal would have ended becoming “another Bhutan.” Year 2015 is fresh in our memories.

Secret of survival

Nepal has been able to survive and keep its sovereignty intact (to whatever extent that is), out of some tricks, some bit of wisdom and some bit of foresight displayed by our predecessors. Irony of history is you have to rely on whatever facts, laden with fiction as well, are handed to you or whatever facts you can grasp. Another irony of historical facts is they are true only as long as alternative truths and facts challenge them.

Based on available materials (or the ones I could cover for this article), we can say that some of our rulers, even those who at one time literally submitted to foreign powers, have strongly stood in favor of the country during the most difficult times. Yes they used guiles, even evoked jingoism, but the end result has been continued survival of the country.

In 1816 it was Bhimsen Thapa, in 1858 it was Jung Bahadur, Chandra Shamsher in 1923, BP and Mahendra in the 1960s, Birendra in 1990.And in 2015, like or not, it was KP Oli.

What often get lost in narrative of survival are characters who support their rulers to take the best decisions. Who may have advised Nepal Durbar in 1792 to make amends with China? Who were behind the decisions taken by Bhimsen Thapa? Was the decision of removing military posts only that of King Mahendra and Kirti Nidhi Bista? Who may have advised Jung to secure Nepal’s border with Junge Pillar? And how do people, and what cost, contribute to country’s survival? (Hopefully some historians will explore this side of the story sometimes in the future.)

Leo Rose argues that one secret of Nepal’s survival is its location between China and India. For me, it is more than that. This country has survived because our rulers have taken some of the best decisions during some of the worst times.

Historically, there has never been a consensus in Nepal regarding how to deal with foreign intervention. A group of people including the intelligentsia, from the days of Bhim Sen Thapa to this day, have always advocated submission. But then another group arises and speaks up. It’s no wonder that the party that once did not call blockade by its name is today the biggest critic of the blockade. And those who derided Oli for being a nationalist are today deriding him for not being nationalist enough. There have always been some Nepalis to speak up against foreign aggression, even by risking their lives and careers. As long as such people keep emerging, we can be confident about Nepal’s continued survival.

Yes, almost every country is fraught with its own problems. This quote attributed to American statesman Carl Schurz could be a good guide: “My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right.”

(References apart from the ones mentioned: Perceval Landon’s Nepal, Saradar Bhim

Bahadur Pandey’s Test Bakhatko Nepal,

Rishikesh Shah’s Modern Nepal, Leo E Rose’s Nepal: Strategy for Survival and Sanjay Upadhyay’s Nepal and the Geo-Strategic Rivalry Between China and India)

mahabirpaudyal@gmail.com