OR

Opinion

These last few weeks, I had opportunities to interact with a variety of entrepreneurs—taxi drivers, pharmacists, retail store owners, streetside vegetable vendors, automobile mechanics, non-profit organization directors, and for-profit organization directors. One consistent theme that emerged out of these interactions was that Nepal does not have a supportive climate to be an entrepreneur.

Through these interactions, it became clear to me that there are hurdles too high for an aspiring entrepreneur to clear through to succeed. While there are many challenges, I wish to highlight four crucial ones.

Challenge to build human capital

There is a catch-22 situation happening here in Nepal: we cannot have good economic growth without good quality human capital, and good quality human capital usually develops in a fast-growing economy because the fast-growing economy provides ample opportunities for the human capital to improve its quality.

In Nepal’s case, the situation looks especially dire because whatever quality human capital we have is in a hurry to leave the country. There are push and pull factors for this phenomenon. Push factors include poor business and employment climate here at home. Pull factors include higher pay and better standard of living overseas. Whatever the reasons may be, any quality human capital we have is in a rush to leave. The masses of Nepalis migrating overseas for work every single day through Tribhuvan International Airport is sufficient proof of this.

What does this out-migration do?

I used to travel to remote villages of Nepal and find village after village in the mid-west and far-west losing their prime working age population to other countries. That was 10 years ago. I cannot imagine what those villages look like today. Going by the news reports, I believe the situation has worsened.

What is the government doing to alleviate this situation?

I pored over the recent national budget. I found that while the budget supports several institutional capacity building endeavors, it mentions two capacity-building supports to individuals: capacity of the youth will be developed and made employable, and capacity building programs for fiscal management will be carried out at the provincial and local levels. There is also the NPR 470 million budget for using agriculture and livestock graduates as technical assistance to farmers.

Those three initiatives for individuals could be considered human capacity development supports in the current budget. While the economic impact of institutional capacity building cannot be understated, one cannot expect the country will translate its human capital into economic growth with three capacity building programs alone. More needs to be done.

A country needs strong human capital to create more entrepreneurs.

Weak national initiatives to support entrepreneurs

There are national level initiatives like Make in Nepal and Made in Nepal campaigns to highlight, promote, and develop local products and support an entrepreneurship culture. Those initiatives have lofty goals, which can only be fulfilled with more individual-level capacity building training and courses, critically at the provincial and local levels which is where entrepreneurship is more likely to develop and grow. This will require substantial local, provincial, and federal support.

The recent budget had several provisions to support Make in Nepal and Made in Nepal initiatives: NPR 950 million grant scheme for grain and livestock insurance; NPR 2.15 billion to connect centers of local governments by road to the provincial capitals or the nearest national highway; NPR 330 million for management and upgrade of industrial corridors; NPR 540 million to build Special Economic Zone infrastructure; NPR 410 million to build industrial villages. Such provisions may work together to bring the large-scale visions of Make in Nepal and Made in Nepal to fruition.

However, those initiatives do not support an entrepreneurship climate. I found one direct and one indirect mention in the budget to support individual entrepreneurs: NPR 1.2 billion scheme to attract young manpower to agriculture and livestock business and entrepreneurship; and concessional loans to sportspersons through the Youth Self-employment Fund. Although the budget also states returning migrant workers will be encouraged to become entrepreneurs, details are lacking on how this will be accomplished.

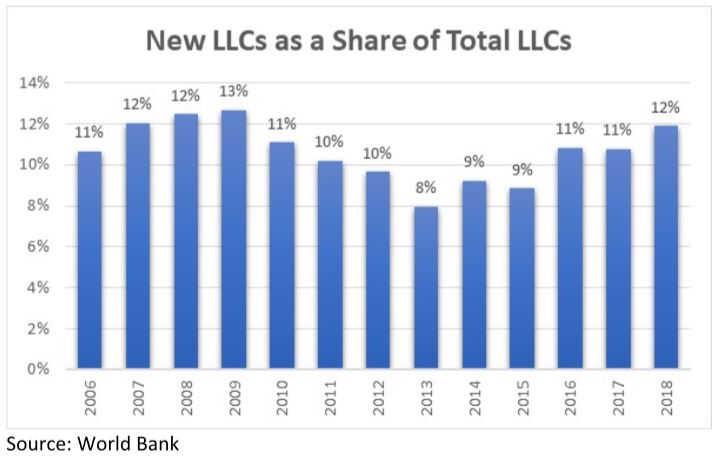

The lack of government support shows up in the data. Registration of new Nepali businesses peaked in 2009 (13% of total registered businesses that year were new businesses), after which the ratio declined to 8% in 2013. There has been a gradual progress since then, but we have miles to go.

What kind of support is needed to foster and develop more entrepreneurship? A few solutions come to mind: removing or easing regulatory burdens on new business registrations; providing or easing the access to capital for start-ups; and setting up government programs to support entrepreneurs.

Considering the hassles that the Nepal government engaged in with ride sharing apps and the unfavorable climate faced by Yatri motorcycle company due to regulatory constraints are examples showcasing the ineptness at the federal level to recognize entrepreneurship and facilitate it. Unless that changes, entrepreneurs will continue to face uphill battles.

Given the scant support to entrepreneurship in the federal budget, it will also be interesting to see if provincial budgets will take up the baton to help entrepreneurs.

Challenge to turn returnee migrant workers into entrepreneurs

Past studies in Africa and China have shown that many migrant workers acquire significant skills and accumulate enough capital to become entrepreneurs upon returning back home. If out-migration for work leads to significant skills and capital accumulation leading to entrepreneurship, this can be a powerful poverty alleviation strategy for countries to pursue.

Does this happen in Nepal?

A study by the International Labor Organization found that the answer is ‘maybe not’. Returnee Nepali migrant workers do not save enough to start a business, and if they do start a business, it is out of necessity. This is especially true for returnees from India and Saudi Arabia. In addition, the study found that Nepali migrant workers who actually manage to save some of their income prefer to purchase real estate assets over becoming an entrepreneur and starting a business.

Those who do become entrepreneurs and start businesses report facing difficulties: not knowing legal requirements of starting a business and not knowing where to go to access financing. There are a few government programs, like the Youth and Small Enterprise Self-employment Fund (YSESF), that provide some support but returnees are unaware and the programs themselves are insufficient. For example, the YSESF provides low-interest loans to banking, finance, and cooperative endeavors. Those are not “youth and small enterprise” opportunities.

What the YSESF supports are maybe not the kind of entrepreneurship ventures a returnee migrant worker is hoping to start or can afford to.

There is a mismatch even in the nomenclature of government programs purporting to support individual entrepreneurs.

Endangered gendered entrepreneurship

Finally, there is a gender dimension to entrepreneurship in Nepal, in that we have failed to turn our mothers and sisters into entrepreneurs.

In 2020, just over 10% of business owners and business directors in Nepal were women. In 2020, just over 52% of the Nepali population was female. In the last decade, the share of female business directors and business owners have declined while the share of sole proprietors has increased.

The rise in sole proprietorship is probably the result of what the ILO study earlier found: insufficient skills and capital lead to returnee migrants becoming sole proprietors, not out of volition but out of necessity to provide for one’s family.

There is a clear mismatch in Nepal between potential and fulfillment when it comes to female entrepreneurship. Half of the country’s population is not only unable to improve its entrepreneurship ambitions, but the last decade has actually seen this ambition dwindle.

This failure to create more women entrepreneurs must be addressed through government policy. However, the recent budget gives no indication of this support.

You May Like This

Tourist arrivals up 18% in first seven months, entrepreneurs unimpressed

KATHMANDU, Aug 18: Tourist arrivals in 2018 has continued to break the old records of the country. Recording a remarkable... Read More...

Party's name will be Nepal Communist Party after merger: Leader Nepal

KAILALI, Feb 9: CPN-UML leader Madhav Kumar Nepal said that the name of the new party after merger between CPN-UMLand... Read More...

Nepal vs Kenya: Five crucial things Nepal looks for second match

KATHMANDU, March 12: Nepal is taking on Kenya on Monday in the second match of the ICC World Cricket League... Read More...

Just In

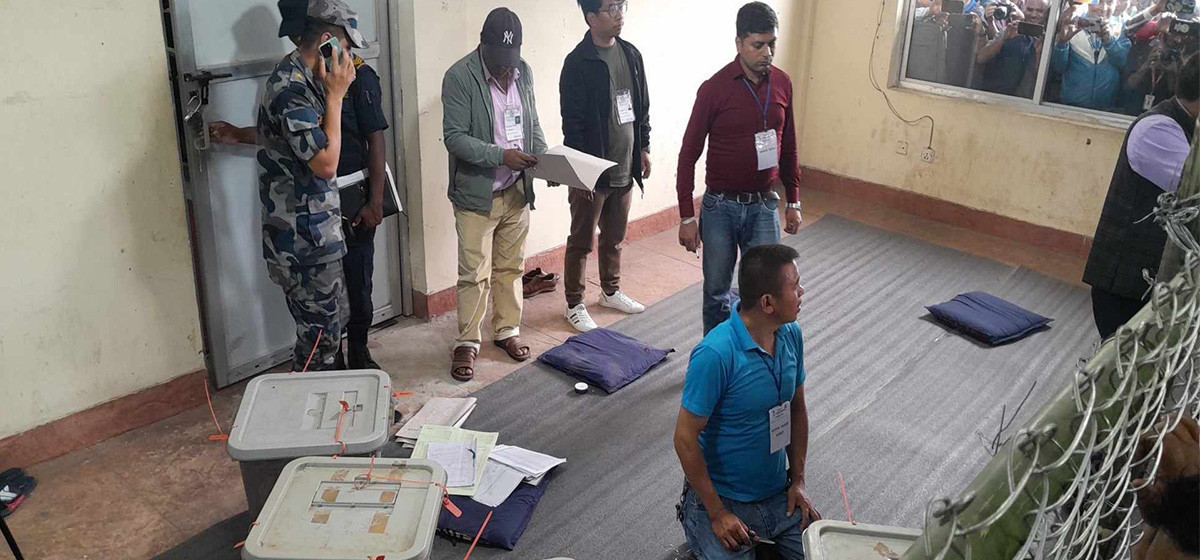

- Vote count update: UML candidate continues to maintain lead in Bajhang

- Govt to provide up to Rs 500,000 for building houses affected by natural calamities

- China announces implementation of free visa for Nepali citizens

- NEPSE gains 14.33 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.68 billion

- Tourists suffer after flight disruption due to adverse weather in Solukhumbu district

- Vote count update: NC maintains lead in Ilam-2

- NAC's plane lands at TIA after its maintenance in Israel

- Indian Ambassador assures of promoting India's investment in Nepal

Leave A Comment