OR

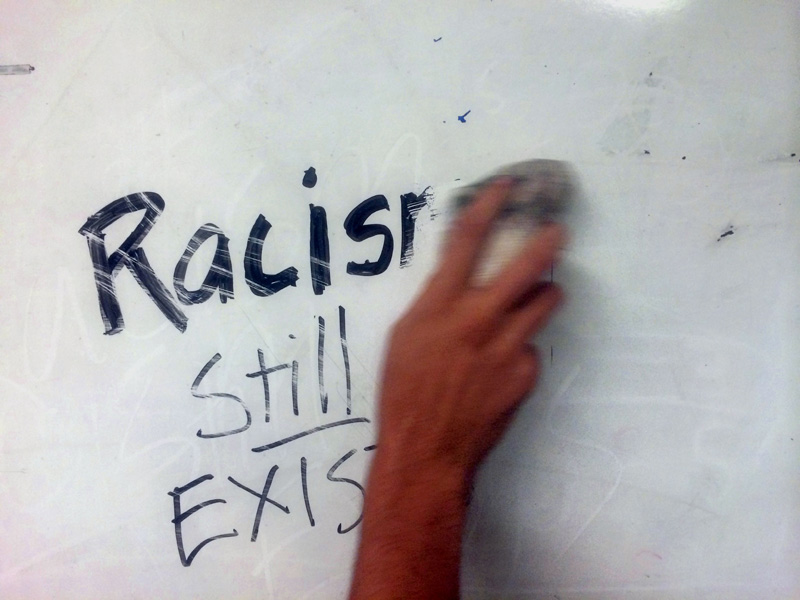

The thought seems to be that if difference is unaddressed, it will cease to exist and to shape people’s experiences. That is not so

I have a distinct memory of sitting on the swings in my school playground with one of my closest friends in sixth grade. We were both in afternoon stupor after lunch, when she pointed her finger towards a younger student walking past us—dark-skinned, oiled slicked-back hair—and said to me: “Chi chi Abha, look at that, this school is being taken over by Mades and Madises, what a shame, is nothing just ours anymore?”

I was old enough to know that I was a ‘Madise’; my friend had no idea; and I felt a vague twinge of wanting to defend myself and the little girl being scrutinized. But in what I now remember as a remarkable act of cowardice, I nodded sheepishly at her, not saying anything, and shifted the conversation uneasily back to moaning about maths homework.

The word ‘Madise’ conveyed many things in my school career—dirtiness, poverty, stupidity, invader status, general worthlessness, and my response to the constant barrage of depreciation and belittling comments was not to try to engage my Pahadi-Bahun and Chettri friends in conversation or to challenge them, but to distance myself from ‘Madise-ness’ that I knew was mine but had internalized as negative in every way.

My family left Kathmandu to go to Tarai every year for Chhath, a festival that is a distinctly Madhesi one, and through second to eighth grade, I remember making up elaborate lies about why I was missing school for a couple of days so that my classmates wouldn’t figure out that I was celebrating a Madhesi holiday and conclude that I was a Madhesi. Some years it would be a case of viral fever, other times a distant cousin’s wedding, and one year, pressed to come up with an original lie, I told my peers that my grandmother had died.

Although I am now deeply ashamed of the web of deceit I felt that I had to construct in order to hide the fact that I was Madhesi, I recognize that it was as much a tactic of self-defense as anything else.

Owning Madhesi-ness would mean being teased (bullied) as dhoti, being mocked as an ‘Indian interloper’, and the greatest of horrors for a shy middle-schooler, being seen as different and therefore constantly conspicuous.

I used my phenotypically Pahadi-passing features to my advantage and laughed at racist jokes about paan-chewing Madise tarkari-sellers, despite the unease I felt in the pit of my stomach. I pretended I was one of them to partially escape the indignity that comes with being Madhesi in this country.

I don’t blame my peers for their casual (if deeply hurtful) racism towards Madhesis, Madwadis, and anyone who might look like they might be from south of Hetauda. Just as I was lying to blend in, as kids do, they were regurgitating comments that their parents and other adults in their lives made, as kids do. Addressing the racism that seems to flow through the veins of many adults in Pahadi communities is a whole beast to tackle in itself, but what I am deeply disappointed at, looking back, is the complacency of teachers in never challenging the racism that was becoming reified as parts of their students’ personalities as years went by.

Many of my teachers in school were wonderful educators, and cared deeply about their students’ well-being in every way, which is why the complete silence surrounding matters of race, ethnicity, and belonging, matters that directly affected their most vulnerable students on an everyday basis is so baffling.

I can appreciate the fact talking about racism in a school setting is uncomfortable, challenging, work, and many teachers, however well-intentioned they might be, grow up with the very stereotypes about marginalized Nepali identities that need to be confronted in an educational environment. However, never talking about power and inequality is definitely not the answer—and harms students in profound, lasting ways.

Long after the fall of Panchayat and the supposed introduction of inclusive parliamentary democracy, the discussion of identity in most Kathmandu schools still falls within the paradigm of Euta raja, euta desh, eutai bhasa, eutai bhesh (‘One king, one country, one language, one appearance’).

Challenging hegemonic Pahadi upper caste-ness is still sacrilege, and it appears as though the thought is that if difference is unaddressed, it will cease to exist and to shape people’s experiences.

I feel like I can say without an iota of doubt that for students who are Dalit, Janjati, Muslim, Madhesi or Madwadi, this is not true.

I was lucky enough to have grown up in a family that talked about Pahadi hegemony and the need to resist misrepresentations of Madhesi-ness regularly (arguably even excessively), and sometime during my teenage years, evasion of the fact that I was Madhesi became unthinkable to the point where I would interject with “Just so you know, I’m Madhesi!” at completely random points in conversation so I wouldn’t have to break into a long tirade about why casual racism was so damaging when something racist inevitably came up.

Many children coming from the same kind of educational background that I did do not accept their Madhesi-ness with age and maturity—in fact, the need to pass off as Pahadi begins to feel more and more necessary as negative repercussions of Madhesi identity—discrimination in admission to colleges, in access to the job market, and in political careers, among any number of things—becomes more and more salient.

While I don’t think schools are single-handedly responsible for the self-loathing that comes to characterize how many Madhesis understand themselves, I think the power of schooling in undoing some of the damage that decades of discrimination has done and affirming identities that are constantly degraded cannot be underestimated. For starters, I think teachers can choose to tell their students that no, not all Madhesis are either vegetable-sellers or Indian immigrants, no, there is nothing wrong with being either a vegetable-seller or an Indian immigrant, and yes, Madhes and ‘Madhises’ belong in spaces in Kathmandu as much as anybody else does.

The author is pursuing a degree in anthropology and religion at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania

You May Like This

More students switching to community schools from private schools

SURKHET, April 19: Bandana Khadka of Birendranagar-3 recently admitted her two sons to one of the oldest community schools of the... Read More...

In lack of good schools in Siraha, children go to Indian schools

SIRAHA, Dec 11: There are ample of private and community schools in the district. However, many Nepali children go to Indian... Read More...

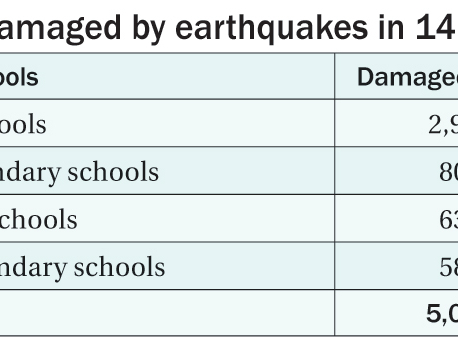

Quake-hit schools in 31 districts to be rebuilt within 3 years

KATHMANDU, Aug 10: Hundreds of students in earthquake-hit districts will have to study under tents and inside cracked buildings risking... Read More...

Just In

- Nepal at high risk of Chandipura virus

- Japanese envoy calls on Minister Bhattarai, discusses further enhancing exchange through education between Japan and Nepal

- Heavy rainfall likely in Bagmati and Sudurpaschim provinces

- Bangladesh protest leaders taken from hospital by police

- Challenges Confronting the New Coalition

- NRB introduces cautiously flexible measures to address ongoing slowdown in various economic sectors

- Forced Covid-19 cremations: is it too late for redemption?

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

Leave A Comment