The anti-reservation movement spearheaded by students in neighboring Bangladesh has taken a new turn. When the anti-reservation movement shifted to an anti-government movement and former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina failed to address the protestors' demands before it was too late, she was not only deposed but also forced to flee the country. Against this backdrop, Republica sat with former Chairman of National Inclusion Commission Dr Ram Krishna Timilsina to learn about various aspects of the reservation system that Nepal has embraced following the success of democratic uprising in 2006. Excerpts:

Republica: The movement in Bangladesh over the issue of reservation brought political upheaval, and PM Sheikh Hasina had to flee from the country. What message does that movement give to Nepal?

Dr Timalsina: The issue of reservation has become a significant topic of discussion, especially in South Asia. It encompasses historical, social, constitutional, and legal perspectives. The recent political turmoil in Bangladesh and the historic judgment of the Supreme Court of India highlight the need to review the reservation system in South Asia.

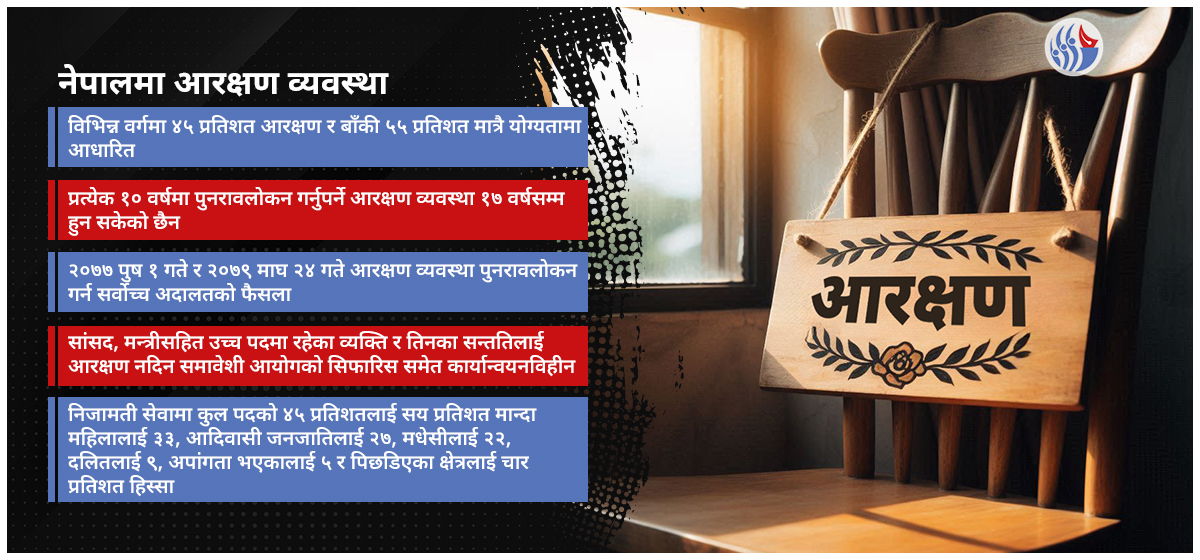

The original objective of the reservation system seems to have been partially fulfilled, but there have been distortions within its implementation. In Nepal, the reservation system was introduced in the civil administration in 2007, with a provision to review it every ten years. However, it has been 17 years now, and there has not been a comprehensive review.

Last year, the National Inclusion Commission conducted a study on the status of inclusion in civil service. The study indicated that Nepal's reservation system needs some review to make the presence of reserved groups more scientific. Following an order from the Supreme Court, the commission also studied a case filed by Binay Panjiar.

The study revealed that, in South Asia, the ‘upper class’ within the reserved groups benefited more than others. The reservation system did not reach the voiceless individuals it was intended to help. It seems necessary to reconsider the reservation system from legal, constitutional, and social perspectives.

The class outside the reservation in Bangladesh showed dissatisfaction. Is a similar dissatisfaction seen in Nepal?

The class outside the reservation in Bangladesh showed dissatisfaction. Is a similar dissatisfaction seen in Nepal?

RSP Chair Lamichhane’s campaign event barred in Nawalparasi Wes...

Yes, there appears to be significant dissatisfaction in Nepal as well. There are strong voices both supporting and opposing the reservation system. While serving on the National Inclusion Commission, I observed that within the Dalit community, not everyone benefited equally from reservation facilities. Often, a single family, individual, or caste within the Dalits received more benefits. This indicates a need for a comprehensive approach to reservation. Inclusion is more than just reservation; it's a broader system.

For example, in 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the quota system unconstitutional. Similarly, the Supreme Court of India suggested removing the 'upper class (Tarmara Barga)' from the reservation or 'reclustering' the reservation system. Both Nepal's Constitutional Commission and the National Inclusion Commission have recommended that the reservation system should not continue in its current form. Last year, the National Inclusion Commission recommended creating a 'benchmark' within the reservation system based on property, position, and access. The Supreme Court of India has echoed similar sentiments. It seems that India has also learned from Nepal in this regard.

Can you share with us the key recommendations you have made in the report?

Our recommendations focused on ensuring fairness in the reservation system. Specifically, we suggested that individuals in the Kathmandu Valley with assets of over Rs 50 million, real estate, ministerial positions, political appointments above an honorable position, post in government service above joint secretary, or those who have studied at internationally-renowned universities on self-finance should not be eligible for reservation for their children’s education.

Our study found that individuals who have benefited from reservation once should not receive it again. Additionally, there are 74 castes in Nepal with no presence in the state system, and their population is more than 10 percent. We recommended creating a cluster to address these underrepresented classes. Removing the upper class currently benefiting from reservations would make the system more just.

For example, among tribal groups, Newars or Thakalis often have a higher economic status, whereas the poor Khas Aryas or Musahars living in the Terai are much less privileged. This disparity highlights the need to view reservation as a category, not as a caste. One key conclusion of our study is that the reservation system should not be solely based on caste.

The Government of Nepal had requested the National Inclusion Commission to review the reservation system following the Supreme Court's order. The commission's report on this study is currently being prepared. The Medical Education Commission has also conducted a study on this matter. All these studies indicate the necessity to review Nepal's reservation system.

It is essential to address current inconsistencies through legal and practical amendments, considering inclusion from a broader perspective. The present understanding of inclusion is very narrow. I believe it is necessary to develop a separate educational strategy for the economically and socially backward Dalit community. A quota for other categories is not reasonable.

For the 74 low castes, we recommend providing opportunities in political, public service, and private sector jobs by creating a separate cluster and enhancing their capacity. Advancing solely on numbers without increasing capacity may negatively impact our democratic and merit-based systems.

Is there requisite political will for these overall reforms in Nepal?

When it comes to political parties, the issue often revolves around vote banks. This creates an environment where progress is hindered because both national and international players use political or diplomatic methods excessively. However, if the leadership genuinely wants to reform the system, it can be made more scientific by reviewing and rethinking it. This can be achieved by focusing on accountability to the people, promoting good governance based on merit, and balancing social justice.

The current government has almost a two-thirds majority. Can we expect anything from it?

If the government considers the current approach in India, the wave seen in Bangladesh, and the questions raised earlier in Nepal from various angles, then political parties can address these issues in Nepal. Our reservation system is based on caste, but it needs to be based on class. For example, within the Dalit community, a separate cluster is needed. Madhes is a geographic region, yet there's no clear definition of Madhesi. Reservations given to Muslims based on religion or to women based solely on gender do not seem just.

For instance, why do upper-class women need reservations? If a woman is self-sufficient, internationally educated, and capable, she does not need to benefit from a reservation just because she is a woman. Similarly, those who have achieved excellence in intellectual, business, or other fields and have a high quality of life do not need to take advantage of reservation.

The sustainable development goals state that ‘no one should be left behind.’ This means the state should have detailed statistics on individuals and provide reservations based on individual needs. When placed in groups, the benefits often go to the upper class of that group. For example, a judgment by a Dalit judge in the Supreme Court of India, which other judges agreed with, highlighted that higher-ranking individuals within a reserved class who already benefit from reservations tend to maintain control, preventing others from accessing these opportunities.

It appears that those who have already benefited from reservations and have the potential to continue benefiting often wish to keep control, thus preventing others in the same class from advancing.

Do you think it is time for Nepal to review and revise the reservation system?

Yes, it has become necessary. It is crucial to ensure that the benefits reach those classes or individuals who have not yet benefited. Our conclusion is that those who have already benefited once in the name of the group should not receive benefits again.

-1200x560-1772467693.webp)