Hydropower projects must factor in the environmental costs too

While Wayanad in Kerala limps back to normal life after the devastating landslide last month, a landslide on Tuesday (August 20, 2024) in Sikkim caused damage to six houses and a building of the National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) at its Teesta-5 hydropower station in Gangtok. There is no comparison of the impact of the event in both places, as there was no loss of lives or injuries reported in Sikkim. However, the cause for concern is that this is the second natural-disaster-led assault on a hydropower project along the Teesta.

How sustainable is hydropower development in Nepal?

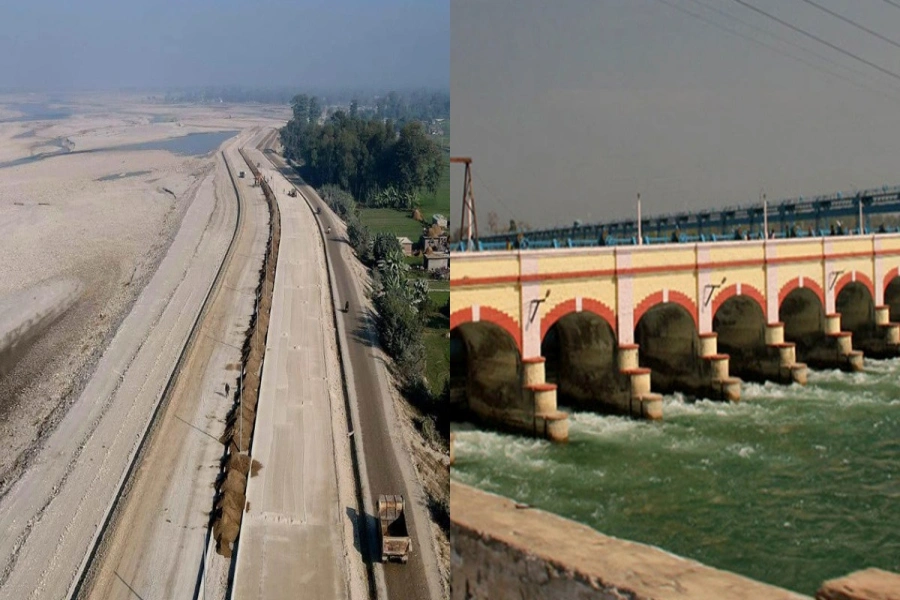

A deluge from the South Lhonak glacier in North Sikkim last October washed away the Chungthang dam that was critical to the Teesta-3 power station (which is not operated by the NHPC). The Teesta-3 (1,200 MW) power project was the largest hydroelectric power project in the State until it was effectively grounded after the outburst. Only a tenth of the power originally being supplied by the project is now available. The Teesta-5 project, at 510 MW, has also been made non-functional since the glacial lake outburst.

The disaster shines a new light on an old, but never quiescent, conundrum posed by hydropower projects. From initial proposals nearly three decades ago to have 47 power projects along the run of the Teesta in Sikkim and West Bengal, only five projects exist and about 16 are in various stages of consideration. A tributary of the Brahmaputra, the Teesta river originates from the Tso Lhamo Lake at an elevation of about 5,280 metres in north Sikkim.

The river travels for about 150 km in Sikkim and 123 km in West Bengal, before entering Bangladesh from Mekhligunj in Cooch Behar district; it flows another 140 km in Bangladesh and joins the Bay of Bengal. In theory, the river’s course through undulating terrain is what tempts governments to extract as much benefit as possible for power projects. Through the decades, several companies have bid for projects auctioned out by State governments but the process has rarely been without complications.

It has been a complicated exercise in balancing the environmental risks, costs of properly insuring for those risks, public perception and aiming for profit. In the case of the Teesta-3 project, reports have emerged that the developers, in order to save on costs, built a concrete-faced rock fill dam as opposed to a concrete gravity dam — one reason why it was completely washed away. Environmental impact assessments of hydropower projects in the region must give a clear estimate of the actual costs involved. This will not only bolster public faith in these projects but also be environmentally sustainable.

Source: The Hindu (India)