A new form of corruption is being institutionalized in Nepal. It is very similar to the problem of match-fixing in sports but goes by the name of electoral alliance! It is a pre-fixed or advance agreement between political parties, to form alliances whereby the members share electoral constituencies, deciding which party candidate to field where and whom to support, before going to the polls. It is a strategic move to defeat political opponents and gain electoral victory. In sports, match-fixing is a corrupt activity and is hence punishable. But political match-fixing is yet to be introduced to the lexicon of Nepali corruption. Unlike in sports, there may not be a direct under-the-table cash transfer in political match-fixing but it is definitely having far-reaching intended as well as unintended political consequences.

Electoral alliances

Electoral alliances were first observed in the local and federal and provincial elections in 2017 when the CPN-UML and CPN (Maoist Centre) allied to contest the elections. During the local elections, the Nepali Congress allied with the CPN (Maoist Centre). However, compared to the electoral alliances in 2022, the alliances in 2017 were ‘mild’.

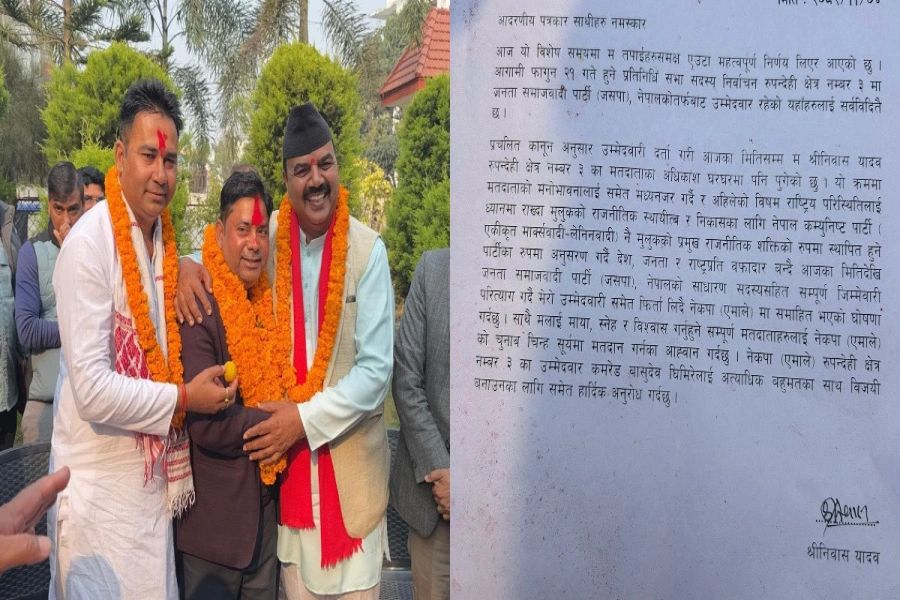

In 20222, broadly, there were two electoral alliances. The first one was the five-party ruling alliance headed by the Nepali Congress, comprising the CPN (Maoist Centre), CPN (US), RJM and LSP as members. The second one was the opposition alliance, led by the CPN-UML and supported by smaller parties like the RPP, RPP-Nepal, JSP and others. The severity of an electoral competition reflects the intensity of an electoral alliance – each accusing others of being a thug-bandhan, that is, the deformation of guthbandhan or alliance in Nepali.

The genesis

Political class is dishonest in Nepal: Political analysts (with...

In the past, we experienced the formation of several coalition governments. But these exercises were, basically, a result of a hung parliament situation brought about by post-election outcomes. Given the country’s demographic situation with one-third of the population being bahun-chhetri, one-third janajati and the other one-third terai-madhes population and mixed election system with 60 per cent MPs to be elected through the First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) or direct elections system and the remaining 40% through the Proportional Representation (PR) system, it is near impossible for any single party to secure simple majority in parliament. The political parties, now, reason that due to the high cost of elections, they are forced to go for electoral alliances.

The formation of electoral alliances is also rooted into our consensus culture that got implanted during more than the decade-long transition period (2006-2017). The culture of consensus was defined as a participatory, inclusive and consensual decision-making process but, in practice, it turned out to be bhaagbanda (sharing of spoils), on a turn by turn rotational or aalo-paalo basis. Remember, how the All-Party Mechanism (APM) had to be quashed by the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) for breeding a culture of corruption in the country?

The formation of electoral alliances and its consequence in the making and breaking of coalition governments, party splits, defections, horse-trading and buying and selling of MPs will continue to feature in Nepali politics. This implies political instability and turbulence to be the core feature of Nepali politics.

Dysfunctions of ex-ante electoral alliances

As compared to ex-post electoral alliances, there are several dysfunctions with ex-ante electoral alliances.

The first and foremost is the squeezing of political space. A voter is forced to vote for a candidate or even a political party regardless of his or her preferences. In the end, political match-fixing makes a mockery of democracy. It robs the people of competitive elections and prevents them from electing a capable and a qualified candidate. Basically, the people are turned into sheeples. Probably, in response to political match-fixing, voters have started to speak out loud for the “right to reject” and “right to recall” electoral system. “No, Not Again” (NNA) became a catchphrase during the election campaign and the Supreme Court had to interfere to stop banning the NNA campaign.

Second, it has produced absurd voting outcomes. For example, the Madhav Kumar Nepal-led CPN (US) which bagged 10 seats under direct elections was hardly able to secure 300,000 PR votes, a threshold required to qualify for a national-level party. Compared to this, the RSP which bagged just 7 FPTP seats was able to secure more than 1.1 million PR votes and put it on a par with the Maoist Party. A similar comparison can be made between the two big parties like the Nepali Congress and the CPN-UML. The Nepali Congress secured 55 FPTP seats with 2.7 million PR votes while the UML secured 44 FPTP seats with 2.8 million PR votes. Similarly, the Maoist Party which secured 17 FPTP seats was able to secure only 1.2 million PR votes. Much of this discrepancy between the FPTP wins and PR votes can be ascribed to electoral alliances. Contesting elections in a large number of constituencies is like casting a large net to catch fish (votes). The RSP contested in 131 constituencies and was able to collect a swath of PR votes.

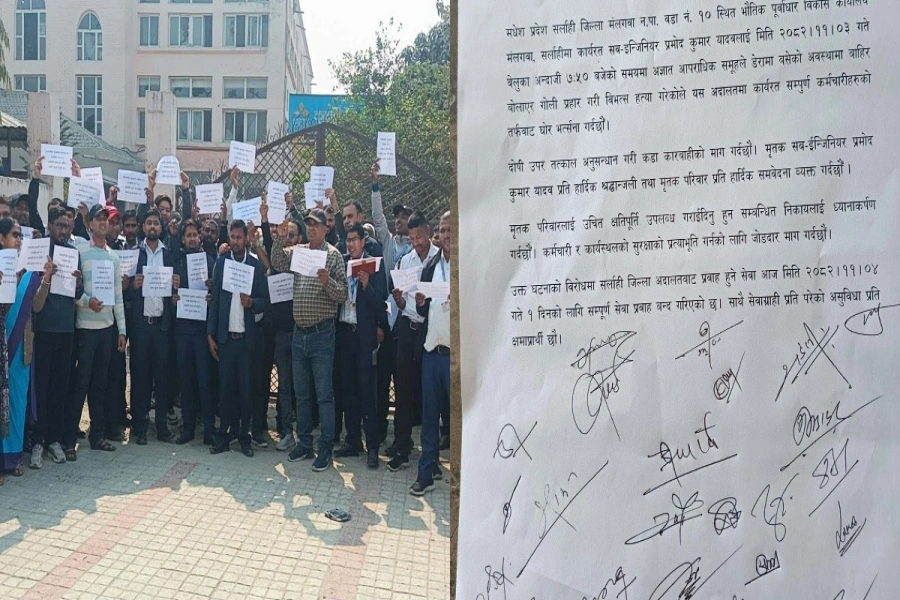

The alliance culture has forced voters to switch their voting behavior. A large number of votes were invalidated; this is because voters got confused by the electoral alliances or preferred to cross votes as a show of displeasure with the electoral alliances. When expectations were not matched by the electoral outcomes, alliance members grumbled over non-transfer of votes. This puts electoral outcomes in a shaky position post elections.

Many believe the rise of new and smaller parties like the RSP, RPP, Janamat Party and Nagarik Unmukti Party is due to the non-transfer of votes or voters betraying their loyalties. The RSP was successful in cashing the votes of frustrated, educated but unemployed, middle-class urban voters while the RPP was able to cash in on the pro-Hindu, anti-secular, anti-federal, pro-monarchy votes. Janamat Party in the country’s east and Nagarik Unmukti Party in the west were able to cash in on the Terai-Madeshi votes that could have gone to the JSP or the LSP. Either by design or by default, the arrival of new political parties has re-shaped the political landscape of the country.

Third, electoral alliances have turned out to be a marriage of convenience. Instead of political parties forming alliances based on party ideologies or even performance agenda, the sharing of power has become a primary theme. It is absurd to see the Nepali Congress – a liberal political party allying with a communist party like CPN (Maosit Center) and RJP or CPN-UML – a communist party allying with a pro-Hindu, pro-monarchy party like the RPP.

The alliance between the CPN-UML and the RPP-Nepal was exercised to such an absurd level that the Chairman of RPP-Nepal, Kamal Thapa contested the elections with the CPN-UML’s electoral symbol ‘Sun’. Obviously, the marriage of convenience is not expected to last long. This is like legitimizing a married partner to sleep with someone else.

Time to question

Forming a coalition government is very much a legitimate and desirable activity during a hung parliament situation. However, ex-ante electoral alliances primarily designed to fix the electoral outcomes are like illegal match-fixing activities. This is against the principle of competitive democracy. Therefore, it is time to question the relevance and legality of electoral alliances. Like in sports, electoral match-fixing needs to be made illegal and banned outright. If not, we need to review our mixed electoral system which, in fact, has produced “mixed up” electoral outcomes. Obviously, this includes banning the clowns from taking up positions in the Election Commission.