The mantle beneath Tibet has been torn into four massive pieces, according to a new computer model that gives an unprecedented glimpse at what's going on under the surface our planet.

Determining exactly what's happening so far underground isn't always easy, but can help in everything from predicting earthquakes to understanding how terrain evolves over time. But up until now, the layout of the Indian mantle that passes under the Tibetan plateau has remained largely a mystery.

The new research, by a team at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, uses a variety of seismic readings and other geological data to identify huge rips in the mantle that have left four pieces at different angles and at different distances from the original tear.

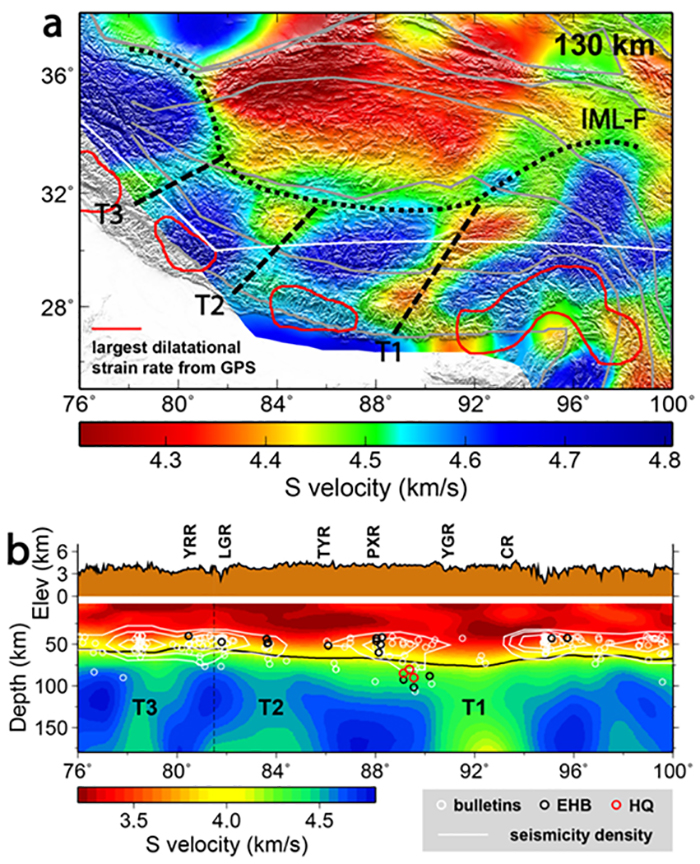

Seismic wave velocity images of the Tibetan Plateau (Xiaodong Song)

Seismic wave velocity images of the Tibetan Plateau (Xiaodong Song)

Conflict with the north

"The presence of these tears helps give a unified explanation as to why mantle-deep earthquakes occur in some parts of southern and central Tibet and not others," says one of the researchers, geologist Xiaodong Song.

We know that the Indian tectonic plate rammed into the Asian tectonic plate some 50 million years ago, kicking off a chain reaction of geological processes. What's less clear is how the land lies now.

When tears appear, it affects how much heat from the core of the planet reaches the mantle and crust, and thus how malleable it is – and how likely a large earthquake might be. Essentially, identifying these torn plate slabs in the new model could help save lives in the event of an earthquake.

Due to the topographical layout of the Tibetan plateau, carrying out studies of the terrain above and below ground is difficult. The researchers turned to seismic tomography, a way of mapping the ground at high resolution using energy waves – either produced by actual earthquakes or generated through controlled explosions.

The 3D model that was produced not only explains why some parts of the plateau experience stronger earthquakes than others, but also how a number of unusual north-south rifts on the surface were created. It also fits with historical long-term data collected by geologists on plate shifts.

"What were previously thought of as unusual locations for some of the intercontinental earthquakes in the southern Tibetan Plateau seem to make more sense now after looking at this model," says one of the team, Jiangtao Li.

"There is a striking correlation with the location of the earthquakes and the orientation of the fragmented Indian upper mantle."

Now the challenge is to use the new data to help assess earthquake risk in the future. While predicting an earthquake with any real degree of accuracy is largely impossible due to the limitless variables involved, having a rough idea of when and where quakes can hit means disaster recovery programs can be put in place.

That's where the geologists come in – studying the crust and mantle that we all live on top of for signs of movement and strain. Now that we have a much better idea of how the Indian mantle has been split up, future work can be carried out with much more accuracy.

"Overall, our new research suggests that we need to take a deeper view to understand the Himalayan-Tibetan continental deformation and evolution," says Song.

-69a940c05c766-1772700256.webp)