The second episode was the royal takeover of 1960, when democratically elected Government of Bishweshwar Prashad Koirala was replaced by king’s democracy under panchayat. The third episode was the brief period of people’s revolt in 1979 which forced the 1980 referendum on the choice between panchayat and democracy, which the panchayat side won.

The fourth episode came ten years later, in 1990, when widespread public uprising forced the king to dismantle panchayat and accept a ceremonial role under constitutional monarchy. Fifth, and latest of such episodes, unfolded in early 2006 when combined opposition from political parties and Maoist revolutionaries forced the king to give up power completely, followed by the constitutional end of monarchy two years later, in 2008.

All political transitions, including those Nepal has experienced, were upsetting and de-stabilizing but still considered justified on the ground that transitions signified change, which is ordinarily associated with progress and promise for a better life tomorrow.

Looking at our transitions from the perspective of a better life tomorrow, how have we performed—did these changes help improve public life? Did our transitions provide us with a hopeful outlook for the future?

Measuring the success of our transitions in terms of the quality of living, it looks as though we have maintained the status quo. However, if we are to look at it more objectively, most would agree that we have regressed backward. For example, we cannot be sure if the life of ordinary Nepalis today would have been worse-off if Rana regime had not ended, panchayat had continued, or king had wielded absolute power.

Such political continuity may have made a difference for a scant minority, but most people would have been content with whoever ruled the country. The point is, for a vast majority of the population, goings and comings of regimes made no difference which, unfortunately, created the basis for another cycle of uprising, instability, and change of regime, which justified yet another cycle of uprising and change of regime.

FALSE START WITH LOKTANTRA

Looking at the history of transitions, change in 2006 was for real and many times more profound and substantive than similar events of earlier epoch. Most significantly, the immediate source of danger to democracy represented by monarchy was removed and this paved the way for the assertion of people’s power, in the way that government can now be of the people, for the people, by the people.

Predictably, people recognized Maoists’ contribution to bringing this profound change in the system and voted overwhelmingly for them in the Constituent Assembly election in 2008, providing legitimacy for a Maoist-led Government to take the reigns of power. Unfortunately, Maoists misread the public mandate which was for moving the country toward peace and prosperity and much less for turning Nepal into a communist state and making it a center for international communism.

The emergence of messy politics, lack of government effectiveness, and erosion of public faith in the transitions we have had are due to confusion among the Maoists regarding who comes first: communism or people. In view of the communist debacle worldwide, the two goals together are incompatible and inconsistent.

COURSE CORRECTION NOW

Looking at the Maoists’ way of dealing with the country’s problems and handling of state affairs, it is apparent that Nepal’s struggle for democratization is not over yet. Similar to the difficulties democracy had faced in countering monarchy’s excesses, the same or a higher level of resistance to democratization is coming from Maoists, not for the reason that they are against empowering people but because their commitment to ideology prevents them from doing so.

And that ideology is for absolutism and authoritarianism, with no space left for people or institutions which can restrain them and provide checks and balances. Some degree of absolutism and authoritarianism may, at times, be needed as a measure of course correction but if such course correction is pursued for the promotion of a particular ideology—Maoism, for example—this can be outright dangerous and regressive.

However, labeling Maoists anti-democratic offers no solution to Nepal’s problems and, indeed, taking this route to countering Maoists would certainly be an invitation to catastrophe. An armed onslaught on Maoists, for example, has the potential to fracture the country, destroy civil society, and create an environment of unending upheavals and violence, which would benefit no one and hurt everyone.

At the same time, it looks impossible though, to motivate the people to go against Maoists, because the mainstream traditional parties calling themselves democrats have lost their credibility. In the eyes of people, democratic leaders are unprincipled and often crooks, compared to Maoist leaders who present a cleaner image and are capable of adhering to set principles.

It is inevitable and unavoidable then that Maoists must rule the country—there is simply no alternative to Maoists. However, in order for Maoists to be taken seriously to rule the country, they must make a credible offer to soften their position which basically means that the party must disavow communism. If it is not possible for them to give up on communism, it is hard to imagine how they would ever govern Nepal, even if they get a mandate for doing so, such as by winning a clear majority in parliament.

It is not the domestic opposition that would weigh down on Maoists—rather it is the international antagonism against communism, and the specter of isolation and neglect that would await a country daring to practice it. Add to this India’s outrage at seeing Nepal become a Maoist state and serve as a haven for its own Maoists.

GLUE THAT BINDS

It was probably alright for Maoists to adopt a revolutionary posture to help rid the country of an unpopular monarchy and feudal social structure. However, it is not appropriate that they continue with the revolutionary zeal past the revolution stage. The reason is that reconstruction efforts seldom succeed in an environment of lawlessness, fear, intimidation, and exercise of unchecked authority by revolutionaries. If this prevails, people get discouraged from taking responsibility and engaging in productive efforts, the loss from which cannot be offset by good intentions of government run by dictates and decrees.

Maoists must become an inward-looking force and not adhere to a foreign ideology quite irrelevant in Nepali context. Removing their ideological cover will help them re-focus their mission in a manner that promises concrete achievements by focusing on economic growth. If Nepal’s next door neighbors, India and China can have double digit economic growth rates, why can’t Nepal? If, somehow, Maoists can engineer this transition—from a decaying economy to a flourishing one—they will inherit the kingdom/country, because all previous regimes have failed at it.

Now, how are the Maoists going to create this economic glue that will bind people together—more strongly than monarchy ever did or Maoists can achieve through forced-indoctrination and coercion? There are a number of countries around the world where the only source of legitimacy offered to government has been their successful handling of the economy—Korea, Chile, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore are some examples. Admittedly, these countries had to set aside democracy for a while to give momentum to the economy. A case can then be made for Maoists to be forgiven if they choose to scuttle democracy for the sake of the economy, but has to be done in a transparent and credible manner.

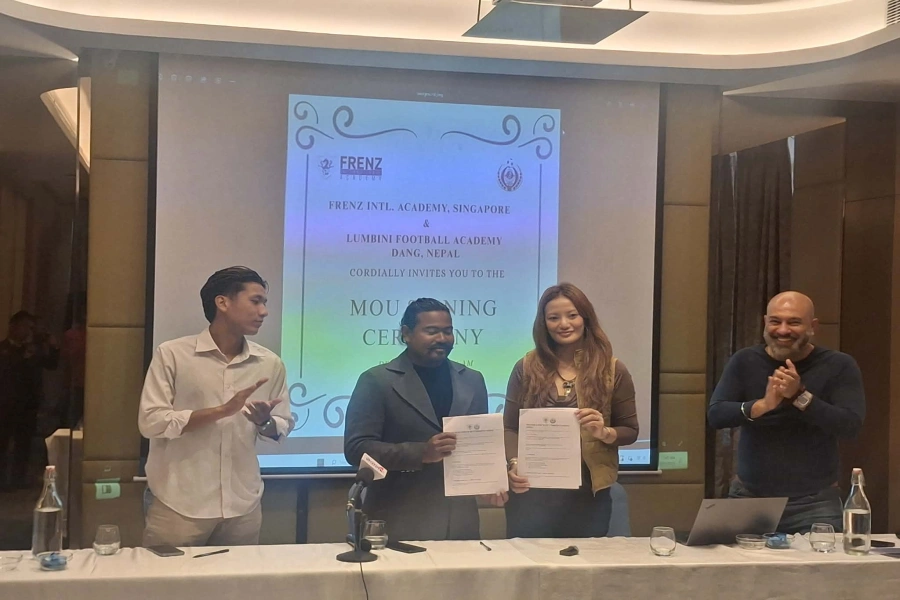

Nation marks 19th Loktantra Diwas today