DHAKA, BANGLADESH, Feb 5: Investigators from the International Criminal Court have begun collecting evidence for a case involving alleged crimes against humanity by Myanmar against Rohingya Muslims causing them to flee to neighboring Bangladesh, a court official said Tuesday.

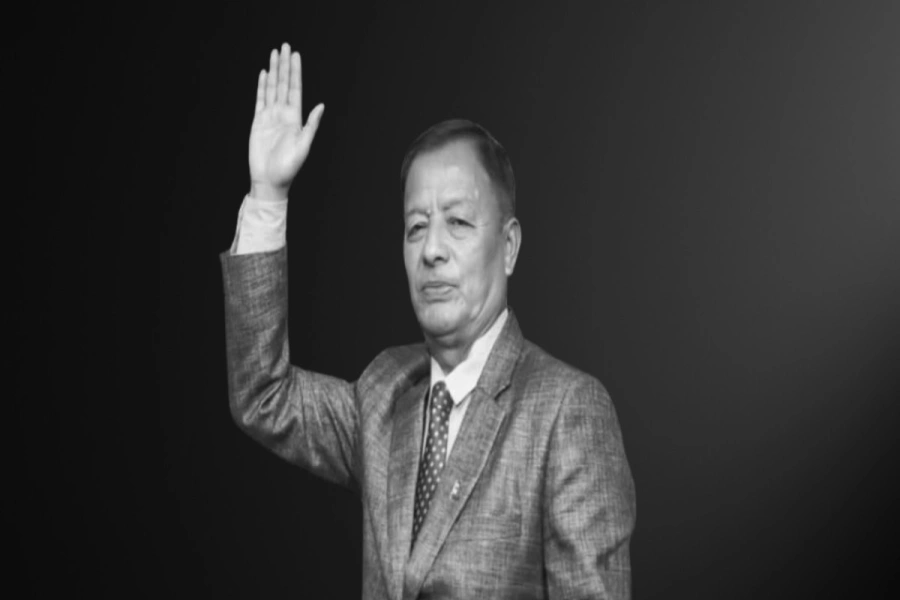

Phakiso Mochochoko, director of the Jurisdiction, Complementary and Cooperation Division of the ICC Office of the Prosecutor, said a team of investigators is visiting Rohingya refugee camps to collect evidence. He said justice will be delivered whether Myanmar cooperates or not.

Mochochoko told reporters in Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, that The Hague-based court will pursue the case even though Myanmar is not a party to the Rome Statute, the treaty that established it, and urged the Buddhist-majority nation to cooperate. Myanmar has denied committing crimes against humanity or genocide.

He said the court has a mandate to proceed with the case because Bangladesh is a party to the statute and the Rohingya crossed the border into that country.

He acknowledged that the investigation would be a long and difficult one without Myanmar’s participation.

World Court orders Myanmar to protect Rohingya from acts of gen...

“This is a challenge, we all agreed, it’s a challenge,” he said. “We have the experiences in the past, in some other situations where countries have refused to cooperate with us, they refused entry into their territory, but we have been able to investigate and prosecute the people.”

He said the investigators will talk to Rohingya refugees as well as witnesses in other countries.

Mochochoko said the investigators will work to identify who planned, facilitated and committed the alleged crimes.

“Investigators from the Office of the Prosecutor will now carefully and thoroughly seek to uncover the truth about what happened to the Rohingya people in Myanmar which brought them here to Bangladesh,” he said.

The responsible persons could be the head of state or other top people in Myanmar, he said.

Mochochoko said Bangladesh’s effort to start the repatriation of the Rohingya refugees would not be hampered by the ICC investigation and it can proceed to do so under an agreement it has with Myanmar.

He thanked Bangladesh for its support.

“As we undertake our independent investigations, we look forward to continued support and collaboration” from Bangladesh, he said.

He said the ICC is working in cooperation with the U.N.’s top court, the International Court of Justice, which ordered Myanmar last month to take all measures in its power to prevent genocide against the Rohingya.

The U.N. court said its order for measures to protect the Rohingya is binding “and creates international legal obligations” on Myanmar.

More than 700,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh after Myanmar security forces launched a crackdown on the Muslim minority in August 2017. Bangladesh currently houses over 1 million Rohingya refugees.

Myanmar has long claimed the Rohingya are “Bengali” migrants from Bangladesh, even though their families have lived in the country for generations. Nearly all have been denied citizenship since 1982, effectively rendering them stateless.

The International Criminal Court is a court of last resort that takes on cases when national authorities are unable or unwilling to prosecute alleged atrocities.