OR

Glimpses of the 50s, 60s and 90s

Published On: August 13, 2020 09:00 AM NPT By: Madan Kumar Bhattarai

Madan Kumar Bhattarai

Bhattarai is a former foreign secretary. He also served as the foreign affairs advisor to President Bidya Devi Bhandari during her first stint.news@myrepublica.com

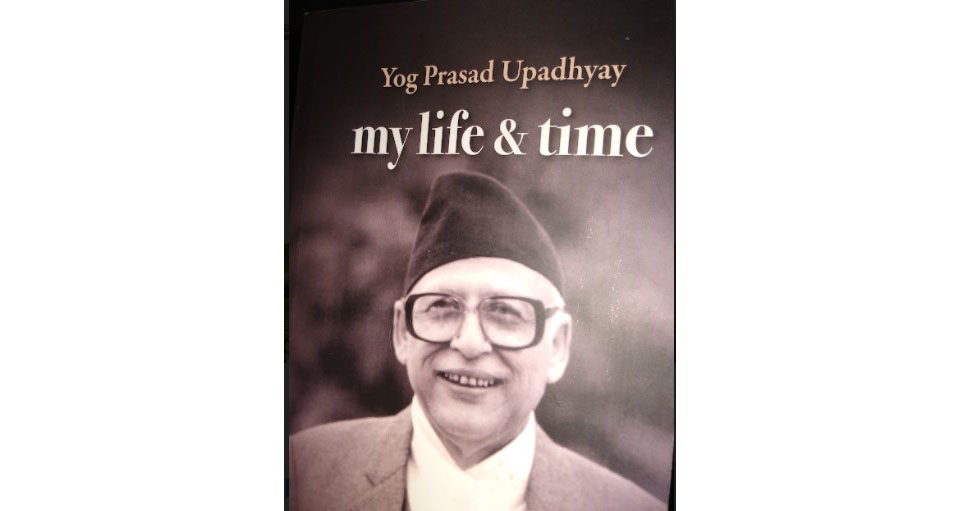

Yog Prasad Upadhyay’s “My Life &Time: An Autobiography” provides a picture of three important periods of Nepal’s history: Democratic movement of 1950, post-1960 systemic political change after dissolution of parliamentary system, and the change of 1990.

Yog Prasad Upadhyay’s My Life &Time: An Autobiography came out on February 26, his 94th birthday. Upadhyay is a person of several envious strands though known more as a political figure during at least three periods of recent political history of Nepal. These include 1951 democratic political movement, post-1960 systemic political change after dissolution of parliamentary system, and most recently the 1990 people’s movement restoring multiparty order. He is a man of stellar qualities and determination that he showed in plenty both as a bureaucrat and during his clandestine movement from Nepal to India after the 1960 political change.

Upadhyay basically remained a close ally, confidant and adviser of Krishna Prasad Bhattarai through thick and thin, and both on party basis as General Secretary and government as Home and Communication Minister. He even served as the ambassador to the United States as ostensible nominee of Bhattarai. It is a different story that the government led by the same party with Girija Prasad Koirala as Prime Minister took a summary decision to recall him prematurely, a recurring phenomenon in recent years in Nepal as ambassadorship is taken in our context as a sacrosanct “sovereign” decision to award all and sundry irrespective of merit, inclination, performance or even acceptance. In recent years, the system has degenerated into a game of trial and error of experimentation and all but diplomatic considerations are given in awarding people who are closer to party or person in power to the detriment of the country’s long-term interest.

Chemistry with Kishunji

Upadhyay rightly credits Kishunji, an affectionate term used for Krishna Prasad Bhattarai, for all positions he got in his long and eventful career—secretary, minister and ambassador. It is, therefore, in the fitness of things that the book has come out as a virtual tribute to mark the tenth anniversary of the demise of his mentor. There was no doubt that if any two political figures in Nepal can be said to have chemistry of thoughts and ideas, this fully applied in case of Bhattarai and Upadhyay.

One most important point to his credit is that Upadhyay is taken as a cerebral politician in contrast to many of his compatriots who are normally perceived in our case as everything but intellectuals. His clear conscience with a higher degree of integrity is proved by his decision to immediately tender resignation as minister, something unique in our case as we have a reputation of clinging to official positions, when he was bypassed without taking into prior confidence in appointing his junior colleague, Ram Chandra Paudel as Deputy Prime Minister.

From 1951 to 1960, Upadhyay was Deputy Secretary to the government and was soon upgraded to the level of Secretary. During this period, he had a stint as one of the first Fulbright scholars of the country having been to the United States for an academic course. He even played a role in the selection of officers for soon-to-be constituted Foreign Service with its own tortuous history of twists and turns, along with two other bureaucratic stalwarts.

They included Nepal’s youngest and most dynamic Foreign Secretary Narapratap Shumshere Thapa and fellow Secretary Pradyumna Lal Rajbhandary under whom Upadhyay had earlier served as Deputy Secretary. It is just not merely a matter of coincidence that the trio of Thapa, Rajbhandari and Upadhyay constituted a rarefied specimen of talent, integrity and leadership as top-ranking bureaucrats in Nepal, again an area that has now seen severe erosion in prestige, status, merit and performance.

Possibly for his closer ties with the party or important leaders in power as chief secretary of the Mahottari local government (Jana Sarkar), Upadhyay was always an important bureaucrat even as Deputy Secretary. This can be explained in terms of his role as convenor of regular conference of secretaries, something of a role played by cabinet or chief secretary after its eventual formalization in later years. He also took a momentous initiative to start Nepal Gazette as of August 6, 1951 as the official mouthpiece of government in terms of public decisions, appointments, notices and orders.

He was born in Shillong, earlier capital of Assam and now in Meghalaya of India, as his father Kewal Prasad Upadhyay Luitel migrated from Gorkha in 1916. Upadhyay’s life hovers around Assam, Benaras, Kolkata and Kathmandu, apart from his two stints in the United States, first as Fulbright Scholar and then as ambassador. The book makes an interesting account of Nepal’s contemporary political developments and impact of a largely four-party agreement involving King Tribhuvan, Nepali Congress, Ranas and Government of India.

This four-way political compromise, also called Delhi Settlement, paved the way for return of King Tribhuvan with full sovereign authority, continuation of Shri Teen Maharaj Mohan Shumshere as Prime Minister of the coalition government and end of Rana hereditary system, and entry of Nepali Congress and some other forces in the government. This is also the first of Nepal’s political experiments that ensured India’s abiding role in Nepal’s domestic politics.

The symptom seems to have continued unabated in one form or the other despite so-called indigenous manifestations of political changes our politicians may claim to have achieved in the poker game of endless constitutional and systemic changes in Nepal. Very often, there is a tendency to label people as pro- or anti-India.

From 1950 to 1990

The well-documented book details a first-hand account of developments in political scenario from 1950 onwards culminating in the assumption of power by Nepal’s first elected government led by BP Koirala, dissolution of party system and 30-year Panchayat rule, restoration of multiparty system and internal dynamics of Nepali Congress. While eulogising B P Koirala and Krishna Prasad Bhattarai, the author does not have much respect for first commoner Prime Minister Matrika Prasad Koirala. Likewise, the author also seems to have clearly second thoughts on aims, acts, intentions and motivations of Girija Prasad Koirala.

The book also gives interesting account of the diplomatic hoax played on behalf of the exiled Nepali Congress in the post-1960 scenario to embarrass the Nepal government by despatching a fake diplomatic mail to its embassies indicating a reconciliation between the royal palace and political parties. Soon it was uncovered and the government of Nepal alerted its limited number of missions that existed in those days. The book also evaluates the roles of many political figures both in the context of 1951 political change and government formation in Nepal.

While the book is a valuable addition in the list of English literatures on contemporary Nepali politics, it is regrettable that it abounds in mistakes on literal, grammatical and language fronts. Despite such technical weaknesses, I salute Upadhyay for his endeavours to bring out such a wonderful work even at such a ripe age that should act as a beacon of inspiration to many of his friends and counterparts. In terms of ambassador, Upadhyay is possibly the oldest surviving figure in Nepal except chief justice and Minister Anirudha Prasad Singh who served as our ambassador in Cairo in the sixties. In respect of senior secretaries, he is probably the oldest and even senior-most with the exception of Himalaya Shumshere.

The author has served as foreign secretary, ambassador and, most recently, as the foreign affairs advisor at the office of the president.

You May Like This

History not enough to retain party image: NC Leader Singh

SURKHET, June 9: Nepali Congress leader Prakash Man Singh has said glorification of party's history does not ensure its image... Read More...

History revisited

Exploitation of the country’s people and its riches truly took place during the continuous 105 years of Rana rule ... Read More...

Some glimpses of Gaijatra festival 2016

KATHMANDU, Aug 19: Today is the festival of Gaijatra. Nepali people, especially Newari community, are celebrating this festival with much... Read More...

Just In

- Nepal's ready-made garment exports soar to over 9 billion rupees

- Vote count update: UML candidate continues to maintain lead in Bajhang

- Govt to provide up to Rs 500,000 for building houses affected by natural calamities

- China announces implementation of free visa for Nepali citizens

- NEPSE gains 14.33 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.68 billion

- Tourists suffer after flight disruption due to adverse weather in Solukhumbu district

- Vote count update: NC maintains lead in Ilam-2

- NAC's plane lands at TIA after its maintenance in Israel

Leave A Comment