OR

The rise of radical ethnic nationalism as a response to fears of terrorism and mass migration represents a more fundamentally transformative crisis

TEL AVIV – This summer, Israel passed a controversial new “nation-state law” that asserted that “the right [to exercise] national self-determination” is “unique to the Jewish people” and established Hebrew as Israel’s official language, downgrading Arabic to a “special status.” But the drive to impose a homogeneous identity on a diverse society is hardly unique to Israel. On the contrary, it can be seen across the Western world—and it does not bode well for peace.

In the last few decades of rapid globalization, nationalism never really left, but it did take a backseat to hopes of greater economic prosperity. Yet the recent backlash against globalization—triggered not only by economic insecurity and inequality, but also by fears of social and demographic change—has brought a resurgence of old-fashioned ethnic nationalism.

This trend is reflected in and reinforced by what some experts call a “memory boom” or “commemorative fever”: the proliferation of museums, memorials, heritage sites, and other features of public space emphasizing links with local identities and history. Rather than celebrating diversity, people are increasingly eager to embrace a particular and exclusive identity.

In the United States, white people increasingly view the prospect that they will become a minority—a milestone expected to be reached in 2045—as an existential threat, and often act as if they are a disadvantaged group. US President Donald Trump capitalized on such feelings to win support, and his Republican Party is now relying on overzealous purges of “inactive” voters, stringent voter ID laws, and closures of polling places to make it more difficult for minorities to vote.

Meanwhile, support for the European Union’s enlightened values has eroded. Now, somewhat ironically, a grand alliance of right-wing nationalist parties has been established to improve their chances in the May 2019 European Parliament elections.

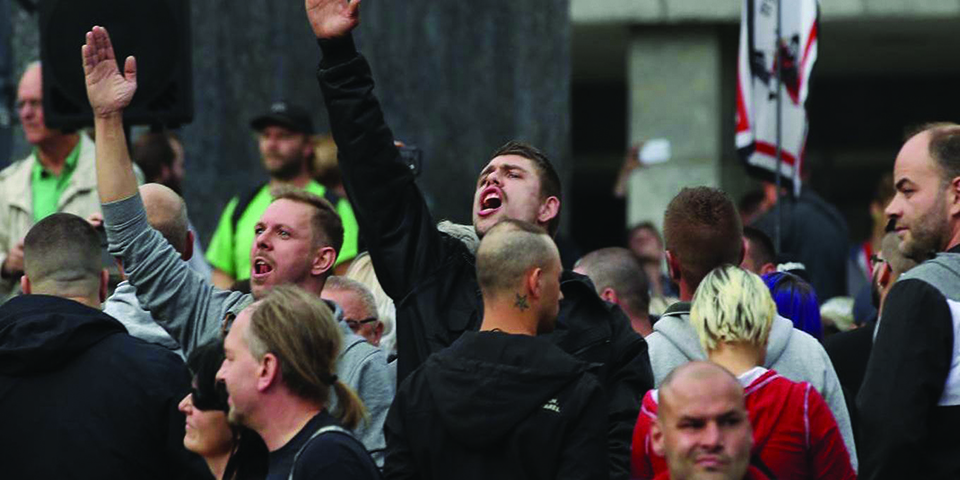

Such forces rail against “identity politics” (while speaking to predominantly white crowds who insist that they are their nation’s true representatives). This rhetoric has gained sympathy from some intellectuals on both the left and the right. Multiculturalism and international cooperation, authors such as Mark Lilla and Francis Fukuyama argue, turned out to be a fantasy of the liberal elites.

Similarly, the British philosopher John Gray, who has long decried “hyper-liberalism,” has attempted to turn the Brexit vote—a clear outburst of nativism and xenophobia—on its head. According to Gray, by pushing for a “transnational government” that most Europeans did not want, the EU was responsible for the rise of the worst kinds of nationalism. Resisting Brexit, he insists, would restore a “dark European past.”

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s anti-terror laws, enacted after the 2005 al-Qaeda-inspired suicide bombings in London, made him the first Western leader to repudiate so-called hyper-liberalism. Today, such repudiation can be seen across the Western world, from Trump’s administration and the “illiberalism” of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and de facto Polish leader Jarosław Kaczyński to Italy’s populist coalition government.

Ethnic nationalism like that enshrined by Israel’s nation-state law has long been a staple of politics in Central and Eastern Europe. Blood and religion, not citizenship, was what defined the nation during periods of subjugation. After the devastation of World War II, many of the region’s nations recovered sovereignty through large-scale ethnic cleansing.

Post-war European integration failed to resuscitate Central and Eastern Europe’s fin de siècle multi-ethnic dream. Instead, the ghosts of xenophobia and ultra-nationalism have been revived, exemplified in Germany by surging support for the far-right Alternative für Deutschland, which rejects post-war Germany’s expiations.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s enlightened refugee policies might thus turn out to be the last manifestation of Germany’s politics of guilt. Similarly, in Austria—which, to be sure, never admitted guilt in the first place—Chancellor Sebastian Kurz’s far-right, anti-immigration coalition is poised to end the EU’s politics of “identity annihilation.”

Western Europe was supposed to be free of ethnic nationalism. Modern nation-states were shaped along civic, not ethnic, lines, and the nation was defined as a community of citizens. Race, color, and gender were never supposed to be obstacles to full and equal civic participation.

Moreover, Western Europe is largely secular, whereas much of Central and Eastern Europe (not to mention the US) is more likely to link its identity to a religion-based moral order. Given these factors, in Western Europe, the rise of radical ethnic nationalism as a response to fears of terrorism and mass migration represents a more fundamentally transformative crisis.

This is all the more true of Northern Europe’s traditionally moral superpowers. The rise of the far-right Danish People’s Party and Sweden Democrats, with their roots in Swedish fascism and their nostalgia for the mythic white Sweden of the 1950s, amounts to a devastating blow to the most perfect model of social democracy that Europe has ever produced. The social-welfare state, the nationalists claim, cannot substitute for ethnic identity.

A recent study published in the journal Democratization shows that the overall level of liberal democracy worldwide now matches that recorded shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. There has been a “democratic recession,” as Fukuyama calls it, but it is concentrated in the more democratic regions of the world: Western Europe and North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Eastern Europe.

Given these regions’ importance to upholding the liberal world order, the rise of (white) ethnic nationalism has potentially serious consequences. Unless these countries devise a new way to balance liberal democratic values and people’s craving for a sense of belonging, they will end up paving a path to disaster.

Shlomo Ben-Ami, a former Israeli foreign minister, is Vice President of the Toledo International Center for Peace. He is the author of Scars of War, Wounds of Peace: The Israeli-Arab Tragedy.

© 2018, Project Syndicate

www.project-syndicate.org

You May Like This

On nationalism and populism

Nationalism is the highest priority for Nepal but our rulers and political actors are using and abusing it as the... Read More...

Unbreakable Nepal-India Relationship: Why Cracks Occur?

Nepal is an independent and sovereign nation and can manage its own internal affairs. However, from time to time, complaints... Read More...

State of real estate

How is it possible that land prices in Nepali cities with poor infrastructure are close to land prices in London,... Read More...

Just In

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

- Mahakali Irrigation Project sees only 22 percent physical progress in 18 years

- Singapore now holds world's most powerful passport; Nepal stays at 98th

Leave A Comment