OR

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken believes that Iran is only months away from being able to produce enough fissile material to build a nuclear weapon. Mitigating this threat and addressing Iran's broader destabilizing activities in the Middle East calls for a two-phase plan.

TEL AVIV – Former US President Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran utterly failed to enhance regional or global security. His successor, Joe Biden, must not make the same mistake.

The centerpiece of Trump’s Iran policy was his unilateral withdrawal of the United States from the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—widely known as the Iran nuclear deal – in 2018. This move, directly and aggressively promoted by Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, enabled the US to re-impose severe sanctions on Iran.

At the time, Iran was in full compliance with the JCPOA’s conditions, and it remained in compliance for a full year after Trump’s decision took effect, to give Europe a chance to uphold its pledge to bypass US sanctions. But Europe didn’t follow through, so Iran began to break the rules.

Now, as an outgoing deputy chief of Mossad recently noted, the situation is worse than it was when the JCPOA was signed. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken believes that Iran is only months away from being able to produce enough fissile material to build a nuclear weapon. If the country continues to raise limits imposed by the JCPOA, it could get there in “a matter of weeks.”

And yet, far from learning its lesson, Israel—together with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—wants Biden to maintain Trump’s failed policy. In January, Israel’s military chief, Lieutenant General Aviv Kochavi, warned the Biden administration against rejoining the JCPOA, even if its terms were toughened. He also announced that Israeli forces are stepping up preparations for possible offensive action against Iran this year.

For Iran’s neighbors, a US-Iran détente that does not address the Islamic Republic’s ballistic-missile program and support for proxies across the Middle East is a nightmare scenario. They fear that once tensions with Iran are defused, the US is likely to shift its focus away from the Middle East. The forthcoming Global Posture Review, now being prepared by US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, will likely reaffirm this prospect.

Against this background, it would be unwise to pursue French President Emanuel Macron’s suggestion that Saudi Arabia and other regional actors be involved in any new negotiations about the JCPOA. Of course, Saudi Arabia—which, along with the UAE, has demanded the Gulf states’ involvement—welcomed Macron’s call. But, as Iran recognizes, this is a sure route to diplomatic failure and the perpetuation of conflict.

Without these countries acting as spoilers, there is a chance of success. To be sure, domestic politics will limit Iran’s ability to accept changes to the original agreement. Years of devastating sanctions—together with America’s assassination of General Qassem Suleimani, Iran’s most powerful military commander, in January 2020 and Israel’s covert operations inside the country—have boosted Iran’s hawks, who performed strongly in last year’s parliamentary election.

In fact, days after the Suleimani strike, Iran launched missiles at US forces in Iraq, wounding more than 100 troops. Similar rocket attacks were launched this month, following US strikes on Iran-backed militias at the Syria-Iraq border. This, together with persistent attacks on Saudi Arabia by Yemen’s Iran-backed Houthi rebels, suggests that Iran has no intention of allowing the showdown over the JCPOA to hamper its regional power plays.

All great revolutions aspire to secure their legacy through expansion. For Iran, the imperative is to protect the Islamic Republic’s credibility not only among its citizens, but also among the proxies that channel its influence in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. That is why so many powerful voices in Iran will oppose returning even to the 2015 agreement: nuclear capabilities are regime insurance. The US doesn’t wage wars against nuclear powers.

Yet Iran has hardly shut the door on the JCPOA. On the contrary, it recently signaled its enduring willingness to compromise, by agreeing to hold for three months recordings from monitoring equipment installed at nuclear sites by the International Atomic Energy Agency. If the US rolls back sanctions within that timeframe, the recordings will be released. (Iran had previously decided that, unless US sanctions were lifted by February 21, intrusive checks of its nuclear sites would be banned.)

The Biden administration should use this window of opportunity to secure a straightforward agreement: the US lifts sanctions in exchange for Iran’s compliance with JCPOA restrictions on its nuclear activities. This would significantly bolster the moderate President Hassan Rouhani’s position vis-à-vis his hardline challenger, Hossein Dehghan, in this June’s presidential election.

But this would not be enough to mitigate the risk of a region-wide conflagration. For that, the US would have to negotiate a “phase two” agreement that addresses Iran’s ballistic-missile program and support for non-state actors across the Middle East, in addition to the JCPOA’s “sunset clause,” which would lift restrictions on Iran’s nuclear enrichment program after 2025.

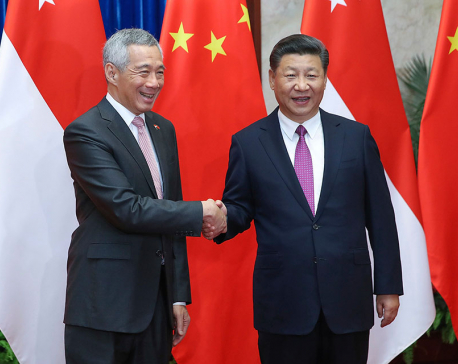

Given China’s massive investments in—and energy dependence on—the Middle East, it could be a useful ally in this effort. Already, China has proposed establishing a designated forum, in which Persian Gulf countries can address regional security issues, including compliance with the JCPOA.

There is reason to think that Saudi Arabia and the UAE—which, despite their large military budgets, cannot afford a full-scale war with Iran—would be willing to reach some kind of negotiated regional settlement within such a forum. As both countries set their sights on nuclear power, a non-proliferation scheme may also be a possibility.

Israel, however, would be excluded from this forum. In any case, it is highly unlikely to engage in negotiations with Iran. Responsibility for reining it in thus falls to the US. To that end, Biden should address Israel’s security concerns and expand the multilateral process to address Israel’s core strategic interests in Syria and Lebanon.

None of this will be easy. But a two-phase agreement is the best bet for the US, the region, and the world.

Shlomo Ben-Ami, a former Israeli foreign minister, is Vice President of the Toledo International Center for Peace. He is the author of Scars of War, Wounds of Peace: The Israeli-Arab Tragedy.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2021.

www.project-syndicate.org

You May Like This

China, Iran, North Korea seek support at U.N. to push back against unilateral force, sanctions

NEW YORK, March 12: China, Russia, North Korea, Iran and others are seeking support for a coalition to defend the... Read More...

America must mend many fences on trade

It is almost impossible to comprehend how much damage Donald Trump’s presidency has done to America’s global standing these past... Read More...

China protests US Navy sailing near South China Sea claims

BEIJING, Oct 11: China is protesting the sailing of a U.S. Navy ship near its territorial claims in the South China... Read More...

Just In

- World Malaria Day: Foreign returnees more susceptible to the vector-borne disease

- MoEST seeks EC’s help in identifying teachers linked to political parties

- 70 community and national forests affected by fire in Parbat till Wednesday

- NEPSE loses 3.24 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.36 billion

- Pak Embassy awards scholarships to 180 Nepali students

- President Paudel approves mobilization of army personnel for by-elections security

- Bhajang and Ilam by-elections: 69 polling stations classified as ‘highly sensitive’

- Karnali CM Kandel secures vote of confidence

Leave A Comment