OR

Democracy is the defense of Nepali sovereignty

Published On: January 6, 2021 08:30 AM NPT By: Dr Robert A Portada/Uttam Paudel

Dr Robert A Portada/Uttam Paudel

Robert Portada is an associate professor of political science at Kutztown University. Uttam Paudel is a graduate assistant at Pennsylvania State University. Their research on Chinese aid and investment strategies in Central America was published recently by the Journal of Chinese Political Science.news@myrepublica.com

While Nepali politicians remain motivated by personal gain, they have kept the great powers off balance. Nepal’s political uncertainties, and the record of multiple leaders shifting their priorities and relationships, have created difficulties for either great power to establish firm linkages with Kathmandu.

The borders of Asian countries have not been so fiercely contested since the Cold War. Great power interventions are scrambling Asia’s political geography. In the Himalayas, rising tensions between India and China threaten the smaller states perched precariously in the mountains.

Following its military occupation of Kashmir in 2019, India issued new national boundaries that included the Nepali territory of Kalapani. Another dispute over the Lipulekh border area raised alarms, while China expanded the scope of its border dispute with Bhutan.

Small countries situated among the great powers must raise defenses when nationalism is on the march and the memory of empire is reawakened. In such conditions, it is inevitable that great powers will seek to co-opt the small countries, so that functional sovereignty can be lost even when formal sovereignty remains.

Nepal finds itself particularly imperiled, positioned between the two Asian giants and adjacent to the 2100-mile-long Line of Actual Control. The June 2020 violence between India and China, their worst since the 1962 war, led to heavy reinforcements of troops on both sides. Amidst these intrigues, Nepal’s political system seems to have self-imploded. In December, Prime Minister KP Oli dissolved the lower house of parliament, forcing early elections set for April 2021. Irreconcilable personal ambitions within the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) set the stage for the constitutionally questionable move by PM Oli.

Even when housed under the same tent, the NCP has rarely had a unified agenda. A foreign policy document issued by PM Oli’s government just before parliament was dissolved reasserted a commitment to nonalignment while building a “multidimensional connectivity network” amidst the glare of Nepal’s great power neighbors. However, recent protests against corruption and calls for a return to the monarchy have produced widespread skepticism on the ability of any elected government to implement a coherent foreign policy.

What protections are left for Nepal? Political instability, the hallmark of Nepali democracy, seems to heighten its vulnerability. The calculus of power is in constant flux: Political upheavals are routine and coalitions are easily formed and readily dissolved. Indeed, no government has served a full five-year term. Even the KP Oli government, with its super majority in the House of Representatives, was left profoundly insecure. The loudest demands for the Prime Minister’s resignation consistently arose from his own party.

Nonetheless, the dysfunctions in Nepali democracy, including its pervasive factionalism and unstable rotation of leadership, also create obstacles to the great powers building the kind of lasting personal alliances that underpin imperial designs.

Nepali politicians have often courted foreign support to further their political interests. The NCP itself was formed from a coalition of rival factions competing to secure blessings from both India and China. The Nepali Congress, on the other hand, has historical ties with India, and the current leader Sher Bahadur Deuba also has a reputation for being friendly to the United States.

At times, the nationalist anti-India rhetoric of PM Oli makes him seem a reliable leader of the pro-China camp. However, the “surprise” meeting last October between PM Oli and the R&AW chief Samant Goel complicated this impression. Ignoring proper diplomatic channels, the intelligence chief arrived in Kathmandu as an “envoy” bearing Narendra Modi’s messages. Oli’s willingness to forgo protocols and face the inevitable backlash casted doubt on his nationalist credentials.

But the meeting was hardly a surprise. PM Oli and Sher Bahadur Deuba were both instrumental in ratifying the Mahakali Treaty of 1996, which was criticized for favoring India at Nepal’s expense. As PM Oli’s anti-India credentials were questioned, the NCP faction headed by Co-Chair and former Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal sought advantages. PM Oli might have earned Delhi’s trust for now, but he faced vocal criticism for his stance on Kalapani and remarks about the birthplace of Lord Ram.

While Indo-Nepal relations were somewhat strained during his premierships, Prachanda often supervised the ten-year Civil War from hiding in India, and cultivated deep relations with the Indian foreign policy establishment. Owing to his Maoist pedigree, Prachanda maintains cordial relations with Beijing. His shifting allegiances underlie his skills at playing Beijing and Delhi against each other.

Meanwhile, the Chinese ambassador in Kathmandu implored the NCP to remain united and resolve its internal differences, though the ambassador has also been the target of speculation for having undue influence on PM Oli. Likewise, in his highly celebrated recent visit, the Chinese defence minister General Wei Fenghe pledged to strengthen military and bilateral ties between Nepal and China. An absence of border disputes and China’s traditional policy of non-interference in internal Nepali politics have kept Sino-Nepal relations amicable, but the personal ambitions that led to the dissolution of the NCP highlighted the fact that Beijing has not yet established itself as the power broker in Nepali politics.

A new Cold War between China and the United States increasingly aligned with India raises new concerns about the threat of fresh clashes over territory and prestige. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has already targeted Nepal with massive infrastructure and capacity-building investments. However, India’s occupation of Kalapani and China’s occupation of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port show that strategically-located infrastructure projects are convenient precursors for territorial claims. China has clearly outpaced India in developing the region to its strategic advantage, a fact conceded by Indian commanders.

Embedding the interests of additional great powers in Nepal may preclude co-optation in this regard. The parliamentary ratification of the $500 million US grant from the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) has stalled, and is likely to remain so until new elections. A section of NCP leaders argue that the program is part of an American strategy to “contain China” and oppose a clause in the agreement stating it will prevail over existing Nepali laws. Though Nepal’s leaders should certainly reject any agreement that violates Nepali sovereignty, an amended agreement would balance China with an American presence, while allowing Nepal to benefit from Chinese trade and investment.

In the absence of a stable foreign policy, the messy factionalism of Nepali politics can protect the country from outright domination. Great powers prefer to extend their spheres of influence by fiat. A returned Hindu monarchy or a unified Communist Party would make ripe targets for India and China, respectively. While Nepali politicians remain motivated by personal gain, they have kept the great powers off balance. Nepal’s political uncertainties, and the record of multiple leaders shifting their priorities and relationships, have created difficulties for either great power to establish firm linkages with Kathmandu. To deepen democratic competition, the next generation of Nepali leaders should focus attention on organizing party structures independent of the patterns of corruption endemic to the prevailing political elite, while continuing the Nepali tradition of nonalignment. Institutional crises require the kind of participatory activism that improves and legitimizes democracy instead of undermining it.

A realist balancing strategy that draws the great powers closer is within reach. Such a policy would allow Nepal to lean toward one ally when others become threatening, and remain flexible in its relationships as threats ebb and flow. A more crowded space would decrease the freedom of action of the great powers. In the short run, this policy can be a smokescreen over Nepal's endemic political dysfunctions. In the long run, it can protect the last independent Himalayan state from being reduced to a vassal of its great power neighbors. Fortunately, the virtue of Nepal’s democracy is that it is just as difficult to co-opt as it is to govern.

You May Like This

Discussing Nepal’s geopolitical trajectory

Maintaining a delicate balance between the immediate and extended neighborhood is the best way for Nepal to realize its national... Read More...

The fault lines of Indian regionalism

Although India is competing with China by investing in connectivity in the region, it has not fully embraced economic openness.... Read More...

India turns to social-cultural ties as China steps up role in Nepal

KATHMANDU, Nov 26: As China tries to deepen its influence in Nepal through the overarching framework of its One Belt One... Read More...

Just In

- Nepalgunj ICP handed over to Nepal, to come into operation from May 8

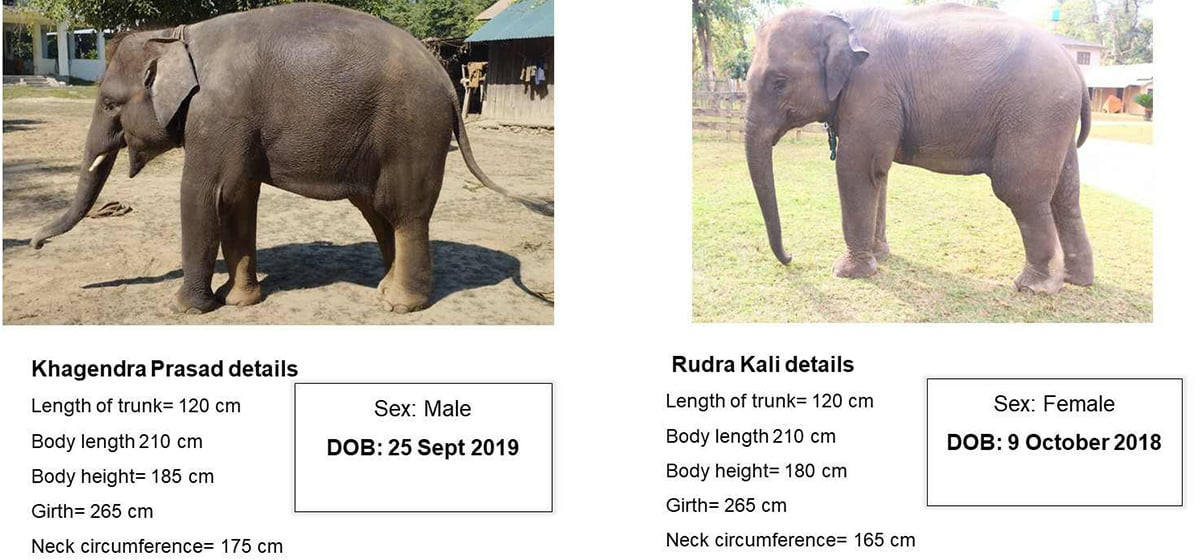

- Nepal to gift two elephants to Qatar during Emir's state visit

- NUP Chair Shrestha: Resham Chaudhary, convicted in Tikapur murder case, ineligible for party membership

- Dr Ram Kantha Makaju Shrestha: A visionary leader transforming healthcare in Nepal

- Let us present practical projects, not 'wish list': PM Dahal

- President Paudel requests Emir of Qatar to initiate release of Bipin Joshi

- Emir of Qatar and President Paudel hold discussions at Sheetal Niwas

- Devi Khadka: The champion of sexual violence victims

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment