OR

Bajura’s new mothers die young. Failure to give birth to a baby boy often results in second marriage

Published On: September 12, 2020 03:10 PM NPT By: Nanda Kumari Thapa

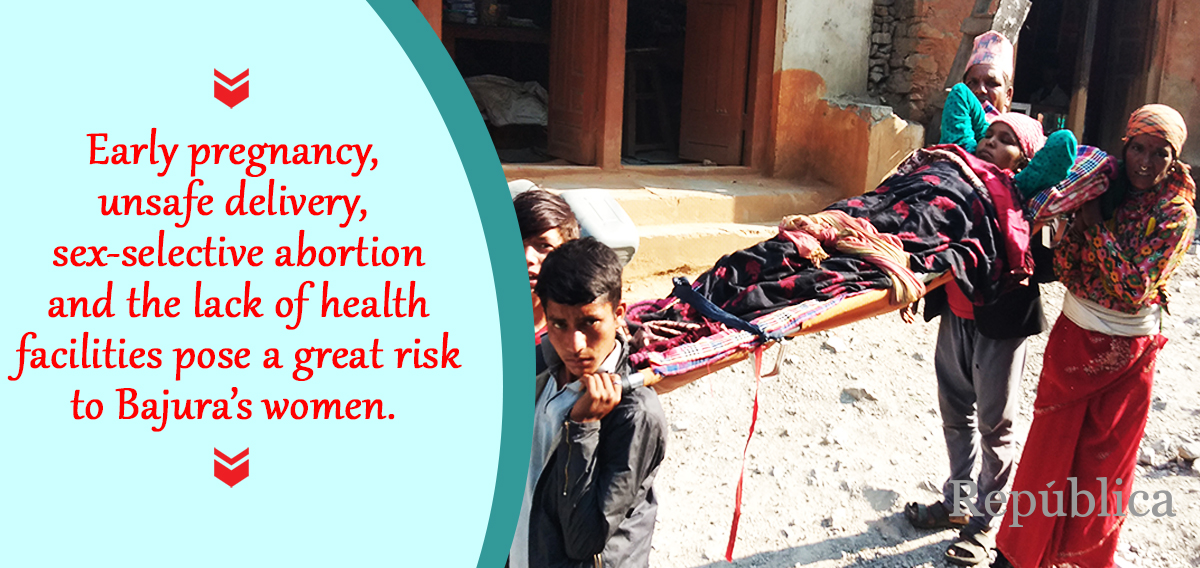

Early pregnancy, unsafe delivery, sex-selective abortion and the lack of health facilities pose a great risk to Bajura’s women.

According to Bajura District Hospital, three women had died of birth-related complications in the district in the fiscal year 2019/20. However, CIJ’s investigation shows that at least five women had died due to birth-related complications in that fiscal year.

Basanti Nepali, a local of Badimalika Municipality-7, was one among the five deceased women. She was the first victim of that year. On August 23, 2019, Basanti was admitted to Bajura Hospital after having delivery complications. Doctors later confirmed the baby was dead inside Basanti’s womb. The baby was taken out by using a vacuum extractor. An hour later, the mother also died.

Twenty days after Basanti’s tragic death, Nirmala Bohara, 35, from Budhinanda-10, Pandusen, also died in the same hospital. Nirmala gave birth to her last baby two years ago. “Her condition was normal when the dead baby was taken out from her womb by using a vacuum. But she died of excessive bleeding,” said Dr Durga Maharjan, who was involved in the delivery process.

This was the second birth-related death in the district.

On November 2, Rejiya Nepali, 37, died at Triveni Municipality-based Chhatara Health Post. Rejiya, a local of Bishal Bazaar, Chhatara, had reached the health office to give birth to her fourth baby. ANM Sumitra Padhya said she felt unconscious six hours after the delivery and died.

She was the third woman to die in the district.

Rejiya’s condition was normal when she was admitted to the health post. Her relatives had ferried her to the hospital around 11 PM and she had given birth to a baby two minutes after getting admitted. “Her condition was normal until 4 AM. She was unconscious after 5 AM and died,” Padhya said.

Without proper care, Rejiya’s baby also died in January.

On November 11, Kamala Ukheda of Budhiganga Municipality-7, Jhali, died in Chaukhutte, Achham, on her way to Dhangadhi for safe delivery. When Kamala was in labor, her father-in-law, Umi Ukhada, summoned a shaman and spent the entire day, believing that traditional magic would cure her pain. _20200912141753.jpg)

Parbati Gurung, 19, from Himali Rural Municipality-3 gave birth to a baby on her way to Lekkot, Assam in January 2019. This photo was taken in March 2019 when she was returning home.

Kamala was taken to Bayalpata Hospital, and she was later referred to Dhangadhi. “She died on the way to Dhangadhi Hospital,” said Dipak Shahi, health coordinator of Budhiganga Municipality.

And Pulti Rawal, 35, was the fifth victim. A local of Jagannath Rural Municipality-5 had given birth to a baby and was admitted to Gotri Community Health Center on November 25, following excessive bleeding as her placenta got stuck. Rawal’s relatives said that Pulti died on her way to the hospital.

But health officials said they had successfully removed her placenta. “Bleeding had stopped and she was basking in the sun. But she died suddenly,” said AHW Amar Budha, “Her baby is alive.”

Of the five dead, four had died at health centers--two at Bajura District Hospital, one at Chhatara Health Post and another one at the Gotri community center--and one died on her way to Dhangadhi in the hope of finding a better healthcare center.

Asked whether women are dying at childbirth due to the lack of resources, Tek Bahadur Khadka, health coordinator at Badimalika, says the number of deaths reflects ‘the level of awareness in Bajura.’

“Very few come for regular checkups. Women are not taken to the hospital for a delivery service. And there is a lack of rest and nutritious food during pregnancy--the critical period for women.”\

_20200912142003.jpg) Budinanda Municipality-9, Bajura's Purna Damai feeding Lactogen to her malnourished son at the district health center in Bajura. Of Damai's 13 children, seven are alive today.

Budinanda Municipality-9, Bajura's Purna Damai feeding Lactogen to her malnourished son at the district health center in Bajura. Of Damai's 13 children, seven are alive today.

Patriarchal mindset

On average a woman in Bajura gives birth to five to seven children. Some of them have given birth to 12 to 15 babies.

Purba of Budhinanda-1 gave birth to 13 children. Of them, one son and six daughters are alive. “I gave birth to many children hoping to have at least a son. Initially, I breastfed my baby. But I stopped because my milk dried up. Purba said she never used birth control contraceptives.

Aawarma Budha, 42, of Swamikartik Rural Municipality, who had married at 15 gave birth to her 13th baby last year. Of them, nine--seven daughters and two sons--were born alive and four died while giving birth. With the exception of her last baby, Aawarma gave birth at home, said Payan Budha, her husband.

Chhamma Luwar, 45, of Jagannath Rural Municipality-4 has just given birth to her 11th child. Of them, seven are alive. She had married at 11.

“Women have to face abusive words if they are unable to give birth to at least a boy. Many children were born in hope of getting a son,” said Chhama.

The story of Kushukala Sarki, 41, of Jagannath Rural Municipality-2, is not different from other women. Recently, Kushulal gave birth to her twins, her 10th children at 41. Her health condition is bad.

Dharma Rokaya, a staff nurse at Bajura Hospital, said women in Bajura’s remote villages give birth to at least two to three children in their 20s and continue to give birth until the age of 45 or the time when menopause starts.

“Many women give birth until their life is at risk,” said Rokaya adding, “Thus, children can be at greater risk of disability, malnutrition, mental complications. Children’s health remains at risk whereas the mother may lose her life due to excessive bleeding.”

Women in Bajura feel ignored, humiliated, and stressed unless they give birth to a baby boy. Kalpana BK of Badimalika-9 is one of the countless women facing mental torture for failing to give birth to a son. She has already given birth to six daughters, and the youngest one is six-month-old. Her family wants her to give birth to a son. “My husband has threatened to marry a second wife if I fail to give birth to a son. I often want to cry when I recall the abusive words of my neighbors.”

A pregnant woman from Sapaatta, Swamikartik Ruralmunicipality, being taken home after getting herself checked at the Kolti Primary Health Post.

Sex-selective abortion

Many women undergo cycles of selective abortion with the hope of giving birth to a baby boy. Laxmi*, a woman from Budhiganga Municipality-10, Sigada, underwent eight cycles of sex-selective abortions. The first and second abortions didn’t affect her health. But she almost died when she had her third abortion, which caused excessive bleeding. Her family had to take her to India for treatment.

Chandari* of Himali Rural Municipality-6 in Bajura has a similar story. Chandari was admitted to the hospital for critical care after she aborted several times in the hope of giving birth to a son.

Women from hilly villages of the Far-western region go to Indian private hospitals to identify the sex of their child shortly after getting pregnant and they later abort child in Nepal if a daughter is conceived. Dhauli*, a woman from Badimalka-7 Kordha, identified the sex of her baby in Paliya of India and bought medicine worth Rs 1500 from a Bajura-based medical store to abort the fetus.

She suffered excessive bleeding. She was then taken to Bajura Hospital which later referred Dhauli to Bayalpata Hospital. She survived but her health is not good. As per Safe Abortion Service Expansion and Work Operation Service Guideline-2066, both the person and organization willing to provide an abortion service need to obtain a certificate from the Department of Health Service and Family Health Division. But unskilled persons have been handling abortion in Bajura’s remote villages.

“Although several organizations have been working against discrimination, our society hasn’t changed much. That’s why selective abortion is rife—a stark case of gender discrimination, said Rukmani Shah, president of Women’s’ Right Forum, an NGO.

Shah said husbands often marry a second wife, family members expel women and even the society humiliates women if they fail to give birth to a son. “They opt for sex-selective abortion as we have several cases of discrimination where the husband has married a second wife and women are expelled from homes for not giving birth to a son.”

_20200912142323.jpg)

Kalpana BK, from Badimalika Municipality-9, along with her four daughters.

Young mothers

Giving birth on the way is to a healthcare center is common in the mountainous villages of the Far-western region. Rama Gurung, 24, of Himali Rural Municipality gave birth to a baby boy in the middle of a forest in Achham in November 2019. “I gave birth to a son on our way to Devisthan of Achham. Except for my husband, no one was with me, so I was forced to stay under a make-shift tent,” said Rama.

Like Rama, Sita Thapa Bhote of Tajakot-2, Humla, gave birth to a daughter while she was staying under a make-shift tent near Rida Bazaar of Bajura. “I gave birth to a baby on my way to Bajura. I then went to a doctor and returned home.”

Ramit Budhathoki, 23, of Sarkideugaun in Humla said that she “can't take rest and I have to carry heavy loads, cook food and do other words”.

Buddhi Bogati, a former district chairperson of the Federation of Indigenous Bhote Community, said most women give birth to babies on their way as they have to migrate to lower lands for six months to avoid cold. Such seasonal migration is common in Bajura, Bajhang Mugu, Humla, and Jumla districts of Sudurpaschim and Karnali Provinces.

According to the national census of 2011, 24,919 girls had married before the age of 20, the legal age set for marriage. Of them, 4,000 girls had married before 15.

A record compiled by the Bajura Health Office shows that 592 pregnant women aged below 20 came to the office in the fiscal year 2017/18, 486 in the fiscal year 2018/19, and 451 in 2019/20. “These are just a number of women with early pregnancy who approached us, but the actual number could be higher,” said Rugam Thapa, district health chief.

Haliya women suffer the most

Haliya system is a horrible tradition in Sudurpaschim, where a well-to-do family keeps a tenant as a slave for life for a small sum of loaned money. Even as the government outlawed the Haliyas system in September 2008, there is no change in their socio-economic status. The health condition of Haliya women remains poor.

Ghiru Luwar, 65, of Budhinanda Municipality-1, Pipaldanda is a representative case of this community. Ghiru gave birth to seven children and is now suffering from acute lower stomach ache. “I've been suffering from lower stomach pain since I gave birth to my third child. We don’t have enough money for food, how can I get money for treatment,” said Ghiru, whose husband works at a local money lender’s house to feed their children.

There are about 1,700 freed Haliya families in Bajura, but the District Administration Office has recognized only 1,300 households. Economically poor, freed Haliyas suffer the most. “Most women live with their disease. Daily wage earner Haliyas hardly have enough to feed their family members. Local health offices cure only minor diseases. Our wife, mother, sister can't go to Dhangadhi, Nepalgunj, and India for treatment,” said freed Haliya Jayamal Luwar.

Deuma Dhami, who works at Kolti Primary Health Post, said most Haliya women have been suffering from uterus prolapse and lower stomach pain.

Bisra Luwar, a Haliya woman says she has not been able to get medical care due to financial troubles.

Lagging in SDG target

Dr. Rupchandra Bishwokarma, chief of Bajura District Hospital, says uterus prolapse is common among young mothers and those women who have many children or those continuing to give birth until menopause. “This shows family planning programs are still ineffective in remote villages,” said Dr. Bishwokarma.

The poor socio-economic condition of the people living in Bajura has had a deteriorating effect on the health of the women. Human Development Report-2014 ranks Bajura as the poorest district among Nepal’s 77 districts.

Dr. Bikas Devkota, a former spokesperson at the Ministry of Health and Population, primarily blames delays in admitting to a hospital, delay in getting a vehicle to the hospital due to poor economic status and the unavailability of vehicles, and delays in getting services at the hospital.

“To achieve the SDG target, we have to reduce maternal mortality per 100,000 live births to 70 by 2030. It appears we are not in a position to meet the target,” said Dr. Devkota.

*Names have been changed to maintain privacy.

Prakash Singh contributed to the reporting. The story was produced with support from the Center for Investigative Journalism-Nepal

You May Like This

NOC slashes price of petrol by Rs 7 per liter, diesel and kerosene by Rs 5 per liter

KATHMANDU, May 15: Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC) has announced a significant reduction in the prices of petrol, diesel and kerosene. Read More...

Are We Prepared?

Bajura earthquake serves as a reminder that earthquakes can strike at any time and we must always be prepared. ... Read More...

What Nepal needs is India's friendship and support for growth: Nepal PM Oli

In an exclusive interview to The Hindu, Mr. Oli says the bitterness of past relations have been put behind them,... Read More...

_20200912142435.JPG)

Leave A Comment