OR

More from Author

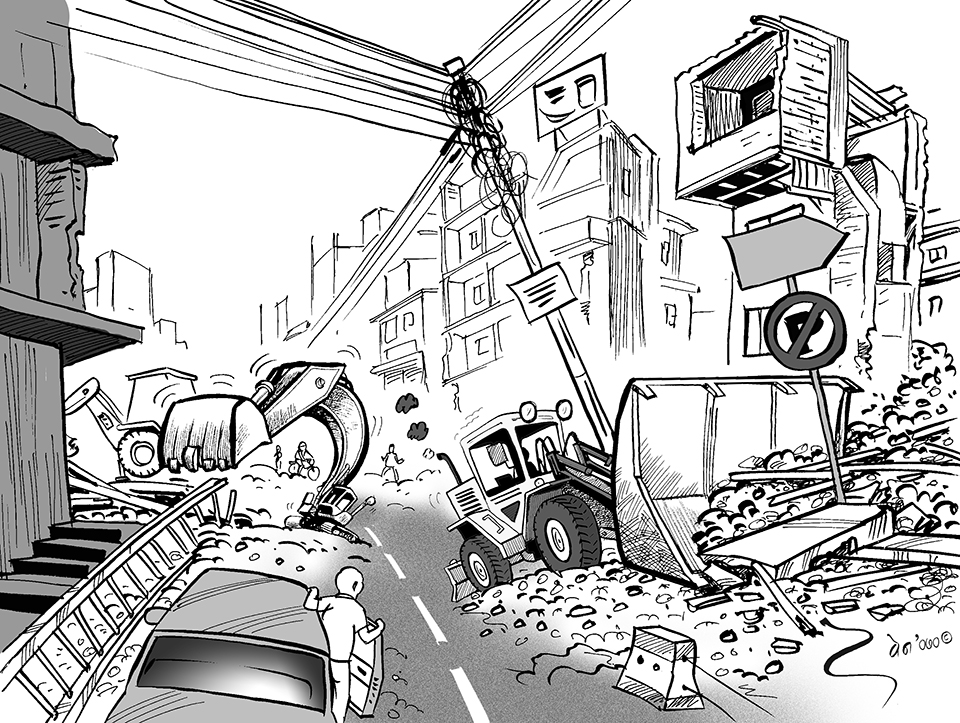

It is unfortunate that while elsewhere in the world people are advocating for ways to create walkable neighborhoods, we are bulldozing our already existing footpaths.

When I first went to my urban planning classes, I imagined that city planning would entail designing wide streets, chic modern concrete houses and making room for lots of cars. It was quite opposite to my expectations. My professor insisted that one of the main reasons the downtown Detroit’s failure to attract enough people after the major games in Detroit Stadium is the high-speed highway right in the middle of the downtown.

Furthermore, he was adamant in his argument that the street speed is one of the main factors in the demise of the downtown in most of the decaying US cities (and there are a lot). Many scholars see American highway as the main culprit of demise of American socio-cultural life especially African Americans. He often gave the example of Ann Arbor and its booming downtown and cited the narrow low speed streets, and well connected side and walking streets (I went to do my urban planning degree in Michigan where Ann Arbor and Detroit is. Detroit is the foremost example of a decayed city and Ann Arbor is booming small University town). In Ann Arbor, they have passed the law that street belongs to pedestrians and all vehicles have to let the passer-by walk at all times.

Case of Kathmandu

Kathmandu is undergoing a large scale of street widening program since 2011. Now, we are in 2017, and the result is the biggest public health crisis as the most polluted city in the world (177th out of 178). The effect of air pollution can range from irritating eyes, throats, allergies, to the lung cancer, brain damage, heart attack and central nervous system failure. The list goes on. Most of the air pollution in Kathmandu is the consequence of these street widening feats. Apart from that, Keshav Sharma and Kalpana Adhikari, in their ring-road series Setopati article had rightly pointed out the design deficits and incongruencies of the Kalanki-Koteshwar road. Their major concerns are the road is not safe and convenient for pedestrians, it has no enough traffic light, zebra crossing, no median and no bike lane.

Jane Jacobs said “streets are the blood vessel of the city and safety of the city comes with the safety of the street.” Jane Jacob is the most powerful thinker of modern urban planning. Her name is revered in urban planning literature as the one who revolutionized the urban planning. Her work and ideas have been so influential that when a planning problem occurs, it is common for individuals to ask: “What would Jane Jacobs do?” Her enduring ideas became the building block for generating new ideas in city planning. After meeting Jane Jacobs, Adam Gopnik, New Yorker writer said that Jacobs had the aura of sainthood. “Jane Jacobs’s aura was so powerful that it made her, precisely, the St. Joan of the small scale. Her name still summons an entire city vision—the much-watched corner, the mixed-use neighborhood.”

She wrote her most popular book The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961 as a critique to the contemporary American urban planner. The book has created a phenomenal vision for a vibrant city as well as the strategies that are needed to fulfill this vision. She argues that cities are not merely a set of infrastructure thrown together but an interwoven mess of intricate and delicate socio-spatial relationships. The book is very relevant for Nepal, as we are in the crossroads of making choices for creating a new vision for our cities especially for our streets. Do we want to blindly follow the-donor-led monstrous mindless concrete developments or we want to pause and think about restoring our ancient-heritage city?

Streets for safety

Jacob argues that major function of the street is safety of the pedestrians. Streets and their sidewalks, the main public places of a city, are its most vital organs. If a city’s streets look interesting, the city looks interesting; if they look dull, the city looks dull. Jacob’s dream city is just the opposite of traditional planners’. She aims for a community that is full of life and has a strong sense of safety. Thus, she advocates that the streets, sidewalk and park should be full of diverse people at diverse times. She observes the various functions between individuals and neighborhoods with its streets and parks, minutely analyzing what goes on in a lively or safe street and what happens in a deserted and lonely street. To keep the street safe, she argues, one needs to have an eye on them continuously and must have multiple users at multiple times. She describes the ‘ballet of sidewalk’ where different people do multiple activities resulting into a never-ending dance of human chores that breathe the life into city airs. In the midst of all those continuous hummings of the activities in the sidewalk, no one feels unsafe or threatened. Children of the neighborhood play with each other. They are continuously monitored by the eyes of passerby, shopkeepers, and strangers and are safe. Similarly, people in parks will be safe at all times whereas an empty park will be a habitat for thugs.

After reading the book, I was convinced that she had been to Thamel or Basantapur of Bhanubhakta’s time when Kathmandu was dreamy Kantipuri Nagari. Most of Jacob’s ideas are already implemented in the design of our cities in Kathmandu, Patan and Bhaktapur by our ancient city planners. As I was reading about Jacob’s ‘ballet of sidewalk’, I had my reminiscence about Jawalakhel or even Asan. If you stand in the little square of Jawalakhel and look around, you can see incredible varieties of buildings and uses. For example, there are small family run ethnic restaurants and food courts where we can eat really low-priced foods. And, there are exclusive and expensive restaurants for tourists. There are small computer workshops, boutiques, groceries and hardware shops in the old buildings. Similarly, there are numerous training centers, language centers, bicycle repairs in old buildings and next to them, there are chic new buildings for airline offices, banks and modern equipments. It has school buildings, hospital and pharmacy next to each other. It even has a zoo next to football field where you can go for a walk. The street is never empty and the place is brimming with life at all times in every season. People’s livelihood literally depends on the streets. I am worried that widening street mania would destroy our social fabric and will turn our street unsafe for residents like Usha Basnet, a resident of Sanepa Satmarga. She had lost the footpath at the front of the house in one of the street-widening madness (as reported by Chetna Guragain in Setopati).

It is so unfortunate that everywhere else in the world people are advocating and changing their ways to create walkable neighborhoods and we are bulldozing our already existing footpaths. People are calming their traffic by creating speed humps, street-side parking, paving the zebra crossing. We are increasing the speed. Many specialists and urban planning researchers have argued that street widening is never the solution. We need to look for innovative alternative solutions to manage our streets. Creating the impervious surface has other hazards such as stormwater-management and groundwater depletion problem as well as waterbody pollution in the nearby streams. Thus many cities in the United States advocate the management of rainwater where it falls by creating pervious surface options such as paver stones and bricks.

Netherlands lessons

Even if we want to emulate developments from other countries, why emulate from the countries like China and the United States whose souls are motivated by the greed? Both countries have rampaged environment in the name of development and both have most dead streets in the world. Why not copy the Scandinavians and their way of development? Why not emulate Netherlands to be specific? There are more bicycles in Netherlands than residents and 70 percent of all journeys are made by bikes. During the 70s, when the automobiles filled the streets of Netherlands, the killing of its resident upsurged which led the Dutch to build safe and vast network of cycle path.

They have built the bike path and parking facilities everywhere. In less than two to three decades cycling has become the integral part of Dutch life, which is a win-win for everybody. Needless to say, cycling is good for health, for air and good for streets. And it is cheap. Instead of widening roads, why not create aesthetic, pleasing and safe bicycle paths that would integrate with our ancient well-thought city planning?

You May Like This

Alternative route for trekkers in Mustang

MUSTANG, May 8: The local administration decided to close entry to the general public to the Muktinath temple premises from... Read More...

Alternative to Narayangadh-Mugling road identified

CHITWAN, Oct 5: Alternative to the Narayangadh-Mugling road section has been explored considering the growing traffic and the difficulties in... Read More...

No alternative to Dasharath Stadium for SAG opener: Bista

KATHMANDU, July 16: National Sports Council (NSC) Member Secretary Keshab Kumar Bista on Friday said that the opening ceremony of... Read More...

Just In

- DoFE requests relevant parties to provide essential facilities to foreign workers traveling abroad

- Foundation stone laid for building a school in Darchula with Indian financial assistance

- 151 projects to be showcased for FDI in Third Investment Summit

- Police disclose identity of seven individuals arrested with almost 2 kg gold and more than Rs 10 million in cash

- NIMSDAI Foundation collaborates with local govt for Lobuche Porter’s Accommodation Project

- Home Ministry directs recalling security personnel deployed for personal security against existing laws

- Fake Bhutanese refugee case: SC orders continued pre-trial detention for seven individuals including former DPM Rayamajhi

- ADB Vice-President Yang pays courtesy call on PM Dahal

Leave A Comment