OR

BEYOND BORDERS

Biswas Baral

Biswas Baral has been associated with Republica national daily as a journalist since 2011. He oversees the op-ed pages of Republica and writes and reports on Nepal's foreign affairs. He is a regular contributor to The Wire (India).biswas.baral@myrepublica.com

More from Author

China apparently has the best interest of Nepal at heart, while India is forever scheming to undermine our sovereignty and territorial integrity.

There is this tendency, much pronounced after the 2015/16 border blockade, of seeing China as Nepal’s great savior. In this thinking, India, the old big brother, is Nepal’s sworn enemy, and nothing it ever does will be in Nepal’s interest. On the other hand, China, which has never tried to unduly meddle in Nepali politics, or to in any way imperil our sovereignty of late, is almost seen through rose-tinted glasses. It can seemingly do no wrong. This is a dangerous belief.

This tendency is also evident in the current India-China standoff over Doklam plateau, their tri-junction point with Bhutan. The decision of the Indian army to intervene, on Bhutan’s behalf, and stop China from building road in the ‘no-man’s land’ between Bhutan and China, is being seen in Nepal as yet another proof of India’s big brotherly attitude to its small neighbors: Why did India have to force itself into what was a purely bilateral issue between Bhutan and China?

It does not help India’s image in Nepal when it is seen occupying around 600 square kilometers of Nepali lands at various border points. China, meanwhile, settled most of its border disputes with Nepal back in the 1960s, even with concessions, and currently occupies no Nepali territory. This, again, apparently shows that China has the best interest of Nepal at heart, while India is forever scheming to undermine Nepal’s sovereignty and territorial integrity—much like it is now unduly coercing Bhutan into not maintaining any relations with China. If only things were as straightforward.

Statement of purpose

If we read the statement of the Bhutanese foreign ministry on Doklam incident, it clearly says that Bhutan has conveyed to China “that the construction of the road inside Bhutanese territory is a direct violation of the [old] agreements”. Bhutan hopes, the statement continues, “that the status quo in the Doklam area will be maintained as before 16 June 2017”.

In plain-speak, China has no business building in no-man’s land and Chinese troops must retreat to restore status quo ante.

Of course, it might be argued that India pressed the Bhutanese into issuing the statement, which is possible. It might even be true that many Bhutanese are in favor of closer ties with China. Moreover, China would perhaps have not used force had India not foiled, and repeatedly, its more straightforward attempts to establish diplomatic ties with Bhutan.

Yet if India blockading Nepal to achieve its self-serving goals is unjustified, how can China’s use of force on another small country in the same neighborhood, and for a similar purpose, be justified? Xi Jinping and PLA minders knew perfectly well that their building spree so close to India’s strategically important chicken neck corridor would draw a response from India. In other words, Beijing was sending a message to New Delhi that China will not desist from using force if that is what it takes to achieve its foreign policy objectives in South Asia.

That should not be a surprise. Historically, unlike the Europeans and the Americans of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Chinese have been reluctant to colonize and rule over distant lands. But it’s a different story in China’s near abroad. Just as India thinks of the ‘Indic’ South Asia as coming under its sphere of influence, China has historically seen ‘Sinic’ Southeast Asia as falling under its sphere. China’s relations with Southeast Asian countries like Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam have thus been similar to India’s relations with South Asian countries like Nepal and Bhutan. The allegiance of most Southeastern countries locked in, China is now looking to spread into another important part of its near neighborhood: South Asia

Don’t get me wrong. I am still firmly in favor of greater engagement between Nepal and China, which is important to offset India’s often-domineering presence in Nepal. I also think Nepal did the right thing by signing up for the OBOR framework agreement. Besides ensuring greater links between Nepal and China, Nepal’s entry also sent an important message to the outside world: that Nepal is capable of acting independently of India in its foreign relations.

Other face of Janus

Yet the Doklam incident, in many ways, also showed China’s ugly face. Some of the commentary and editorials that have appeared in Global Times, the Chinese Communist Party mouthpiece, on Doklam openly threatened India with another humiliating war. Not only were they in poor taste, the openly hostile and coarse language also betrayed a sense of insecurity. It appeared that since China’s position in Doklam was indefensible, it was trying to browbeat the rest of the world into believing its anti-India propaganda.

If China is ready to use force in Bhutan today, what is the guarantee it won’t do so in Nepal tomorrow? But why would China use force on Nepal, right?

Just like ‘roti-beti’ relations with the southern neighbor and India’s democratic character are often exaggerated, mostly to India’s benefit, we are in risk of doing something similar in the case of China when we invoke its ‘inherently benevolent’ character. But china is just another country in the comity of nations, with its own interests.

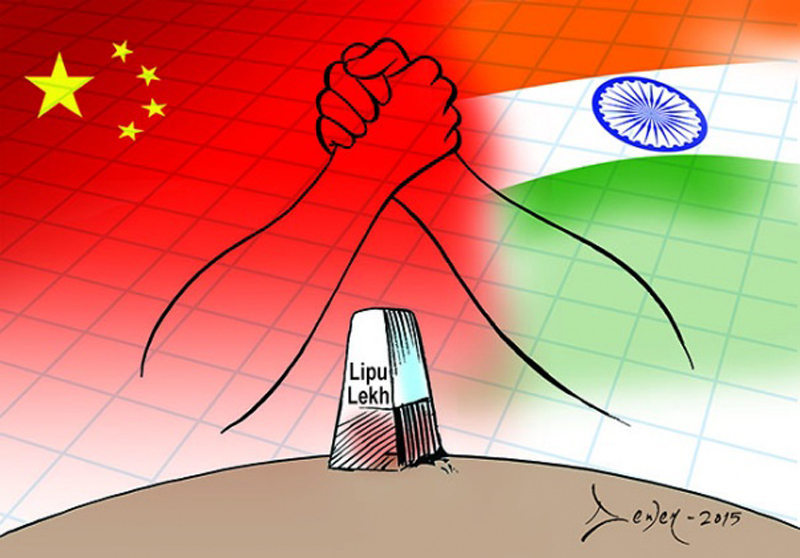

We should also not forget that at times India and China have in their bilateral dealings completely overlooked Nepal’s interests, for instance over Lipulekh, first in 2005 and then again in 2015. In both these instances, China seemed to accept that the tri-junction of Lipulekh between Nepal, India and China was actually a bi-junction between India and China. If there is a Doklam-like dispute over Lipulekh tomorrow, Nepal could find itself in the kind of helpless situation the Land of Thunder Dragon is in today, with the fate of its own boundaries out of Bhutan’s hands.

This is why we need an objective evaluation of China’s growing role in Nepal. With Nepal now an OBOR member, how do we ensure that Chinese money will be channeled into productive sectors, and that it won’t in time burden Nepal with a mountain of debt? Nepal, by agreeing to join OBOR, took the risk of alienating India, its indispensible (if at times arrogant) ally. In return, can China, as an expression of good faith, publicly accept that Lipulekh is indeed a tri-junction, and Nepal’s rights won’t be bargained away in its future dealings with India?

Beautiful distance

Nepal has had largely frictionless relations with China as the mighty Himalayas limited their interaction: it’s easy to be cordial to a distant friend. But as China’s rails and roads breach the mighty Tibetan plateau and penetrate Nepal, more friction is inevitable.

How do we minimize this friction and maintain a well-calibrated relation with India and China, taking great care not to lean heavily on either?

India has behaved abjectly in Nepal of late: by not recognizing a legitimate constitution, by imposing a crippling blockade, and by trying to micromanage events in Kathmandu. This happened because our political leaders were happy to do India’s bidding in return for political legitimacy in Nepal. It would be unfortunate if they now shift to Chinese camp and start unquestioningly following China’s prescribed course in Nepal.

There is a danger that we will learn the wrong lesson from Doklam. The lesson is not that India is by nature untrustworthy. The lesson is that both India and China have their own interests that don’t always coincide with those of small countries like Nepal and Bhutan, which in fact have often been treated as no more than dispensable pawns in the great geopolitical game.

biswasbaral@gmail.com

You May Like This

NOC slashes price of petrol by Rs 7 per liter, diesel and kerosene by Rs 5 per liter

KATHMANDU, May 15: Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC) has announced a significant reduction in the prices of petrol, diesel and kerosene. Read More...

Party's name will be Nepal Communist Party after merger: Leader Nepal

KAILALI, Feb 9: CPN-UML leader Madhav Kumar Nepal said that the name of the new party after merger between CPN-UMLand... Read More...

SCOPE Nepal provides foil blankets to Nepal Army

KATHMANDU, Jan: SCOPE Nepal, an NGO working in peace, security, environment and social justice, handed over 378 emergency foil blankets to... Read More...

Just In

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

- Mahakali Irrigation Project sees only 22 percent physical progress in 18 years

- Singapore now holds world's most powerful passport; Nepal stays at 98th

Leave A Comment