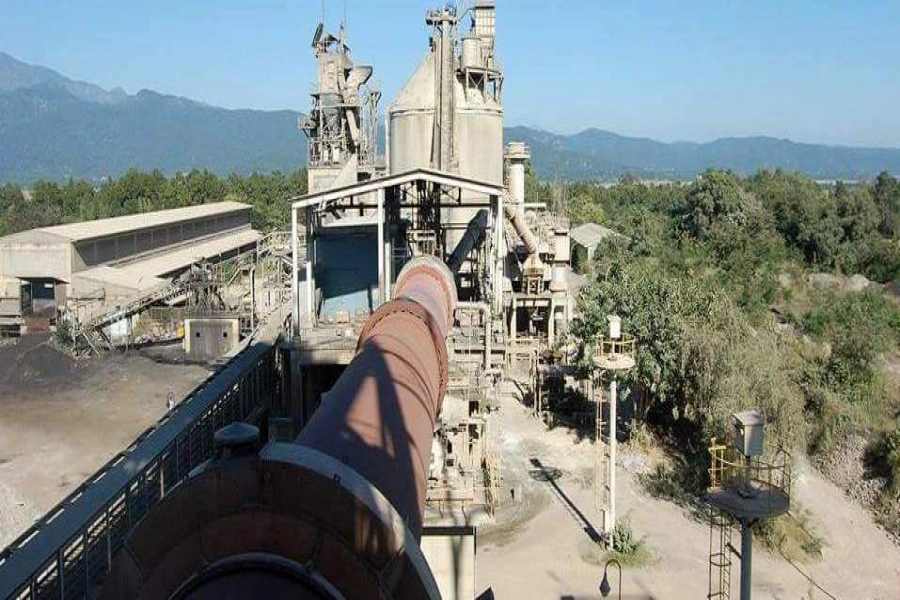

There are many reasons for Nepalis to be skeptical about high-sounding development plans. In the post-1990 dispensation, they have been promised so much, but so little has been delivered. Perhaps the most common electoral promise in the post-1990 politics was to light up every village in the country with round-the-clock electricity. Big hydroelectricity projects have been initiated, but very few of them have lived up to the high expectation. From Arun III to Trishuli 3A, there have been controversies galore about misappropriation of funds in these multi-billion rupee projects. The erstwhile Baburam Bhattarai government had taken the controversial decision to upgrade Trishuli 3A from 60 MW to 90 MW, against fierce opposition from hydro experts and other opposition parties who claimed that such an upgrade was both unnecessary and illegal. The Bhattarai government indeed found it hard to justify the upgrade which would deliver an extra 30 MW of electricity in the wet season, when the country doesn’t need any extra power. For instance, even as the year’s monsoon has only just started, Nepalis have been pleasantly surprised to find that the scheduled eight-hour load shedding has in reality shrunk to two hours as the run-of-the-river projects are starting to deliver peak power.

Here is the nub of matter. The Trishuli 3A upgrade is expected to result in an extra Rs 4 billion in profits for Gezhouba, the Chinese contractor. If the 90 MW project goes through, it is extremely likely that much of that profit will be funneled down to the actors that have played an instrumental role in pushing the upgrade up the political and bureaucratic ladder. In fact, barring the likely windfall for certain actors, the country will not in any way benefit from the upgrade. The extra four billion can be spent in other developmental activities, or even to start a new power project that can deliver power during dry months. It will be foolhardy to agree to the expenditure of such a colossal sum in the upgrade knowing full well that most of the amount will end up lining the pockets of unscrupulous bureaucrats and politicians. [break]

There have been cries from many quarters to crack down hard on the contractor for its failure to deliver the project on time. There have been calls for harsh fines. But such a strategy could be counterproductive. If the contractor is handed what it believes are unjust fines, it could abandon the whole project midstream, which would entail losses much bigger than the Rs 4 billion at play in the project upgrade. Rather, it would be in the best interest of both the contractor and the country to negotiate a new project completion date—without the upgrade. Such a middle way will allow the contractor to cut its losses while also giving it enough incentive to stay with the project. It will prevent billions of rupees from going down the drain and from further encouraging the corrupt. The Trishuli 3A will be a test case for the CIAA under its new head Lokman Singh Karki. How it handles the case will be closely watched: Can the country’s chief anti-graft body live up to popular expectations despite being in the news for all the wrong reasons of late?

'Trishuli Villa' operationalized with Rs 100 million investment