As Elinor Ostrom thus began her Prize Lecture at Stockholm University, she must have been aware of just how much surprise she had generated. In contrast, Oliver Williamson, with whom she shared the Prize, was not a surprise. A distinguished Professor of Economics (and Business, and Law) at Berkeley, holding 13 honorary degrees, with a 35-page CV, and an impeccable academic heritage, he had worked with several other Nobel Prize winners.[break]

“But Elinor Ostrom? Wasn’t she a Political Scientist from Indiana University?” A similarly decorated economist later described his field’s collective surprise. Many of the IP addresses logged by Google that day as having searched for her name no doubt pointed to some of the most influential Economics departments.

Indeed, those who knew her work were just as likely to be in poor countries as rich. And her friends say, she was as likely to be found studying canals in Sindhupalchok [in Nepal] with local colleagues and farmers as she was to be lecturing and writing. This set her apart from previous winners, and also made the honor so unexpected.

Her Prize lecture progressed. Lin, as her friends and colleagues called her, traced her work to the Nepali irrigation systems that she saw in 1988. Consequently, this was likely the first time that the word “Nepal” had ever been mentioned in a Nobel Prize lecture.* By the end of her speech, Nepal would appear eight times.

Ostrom was not a scholar of Nepal, but of ideas far more universal: user governance of shared economic resources. In the mid-1980s when the world considered the market or the state as the two options for organizing economic activity, she pointed to a third way. Users self-governing their activity, she claimed, could sometimes best manage shared resources. The real surprise, however, was the next claim: this sort of successful economic self-governance already existed, especially in remote areas, and it was nothing new. Her team’s sustained, systematic empirical work – a significant amount of it done in Nepal – found compelling evidence of the viability of these community-managed systems. Indeed, the lasting power of her studies came from the thousands of documented examples that her team used to make theoretical claims on.

Her 1990 book, “Governing the Commons,” laid out a new agenda for research in this direction. However, the path that she traced had high scientific standards. It called for visiting remote locations over long periods of time. It required scholars to step outside the logical cage of numerical relationships in the beginning. It asked that researchers also carefully observe what were occurring in the world beyond their own academic journals.

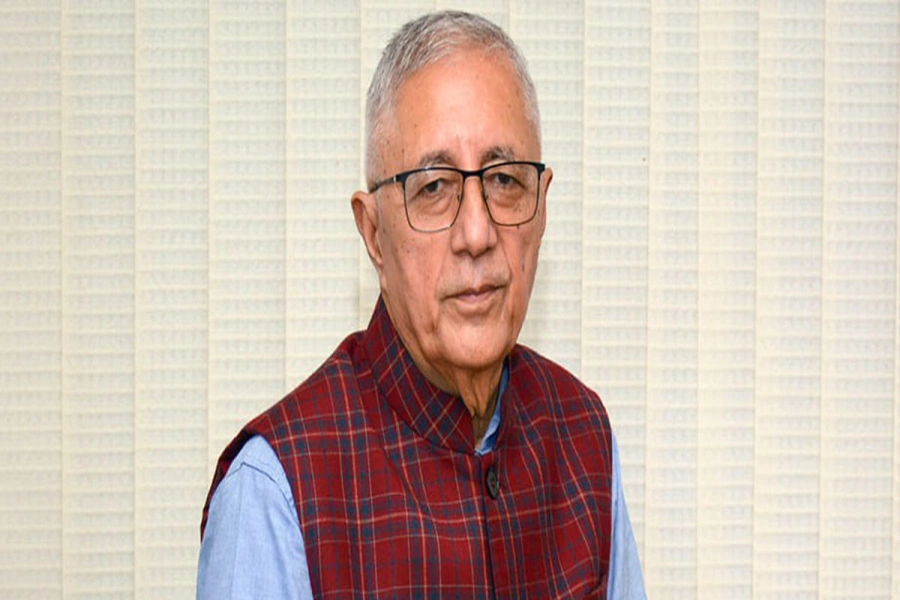

Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Economics. (Photo: REUTERS)

What is more, it compelled Western researchers to collaborate closely with local ones. It drew attention to the systematic importance of local conditions, and the implausibility of universal solutions. It also strove for a common vocabulary to communicate observations and findings. And finally, it did not promise anything new: despite all this work, scholars were likely to find that lots of very old systems worked well. For many scholars, this was too much to ask: her approach was clearly not very economical for quickly climbing academic ranks, especially when there were other paths to the top that had much simpler mathematical solutions.

It was not just her research style that was on the fringe. Elinor Ostrom herself was regarded as an outsider – a Political Scientist with little authority to question luminaries, sages and priests in Economics departments. Her work was used extensively in Political Science departments, or Departments of Planning, or Agricultural Sciences.

There were more unspoken biases: Real men did mathematical economics while Elinor Ostrom was a woman who relied on case studies. Students of Economics and Political Economy still find themselves hard pressed to name a single influential female theorist, even though Alfred Marshall’s wife co-wrote his first book.

Her insights were far ahead of their time, and about two decades ahead of the mainstream, male-dominated Economics profession. It seemed natural for economists then to believe that governing the market or harnessing it for purposes of justice were introducing “imperfections” in a natural order driven by self-interest. The fashionable theories suggested that much of economic organization should be left up to private firms and individuals, who in turn should focus single-pointedly on maximizing profits. The good and bad that resulted were considered as close to perfect as possible. Furthermore, in many areas of the economy, these private entities were said to self-regulate in a beautiful equilibrium. Economic perfection struggled against the forces of government intervention that sought to do anything more than provide “public goods.” It would not be an exaggeration to observe that the message of a natural order, and efficient allocation that resulted from, was carried to the far corners of the earth.

If these beliefs sound grossly and emphatically utopian now, it is important to remember that they were much less so then. When Ostrom was writing, economics was a popular faith that held that there were to be two types of goods (public and private and two forms of economic organization (market and state), and one type of human being (rational, self-interested, utility-maximizing). The main tools of enquiry were the manipulation of symbols, followed by scientific observation of reality. The world was admittedly complex, but the use of systematic observations to understand the complexity was confidently dismissed as soft and vague. Even as observation was given its place in proper method, it was not considered essential to it. Ostrom repeatedly pointed out this absurdity to her readers.

After the American economic problems of 2008, the euphoric belief in efficient perfection was no longer tenable. Confidence in these simplifications weakened slightly, and popular methods were debated. A few academics would continue to say publicly that financial markets could be perfect at all, with or without governance and regulation. The wake of a global crisis brought deeply unpleasant revelations. The wider world saw insider trading, suppression of whistleblowers, massively irresponsible investments, opaque and dangerous financial investment options being pushed by brokers, banks that were “too big to fail,” inaccurate credit ratings, and the fixing of important interest rates on a very large scale – sometimes in full view of the agencies set up to regulate them. To those on the outside, the collapse was clearly systemic: an economic system claiming perfection was actually hopelessly corrupt.

Naturally, questions arose about how such a self-destructive form of economic governance came to be justified in a democratic society that prized rigorous scientific inquiry and nurtured the world’s leading academic institutions. The damage caused by believing in untested ideas about economic organization implicated governments, financial markets, and most of all those who studied them. Quickly, the intricate web of theoretical models, concepts and methods that had led to and masked the crisis came under scrutiny. Even within the profession, prominent academics began to ask what went wrong.

One question came to the fore: How far had the field of Economics actually strayed from understanding human organizations to spreading a particular view of it? The gap between impartial scientific knowledge and superstition is large. And in the face of this scrutiny and scandal, the field had lost some of its scientific credibility. In the public eye, Economics was losing its monopoly on reliable economic knowledge, but at the same time, it retained its aura of being the most mathematically sophisticated of all the social sciences.

Nevertheless, those affected by the collapse ridiculed dominant models and demanded better economic governance. Here, the pendulum threatened to swing too far in the direction of outright dismissal: though the continuing crisis was a clear reminder of the limits of modeling, as economic theory and method clearly still had much to teach.

Ostrom’s work showed a possible way forward: she pointed to successful governance institutions that had weathered time and evolved to balance short-term private economic gains with the restrictions necessary for the long-term common good. These institutions, she reminded us, were neither the State nor the Market. What is more, they could be understood by extending the existing neoclassical framework, just slightly.

Even now her work does not apply directly to the larger economy, although it does apply to particular types of resources such as irrigation systems, fisheries, and forests. It also did not stray too far from neoclassical foundations, so the radicals were left unsatisfied. However, it did provide constructive and scientific examples of how governance can work well rather than faith-based arguments about how governance inevitably breaks down. This, in itself, was quite a contribution to academic debate.

It took close to fifty years for her ideas to reach a point of public acclaim. But it is still too early to know how far her ideas will take our search for better economic governance. Nevertheless, she has set a higher bar for research. For students, it can no longer be enough to translate equations from old mathematics articles into economic jargons and then claim superior knowledge of social organization. For policymakers, too – especially in weaker countries like Nepal – arguments advocating universal solutions based on idealized models have become slightly less compelling. At least in a small way, empirical observations and local collaboration, instead of large-scale data extraction, have gained some ground to informing new theories. As a consequence, those places that have been least studied may actually provide the most useful ideas.

Ostrom’s work heralds a time when Nepal, and intellectually marginal countries like it, may have much more to contribute to a global search for better economic governance. Provided, of course, that we have the confidence to admit, and find and study our own history of successes.

When Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Economics, passed away on June 12 of this year, it was reported that she was in the presence of friends, colleagues and family members. Perhaps it is not an exaggeration to suggest, either, that Nepal was also close to her heart at that time, just as it was earlier in her life. It is not unusual that it takes someone from the outside to recognize the potential of those on the inside. As we write a new Constitution, there is a lot to learn from other countries. However, Nepal would be wise to understand the potential of its existing institutions for managing economic resources. After all, new is not always better, and domestically produced is not always inferior.

*Nepal also appears in VS Naipaul’s own Nobel Address._Ed.

The author writes about economics, political economy and planning. He can be reached at pokharelatul@gmail.com

Interaction must for enhancing distance and classroom learning