The evils were: assets bubble, unmanageably high credit exposure of banks and financial institutions (BFIs) to the realty sector, and corporate governance problems, or financial crime by their top managements.[break]

These evils doomed Samjhana Finance. Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), the nation’s central bank or exchequer, decided to liquidate it in May.

United Development Bank is on the verge of facing a similar fate. These evils forced NRB to declare Gorkha Development Bank, another troubled institution and disabled Capital Merchant Banking and Finance from recovering loans and repaying its depositors.

Nepal Share Market and Finance succumbed to the unscrupulous deals of its top management, while People’s Finance surrendered to the NRB for the bailout. Vibor Bikas Bank, too, was forced to be the central bank’s lender of the last resort to be able to continue its operations.

Customers lined up in long queues to get their deposits back. At one point, the public in the market felt the country’s financial sector was in a mess.

They lost faith in institutions that served them for years – decades in some cases. Managers of many of these institutions faced confidence crises.

Despite that, by the time year 2011 nears its end, the sector casts a completely different look.

Once liquidity-strapped commercial banks now boast of liquidity surplus of over Rs 54 billion. Financial institutions, too, are operating at normal pace. Sharply eroded public confidence has gradually been restored.

The sector has been salvaged. Clearly, the credit of this turnaround goes to NRB, and Ministry of Finance (MoF).

But it will be a mistake if we take the quiet that pervades the market at present as a lasting peace.

That is because the goals of the policy intervention that NRB and the MoF made in January 2010 have not been achieved yet, i.e., the three evils have not yet been completely dealt with.

Though the banks are trying their best, they are still facing tough times in recovering loans issued in the realty sector.

That is because realty developers, who have absorbed as much as Rs 200 billion in loans from the banking and financial system, are still reluctant to oblige. And general consumers, on the other hand, perceive the prices are still unnaturally high and have decided not to buy land or housing until prices stabilize.

Instead of liquidating properties by lowering the prices, property developers and dealers are trying to take advantage of low confidence of the financial sector’s players.

They recently roped them in to convince the policymakers that if the prices crashed, the developers would be doomed and that would eventually harm the financial system as well.

Their argument is true to some extent. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) last year had revealed that if the prices of assets dropped by 30 percent, BFIs will suddenly find their NPA rising by 17 percent. If that happened, it will put the balance sheets of BFIs in red. But is there any other way out? No.

The property market must correct itself, for our economy can neither sustain nor bear the costs of its bubble.

Hence, the future course of Nepal’s financial sector’s health rests on two crucial reforms. First, reforms at the level of the central bank; and secondly, creating an institution called Asset Management Company (AMC).

Though we patted NRB’s back for the restoration of public and financial sector confidence, we, however, never appreciated the way it handled the situation.

Even while the public were panicking, the central bank leadership never came to the fore to address them publicly. NRB’s top brass never explained to them what it was doing to safeguard their money.

It took seemingly prudent steps but never realized the need of communicating its actions to the people. This approach must change.

Based on the jitters, IMF and NRB have strongly lobbied for entrusting new authority upon the central bank. However, the central bank officials have never openly debated why they need such authority.

As the country entered the crisis, everyone wished NRB to make public its immediate, medium and long-term plans in black and white over how it would manage the crisis then and in the future.

However, the central bank never did that. Intense debate on such matters would have only fortified NRB’s position.

However, NRB’s leadership is comfortable walking alone. In the process, it left itself to the circumstances to guide it than in taking steps to control circumstances.

This ad hocism better be discarded. Hence, we urge the NRB to chart out clear plans for handling tougher situations and discuss them with the stakeholders, so that they can prove effective at the time of need. Capacity development and strengthening of the central bank is a long pending issue.

It was much in vogue when Nepal took US$100 million for financial sector reform program in 2002. However, NRB’s capacity building remained the least implemented component.

Automation of the central bank, ensuring its access to data of BFIs, developing its inspection capacity and adding teeth to its supervisory functions and rules were pushed to the back burner. But the country simply cannot afford to ignore those issues now.

The government and the central bank, along with partners supporting the country’s financial sector, must immediately prioritize and work to strengthen the NRB.

With borrowers not repaying the loans, BFI top brass are already expressing fear over a huge chunk of their assets turning bad in 2012.

Hence, we suggest that the government and the central bank seriously focus at setting up an asset managing company, an institution that will take over the bad assets and liquidate them, enabling the banks to recoup the sunken money. This is pretty important if the central bank and MoF are to keep the BFIs’ health intact.

The authority concerned had converged at setting up AMC during the introduction of reforms in Nepal Bank Limited (NBL) and Rastriya Banijya Bank (RBB) as well, mainly to recover loans from chronic defaulters. However, it was unexecuted.

The authority cannot afford to ignore it now. Hence, we urge NRB and MoF to seriously start discussions on the structure and sources of capital for setting up AMC and activate this long pending institution.

Apart from that, we also feel the need of strong reforms at the BFIs level. BFIs are institutions that thrived under free market policy.

Sadly, however, the latest preference shown by bankers in maintaining high lending rates –despite being flushed with cash – even while the sentiments of the market are otherwise indicates our BFIs have little faith in market.

This has raised serious questions over their competence to exercise changes in interest rates and mobilizing the market. The bankers must answer this question sincerely and apply their professionalism to spurring demands and serving the market.

BFIs themselves must also take steps to ensure good corporate governance and also recover the investments stuck in the realty sector rather than volleying the issue to the central bank and MoF.

All stakeholders must act coherently and perform their respective duties with high morale and professionalism if the sector is to successfully overcome the challenges it is facing now. Otherwise, the sector in 2012 will find itself in rough tides yet again.

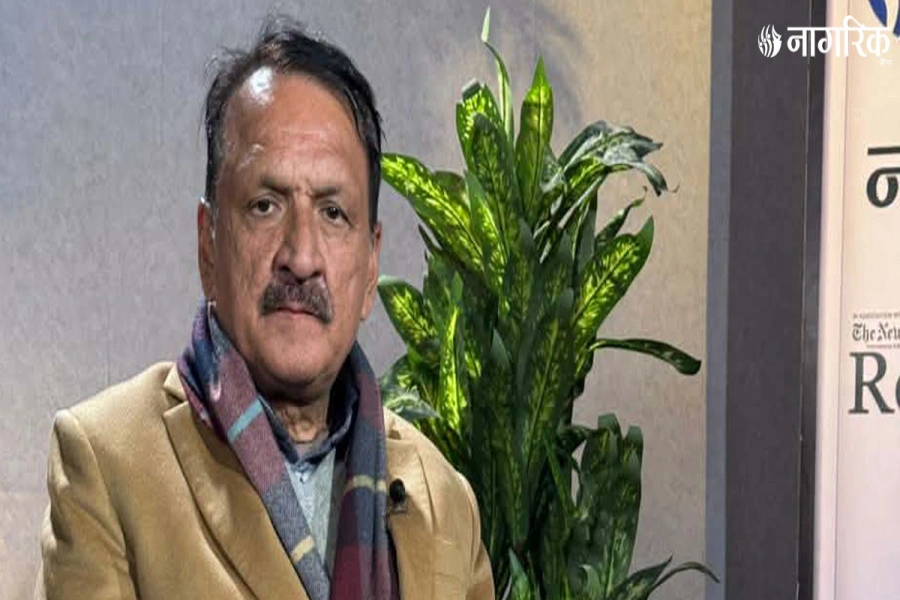

Sharma is the Business Editor of Republica

Anne Rice’s ‘Interview with the Vampire’ set for AMC in 2022