The lane that led to this transit was initially surrounded by barbed wires which now lay on the grounds, thanks to the villagers who night after night braved the wire to steal timber from the forest.[break]

However, when you walked a bit further from the transit, you would reach the ruins which served as a water reservoir for the British Recruitment Camps in the early 1980s. The ruins had nothing spectacular on its apparent appearance, which is why it was the best hideaway for me.

I had decided that I was bit too grownup for hide and seek and wanted to spend sometime in solitude, pondering over the questions that troubled me deeply.

“You should understand I’m a monk,” Pannawimalo said as we walked to his monastery. “My love is for one and all alike, you see,” he tried to smile gently as he explained why he could not be my “boyfriend.”

“I understand,” I said, not understanding anything at all. I stole a glance at him. He was draped in a maroon robe and orange blouse, walking loftily as sweat beads sunk into his dimpled cheeks and ran down to his neck, that beautiful, poised neck, which he would turn around to look at me again. “I understand.”

“You should go home now. I have a little discussion at the monastery tomorrow. Come if you can.”

Pannawimalo was a young Buddhist monk who visited our school and gave us a class on mindfulness or “sama sati.” I was assigned to assist him. Panna Vimal, which means the jewel of wisdom in Pali, personified everything serene and joyous to me. It was impossible not to fall in love.

“You’re too young,” he would tell me before I took a microbus home. He would caress my cheeks, and that caress had a potential to develop into a hug.

It was a full moon night, and the moon gradually washed away his warmth in her cool showers that rained throughout the night. I thought of the caress for a long time, until the moon-blanched night consumed me in a lovelorn slumber.

Two months later, I would be sixteen. I was not all that young, at least, not “too young.” Anyway, my mother would tell me I was “too old” to make excuses for not tidying our room I shared with my younger sister who always refused to believe in “moon-rains.”

The next day, I did not go to school. I went to the discourse. He talked on the impermanence of body, death and attachment.

His eyes glistened in joy as he partook in these talks on whose sheath I floated like driftwood, oblivious, fragile.

Sometimes I would hear him say, “This body is just a boat to take you ashore. Float to it, look around for truth.” I would retire from my drifting, think of my shore. What does a shore mean to driftwood, to the lovelorn driftwood, consumed in love for a river?

A group of layman disciples gathered around him and bowed to him and thanked him for the discourse. He looked at me, and let his eyes rest on me until some disciple distracted him for tea.

I felt his eyes; I felt the joy leap in my breasts. I left for home. I did not want to meet him, lest he would try to ruin it all with “look for a shore” thing again.

I came to the ruins. I had been in love before, but what was it about this caramel-skinned monk who saw my body as a boat when I am only driftwood? Who sees impermanence and death in the world where I see infinite awe and pleasure? Who sees attachment where I see romance? Who renders compassionate love, when I yearn for the passionate one?

Squirrels squeaked, threw a glace at me, and hurriedly left for their play.

Do they see me as a boat or driftwood? Do they see impermanence and death? Do they see romance? Did they see me at all?

The forest was awash with the cool aroma of eucalyptus trees. I let the soothing air heal my body and mind. The minty air seeped into me.

He spoke of desirelessness, he spoke of joy, he spoke in the language so alien, yet so true. He spoke to me like none other.

He hugged me before he left, and I tried not to let go. He smelled of geranium flower. He rubbed my back lovingly, soothed my grips and smiled at me.

He gave me the book “What The Buddha Taught” by Rahul Walpola. For many days, I could still smell him in the book.

The book changed my life completely. I started practicing Vipassana, much to my mother’s dismay, who found my silent sitting regressive for my academics.

I watched my breath come and go. I watched the death happen to me with every outgoing breath. I watched the impermanence of body and witnessed an extreme joy arise from the realization. I watched the realization fade away and I watched how desire consumed me again.

I was looking for the answer all around: The answer to that one question which would solve all my problems.

In a way, I believed, like Einstein’s Unified Theory, there was one equation, one solution, one answer that answered all my questions. Meditation, for the first time, brought the glimmer of that knowing.

Five years later, one fine morning, I got an email from him asking for my cell number. I replied immediately. He called me and asked how I was. I was good.

He asked me if I still remembered him. I did, at times. He asked me if I still loved him.

“You see, I’ve left the monkhood, I’m a free man now. And I think about you,” I heard him say. Ironically, following the path he showed, I took refuge in the teachings of Osho who did teach death and impermanence, yet encouraged us to partake in this transient beauty.

“I think we’ve drifted apart,” I told him. “I’m a sanyasin now. I’ve accepted the path of Osho. And I have a boyfriend.”

He kept quiet for a while. I felt his silence run all over me. I thought of the caress and the night when the moon rained throughout.

I thought of his caramel skin and his beautiful body that smelled of geranium flower. I thought of how I had desired him.

I thought of Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha who let go of austerity for desire only to unravel the exquisite pleasure in the world he renounced as an illusion.

“I’m so happy,” he said. “Nothing’s permanent here.” His words floated over me like the morning glory flower on a river, like billowing clouds float on azure sky.

Like love floats on the heart. Like impermanence floats on the river of life.We were but just driftwoods.

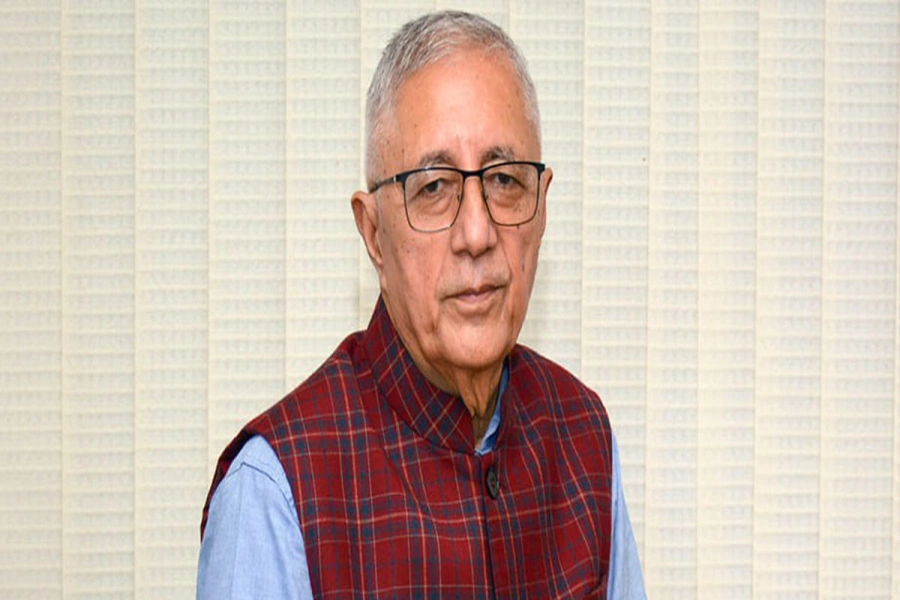

The writer is the Communication Officer at Nepal Investment Bank.

Lovers, comrades! Forbidden love in North Korea finds a way in...