OR

Priyasha Maharjan

The author is the Co-founder of Samartha Nepal’s program Janata Clinicnews@myrepublica.com

More from Author

In the name of containing the spread of COVID-19, the government should not ignore other health issues and let the citizens suffer bigger collateral damages.

Nepal was quick to follow the international trend of imposing restrictions to contain COVID-19 infection soon after reporting a few coronavirus cases. Starting with restrictions on international air-travel on March 22 to sealing land borders with India and announcing a nation-wide lockdown on March 24, Nepal’s strategy to prevent spread of the coronavirus and flattening the disease curve was well appreciated until collateral damages started becoming visible. The demerits of the decision easily exceeded its benefits to a point that many public health and other experts now state the lockdown was a mistake.

COVID-19 is undoubtedly a major crisis the globe is currently facing. However, lockdown was only a temporary measure: its purpose is not justified if nothing significant is done while everyone is confined in their homes. Just declaring the lockdown, deploying police on the streets to strictly implement it, and sealing the borders will not cure the coronavirus of an eternal existence. Protracted lockdown without ramping up preparation activities was a big mistake.

Here is how

First, Nepal’s progress in maternal and neonatal health was squandered. Decades of effort and work put in this sector is now in jeopardy as we witness neonatal deaths triple from 13 to 40 per 1000 live births. According to a survey by Human Rights Watch, still births and maternal mortality have also spiked owing to a significant decrease in attended births amid other social and economic costs. There is a looming fear of reversal for women’s health.

Second, the ongoing lockdown and parents’ fear of catching the coronavirus in a health facility has resulted in the disruption of vaccination programs. Moreover, the need for diversion of healthcare workers in COVID-19 management and issues with vaccines supply has only added to the problem. A recent study in John Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health suggests disruption of crucial services like immunization can result in as many as 6000 children dying worldwide every day, affecting 34.8 million children in South East Asia alone.

While WHO immunization and vaccines department head Kate O’Brien expressed her fear that diseases will come back resulting in deaths of unprecedented number of children, UNICEF executive director, Henrietta Fore, reported probable recurrence of measles, cholera and polio in Nepal. This situation can be prevented if the government acts promptly.

Third, though lockdown was a measure for protection, its consequences—fear, anxiety, and uncertainty among a large population—remains unaddressed. Being indoor bound with family members for longer periods has resulted in unhealthy family conflicts, breakdown, abuse, depression and domestic violence.

Misconception and stigmatization of the disease has only added to the mental health issues in the population. There are cases of self-harm resulting from lack of support from family members and society at large. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Nepal witnessed a 25 percent rise in suicide behavior with more than 2300 reported suicide cases.

Fourth, Kathmandu still does not have a dedicated COVID-19 treatment facility and the numbers of confirmed cases and human toll are only mounting up. The biggest challenge right now is asymptomatic transmission, particularly in young adults. The only answer here is testing larger masses such that people can start working and live a functioning life, with social distancing and other measures. There seems to be an absence of clear messaging about the disease status, testing facilities, preventive measures and hospitals to contact. There has not been adequate effort put into forming a team of risk communication experts, and placing stringent protocols at place.

Besides access to COVID-19 related facilities, the government has also put restrictions on general health check-ups and non-emergency surgeries. Adhering to this, many hospitals deny basic health care to patients, some even during emergencies. This has resulted in many health adversities. The government should at least now be prompt in arranging health logistics, technology and skilled manpower. It should not hesitate to recruit new health professionals and train them adequately.

Rethinking lockdown

Lockdown should never have been a one-size-fits-all strategy as it affects each income group differently. The poor population evidently bore a disproportionately higher burden of consequences. After a widespread food shortage and financial insecurity drove a mass exodus of migrant workers from the cities to their villages, the World Bank made a press release suggesting that Nepal ramp up its action to curb the health emergency and protect its most vulnerable population. The plan of action should have been different than that in developed nations because the impending economic toll and food security concerns are already visible in families just above and under the poverty line. With the use of limited savings, many more families are headed on the same course.

While early lockdown was a necessary measure to delay the pandemic, bolster healthcare facilities and prepare for its strategic management, its purpose was never fulfilled. The expansion of testing capacity; improvement of quarantine facilities; efficiency of surveillance measures and contact tracing abilities; and increment in the capacity of hospitals—nothing has been effectively worked upon these issues. The government’s response was poor with ineffective preparation, blatantly wasting months after the pandemic was declared by the WHO. The government imposed the first lockdown, only to lift it without adequate risk assessment and re-impose a second lockdown without proper strategy at place. Moreover, recovering from the harm this lockdown brought to our education, health care access and economy will be a challenge for an indefinite time.

As we advocate about embracing the new normal and living with the virus, we must also learn the notion of leaving no one behind—no one meaning the numerous issues and challenges that have hit us hard alongside the COVID-19 pandemic. Nepal should focus not only on COVID-19 management but also on recovering from the collateral loss incurred as a consequence of the lockdown. The socioeconomic inequalities arising from this crisis will only result in long-term health problems. The government advisory should, therefore, include a broad range of experts from economists and academicians to psychologists and mental health specialist to present a combined view of what would be the best in the context of Nepal. The answer will definitely not be a national lockdown.

The author is the Co-founder of Samartha Nepal’s program Janata Clinic

You May Like This

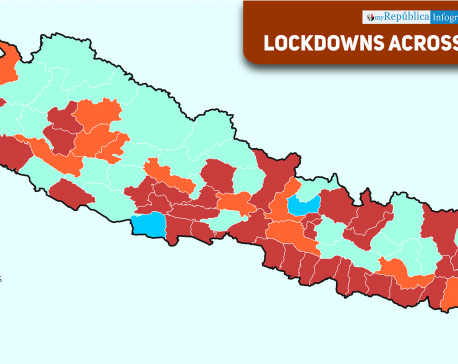

INFOGRAPHICS: 48 districts have partial or complete lockdown

KATHMANDU, Aug 24: Amid the rising number of novel coronavirus cases (COVID-19), most districts across the country have enforced lockdown. Read More...

12 crucial decisions taken by High Level Govt Committee to contain COVID-19

12 crucial decisions taken by High Level Govt Committee to contain COVID-19 ... Read More...

Stay home, stay home, and stay home

KATHMANDU, March 24: With a second case of COVID-19 recorded in Nepal this week, a bigger question is lurking: Is the... Read More...

Just In

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

- Mahakali Irrigation Project sees only 22 percent physical progress in 18 years

- Singapore now holds world's most powerful passport; Nepal stays at 98th

Leave A Comment