People from all walks of life walk the narrow mountain trail: Porters carrying loads weighing up to 60 kgs, toddlers perched on their parents' shoulders, young men and women with backpacks. As the mighty Koshi River roars below, mountain life comes alive in this picturesque but poverty-stricken place. And Rai, whose home and a small plot of land is higher up from here, has counted on this to make a small fortune.

Once it's completed, the 70,000-Rupee bamboo structure will house a grocery store. The centuries-old mountain trail once served as the main artery connecting the five hill districts to the vast southern plains, but it now sees only a trickle of travelers, thanks to an unprecedented drive to build roads in Nepal's rural hills.

Rai, however, is unfazed by such transformation. "Subsistence farmers like us could not earn much despite working hard. Our family grew larger while our farmland remained the same," Rai says.

After draining its three tributaries in Triveni, a few miles upstream from Rai's soon-to-be-completed bamboo hut, Nepal's largest river becomes Sapta Koshi. Passing through diverse landscapes, climates and lifestyles, the Sapta Koshi sustains tens of thousands of mountain communities. Drawing on the life supported by the river, these indigenous people settled here and for generations have adapted to the often capricious ways of the Koshi.

To the villagers along the Koshi River, it offers many bounties: People wash clothes and bathe in the water that looks green from the riverbanks. Goods are transported on bamboo rafts; people cross the river drifting on plastic tubes, fishing nets are cast.

A few miles downstream, thousands of pilgrims visit the Barah Kshetra, one of the holiest pilgrimage places for Hindus. Up in Triveni in late February, hundreds of villagers congregate for Saptaha Puran, a week-long religious gathering.

But everything that the villagers hold dear will be threatened if Indian and Nepali officials and politicians are allowed to prevail with their plan to tame the river.

An ambitious multi-billion dollar, 269-metre, multi-purpose concrete and cement dam with a capacity to generate 3,300 Megawatt (MW) of hydroelectricity has been proposed at a place called Sunakhambi, two kilometers upstream from of Barah Kshetra.

If the Sapta Koshi High Dam goes ahead, it will displace an estimated 75,000 people living in over 80 riverside villages of the seven districts of Dhankuta, Sankhuwasabha, Bhojpur, Khotang, Okhaldhunga, Udaypur, and Tehrathum.

While government officials never tire of talking about its benefits to Nepal—half a million hectares of farmland in Nepal and more than double that in India to be irrigated by a network of canals, and navigation through the river—the Sapta Koshi High Dam aims to control the annual monsoon floods downstream in the Indian state of Bihar.

Opinions were divided on whether the solution to flooding lay on the embankments or the high dam in the Himalayan foothills. The decades-old idea of Sapta Koshi High Dam received a boost after the official visit of Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala who agreed to form a Nepal-India Joint Team of Experts to investigate the modalities and assess the benefits of the project. But the work began in earnest only in August 2004 when the Joint Project Office was set up in Biratnagar. It was tasked with preparing a Detailed Project Report (DPR) to investigate the environmental and socio-economic impacts of the project.

A decade-long grassroots protest movement has stymied any progress on the work on the DPR. On January 17, as in the past, hundreds of villagers gathered under a shade at the Baraha Kshetra Temple complex and protested against the work on the DPR, demanding that it be halted immediately. A week later, the drilling the Joint Project Office had been conducting at the dam site was withdrawn.

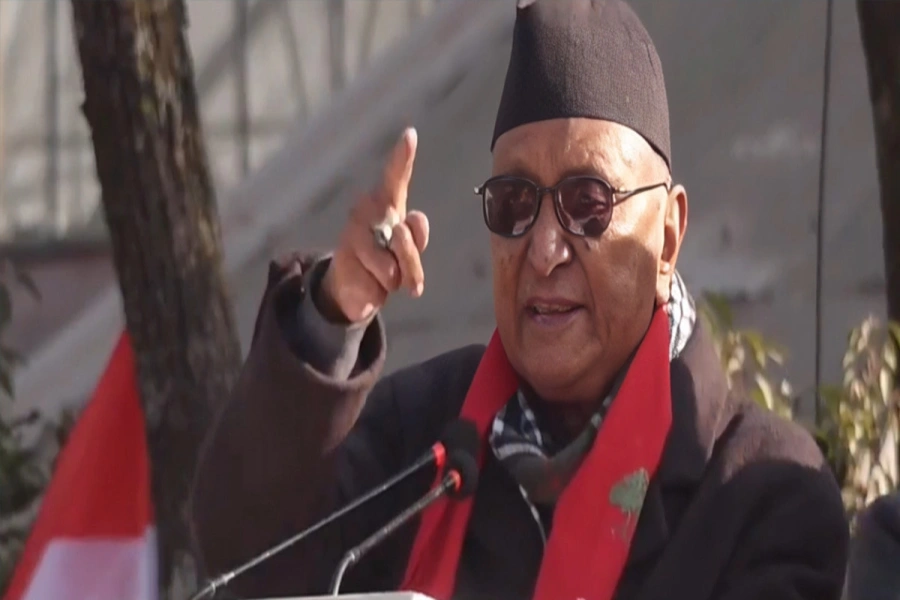

The villagers, mostly farmers, have coalesced around Ganesh Bahadur Rai, a chain-smoking septuagenarian. They have organized themselves under the banner of Saptakoshi Jana Adhikar Manch, which has its footprints in nine districts and has around 5,000 members. The signs of protests are everywhere: "ILO 169" is painted on rocks along the trail. Their message is loud and clear: the locals want their rights protected under the International Labor Organization declarations.

Rai speaks passionately of the battle he's been waging in the twilight of his life.

"We regard our rivers as our country's lifelines. This is a national treasure," he says, adding that the dam dissent doesn't mean they are against development. "We don't oppose development, but development at what cost and for whom?" he says.

In the 1950s, New Delhi signed the Koshi Agreement and the Gandak Agreement with Kathmandu. Critics of the treaties argue it was unequal and favorable to India. Indeed, the treaties, signed when Nepal had just emerged from a century of oligarchic Rana rule, have provoked political passions, setting off decades-long anti-India campaigns that have damaged the bilateral relations. Such legacy doesn't inspire optimism to Rai, a retired local cadre of the ruling Unified Marxist-Leninist Party.

"We're determined not to let our leaders commit mistakes again. We want to save the Koshi from such follies," he says.

As Rai holds forth in the hamlet of Simle on the banks of the Arun River, Bam Prakash Rai, 48, who lives with his family in Chhintang Village of Dhankuta District, echoes the elder villager's concerns.

"We won't obstruct the work if our own government builds the dam. But India is doing it and we can't trust our neighbor," Bam says and points at the failure on India's part to pay compensations for the flood victims of 1984 when the Koshi had breached its embankments. He also fears that with a weak Nepali state, their future is at stake.

The villagers are equally angry at their politicians.

"We pleaded our case with every leader of every political party representing these districts. They assured us that they would raise the issue in the Parliament, but then they forgot everything," Bam Prakash Rai adds. "We'll lose our homes, forests, gardens, temples and our way of life."

Most villagers agree the government should resettle them before it starts work on the project.

Dinesh Kumar Ghimire, Director General of the Department of Electricity Development in Kathmandu, says the government is seeking an all-party consensus to resolve the issue.

"We're trying to build trust and persuade the locals through political parties," he says and adds that the very idea of DPR was to assess the local people's needs and help them resettle. [But] "If they obstruct our work on the DPR, how will we know the impacts of the project on local people's lives, livelihood and the entire Basin?"

The people at the hamlet of Simle, however, are far from convinced. With India pushing for the project and the DPR going ahead, they say their bargaining power will significantly weaken. For the thousands of people living precariously by the Koshi River, therefore, it's now or never.

deepak.adhikari@gmail.com

Home Ministry warns of releasing excess water from Kulekhani Da...