A CONCISE HISTORY

As capitalism was taking hold in Europe, a debate was emerging on the future of agrarian societies. The initial expectation had been that capitalism would consume the peasantry, turning agrarians into proletariats that feed the capitalist machinery. However, over time, despite the expected economies of scale for large companies, peasants survived through what Kautsky called their “drudgery”: they worked harder for longer hours and consumed less.

The agrarian question encompasses a number of very interesting dimensions concerning surplus, accumulation, and political mobilization of the agrarian class. However, there is no singular resolution to the problem of transition. In England, capitalist tenant farmers invested heavily, with help from the class of landed property, to lead to the industrial revolution. In Japan, an intense class conflict between an exploited peasantry and an extractive state was central to industrialization. The Taiwanese/South Korean path also followed a similar trajectory, with the state accumulating from the peasants to transform to an industrial, capitalist country.

THE RUSSIAN PEASANTRY

Marx’s analysis of the Russian peasantry provides a gem of an example of the contemporary relevance of the agrarian question. At the time, Russia was a formally independent but internationally weak state, with a dominant small-scale peasant population. The interventionist state was rapidly industrializing the peasantry, often against its will. Their fate was situated within the context of global economic processes, as the commune was linked to a world market in which capitalist production is predominant.

If Nepal is to “develop” it must address the complexities shaping agriculture and forces affecting its transition.

The parallel of this Russian analysis to the contemporary scenario is striking. Developing countries are rapidly industrializing (or being pressured to do so) in the neoliberal global economic order that can be extremely exploitative. As corporations like Monsanto increase their dominance globally, including expressing interest in Nepal, their competitive advantage helps them squeeze the peasantry into compliance.

The peasants might be down but they are not out though: they continue to persist with their drudgery rather than simply roll over and become co-opted by the machinery.

THE NEPALI CONTEXT

There are a lot of obvious similarities between the current state of Nepali peasantry and the agrarian discourse at large. Nepal remains a predominantly agrarian society transitioning into the global economy under the auspices of a weak state.

However, there is a striking difference in that Nepal has embraced modernity without experiencing industrialization.

The industrial hubs of Nepal, most notably in the East, provided political fertility to launch Nepal’s early democratic claims, but have failed to prosper productively. Ironically, the political problematic has paralyzed industry, with competing political labor unions and party-based local and national strikes severely undermining the scope of investment and production in the sector.

The weak state has failed to implement serious land reforms and taxation mechanisms to successfully accumulate from the peasantry. Concurrently, it has also failed to provide effective subsidies or other breaks to help peasants earn a meaningful living. The transitional phase is thus in limbo, with both the peasantry and the industrial sectors in static, disregarded existence.

NEW FORCES

Based on my recent field visits, it is clear that the agrarian question in the Nepali context is not about the wheels of industrial capitalism but of the penetration of capital through migratory globalization. The universalization of the “American dream”, where people believe in the potential for upward mobility, has led to extremely high expectations. However, the lack of opportunities at home has led to deep frustrations, with up to 1,400 Nepalis leaving the country in search of employment each day. The resulting impact on peasant households is powerful.

First, there are fewer people to work the fields, and women are increasingly burdened with farm work. The tradition of labor sharing (locally known as mela paat) in the outskirts of Kathmandu, for instance, is sustained entirely by women while men look for work in the cities, if not abroad.

Second, a lot of new money is entering villages, mostly through the much-touted remittance returns from abroad. This inflow is not only affecting spending and consumption patterns but also supporting investments in the agricultural sector, with many families now more able to use manure, raise cattle, and pursue other livelihood opportunities.

Third, population pressures on the capital have meant that the price of land skyrocketed a few years ago, and has stabilized there. Villagers want to rush to the cities in search of “better lives” whereas the rich middle class look to escape the hustle in search of “beautiful suburbia” in the outskirts. Even a small piece of barren, unproductive land can fetch good money that peasant households are able to invest on better houses, higher education and small enterprises.

The increasing investment on human development has meant that the youth force is turning away from agriculture as a way of life. It is not because they cannot compete with the capitalistic machinery but because they seem uninterested to compete in the first place. Small-scale farming is increasingly a matter of last resort, and many of the “educated” would rather remain unemployed than toil in the farms.

Family size and dynamics also contribute to eroding interest in farming. When land is inherited by a generation from a previous one, subsequent land holding size decreases. The commoditization of land has already decreased the amount available for inheritance, so as that size decreases, peasant families find it more attractive to sell their land, mostly to outsiders, than to continue to farm for sustenance.

WHAT NEXT?

The question remains as to how, if at all, Nepal will transition from its current status as an agrarian society. Contesting forces have made it possible for greater investment alongside less interest in the agrarian way of life. It is not that the Nepali peasants are disappearing altogether: their capacity for drudgery is obvious as they wake up before dawn to toil in the fields and walk hours to sell their produce.

They work harder to make ends meet, as giving up is just not an option. However, as new avenues of employment and greater hopes of “Development” seep into the public conscience, people are increasingly turning away from the agrarian way of life. The sustainability of immigration and inflow of remittance will undoubtedly affect the direction of the resolution of the agrarian question.

Given Nepal’s political economy today, it looks unlikely that industrialization will pose a serious threat to the survival of the agrarian class, even as the agrarians themselves look for alternatives to escape their way of life. The trajectory of Nepal’s transition in this mobile, more connected age could provide answers and pose further questions to the different layers of the agrarian question.

If Nepal is to make progress in its quest to “develop”, it must address the complexities that shape the current state of agriculture and the forces that affect its transition. This piece provokes only the bare bones of the issue, but a deeper analysis is urgently required to address these issues.

shrochis@gmail.com

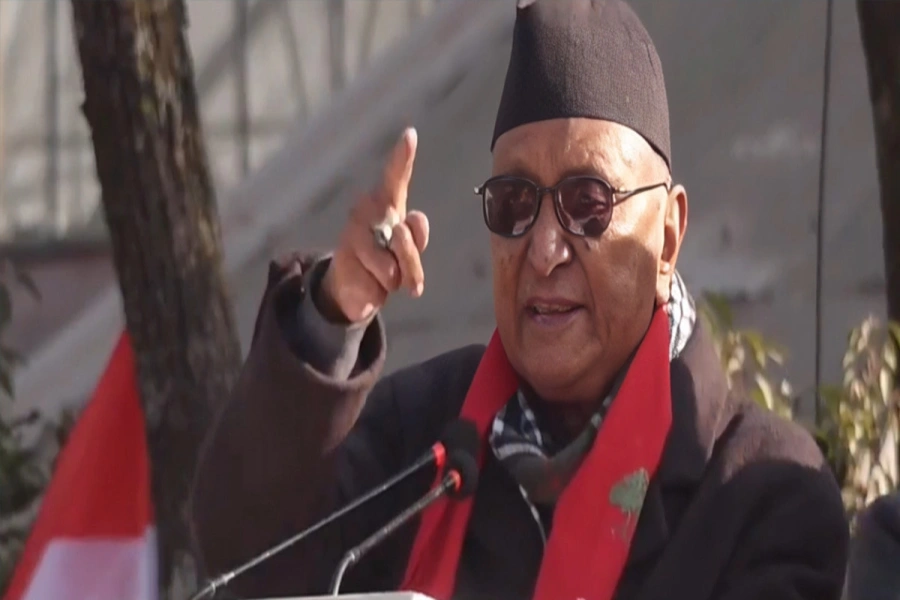

Province-2 will be made an agrarian province