OR

High taxation policy pursued by Nepal has worked as a powerful drag on the economy by hurting private sector incentive and discouraging foreign investment

Taxes that Nepali citizens pay to the government look onerous and usurious. Most tax gets assessed randomly with the sole objective of transferring money to government treasury while little attention is paid to its impact on the larger economy and on public welfare generally. In large part, government’s approach to making use of public money isn’t helping to improve public safety and security or provide them with basic services that provide the original justification for government levying and collecting taxes.

Many of us may not appreciate this but tax collection has been one area where the government of Nepal has carried out its duties diligently, even ruthlessly. Looking at recent history, government collected Rs 200 billion in tax revenue during fiscal 2010/2011, from tax and nontax sources. By fiscal 2018/2019, total revenue increased to Rs. 946 billion which is a fivefold increase and a much higher rate of growth than in national income.

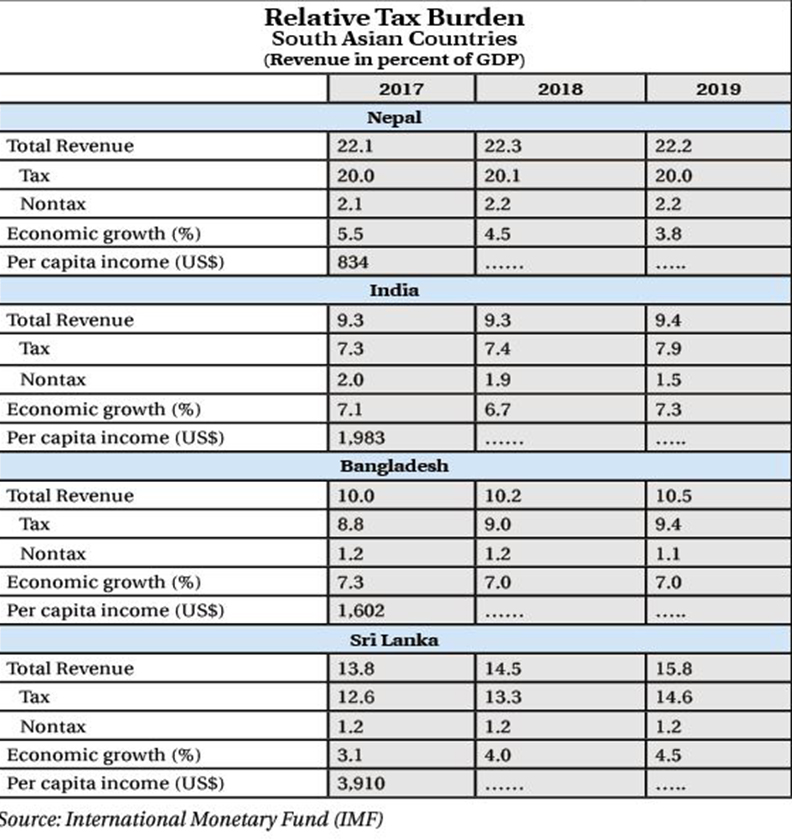

A better perspective on Nepal’s focus on its tax performance is given by revenue collection in terms of GDP—or total output of goods and services in the economy. The revenue-GDP ratio—a measure of how much of national income is collected in taxes—increased from 14.5 percent in 2010/2011 to 22.3 percent in 2018/19, or by over 50 percent. Comparing regionally, revenue collection in 2018 amounted to 9.3 percent of GDP in India and 10.1 percent in Bangladesh or less than half level in Nepal. Also noteworthy is the fact that revenue-GDP ratio normally stays unchanged over long periods of time and this also has been the case in India and Bangladesh, in contrast to its escalation in Nepal.

Taxation with little service

It is understood that the intent of revenue collection is to pay for public services provided by the government, collectively known as Current Budget items. This fiscal year’s budget allocation for current spending is Rs. 845 billion, equal to 90 percent of total revenue and 30 percent of GDP.

At this level, current spending in Nepal is higher than in Bangladesh and also higher than in India. As a share of total revenue, Bangladesh spends 80 percent on current spending items, which is 10 percentage points lower than Nepal. As a percentage of GDP, the difference in current budget spending is more striking—15 percent versus 30 percent. The latter is for Nepal. A further point to note is that Bangladesh collects less than 10 percent of GDP in revenue which, again, is less than half of Nepal’s. Comparison with India gives quite the similar figures.

Comparison with other countries will likely be not much different than for Bangladesh and India. These data present an extreme case of profligate spending by Nepal Government which is much out of line with many other countries, in terms of how much it should collect in taxes; how much of tax collection it should save; and what level of services it should provide to match the revenue it collects.

Admittedly, these numbers pose profound types of policy questions. If Bangladesh can save 20 percent of its tax revenue after paying for current spending while taking in just half the amount (in terms of GDP) in tax revenue why should Nepal spend 90 percent of its twice larger tax receipts on current spending items? Further, there is little evidence that the range and quality of public services in Nepal is twice as good as in Bangladesh. About a similar comparison exists with India and perhaps with most other comparable countries in the region.

The tragedy for Nepal—and tragedy it is—is that it has imposed super-sized government infrastructure over the population who is forced to bear super-sized tax burden to sustain it. While much of the population works on farms and in factories taking in subsistence level wages, government officials get paid comfortable size salaries with job guarantees, health insurance, pension benefits and extra earnings from bribes in certain situations. As an indication of how lucrative working for government can be, government positions get sold in under-the-table deals for the money multiple times higher than annual salaries.

A further point is that, even discounting for higher education and skill levels of government workforce, average remuneration in government sector may be three or four times higher than earnings in the private sector. At the same time, a case can be made that social value added by government workers, on average, is lower than value-added by private sector workers, especially in situations like in Nepal that have overstaffed government offices and little or no supervision over work performed.

Low growth

Although there is no direct relation of taxes to economic growth, the two are related in a number of ways that are not so obvious. Government usually saves part of its revenue to provide for capital funding. For a developing country like Nepal, savings from budget has been a sizeable part of investment and it makes a powerful case for high government tax collection.

Beside the investment argument, size of tax collection determines, in part, government’s absorption capacity that helps attract foreign capital, most importantly foreign grants and loans. Indeed, high tax collection is normally pushed by donor country agencies and international institutions as condition for foreign aid which, for Nepal government, has provided powerful justification for maintaining a high tax regime.

Despite these advantages of tax collection for economic growth, this relationship for Nepal has been quite the opposite. With almost twice the level of tax collection relative to GDP, the country’s growth performance has been inferior by about a third relative to Bangladesh and also India. This provides a strong evidence that high taxation policy pursued by government of Nepal—some of it applied indiscriminately—has worked as a powerful drag on the economy by hurting private sector incentive and, in particular, discouraging foreign investment which, traditionally, has been lower than in comparable countries.

Government for government

Government exists for the people but, in some cases, people exist for the government. While the first part of this statement is widely shared and agreed upon, it is rare that the second part of the statement gets recognized as a possible case. However, we can argue that in situations like in Nepal, the country exists for the ruler and people are used for a cover, to provide recognition and legitimacy.

In Nepal’s case, despite its democratic façade, there is little evidence that ruling autocracy cares for the people except for talking cheap—selling the dream of double-digit economic growth and turning Nepal into Korea or Singapore. Government has failed miserably in providing essential public services, especially if one looks at the mammoth-size tax it collects from citizens, most of whom live in dire poverty without social protection. Also, there is no evidence that future improvements are possible in an environment of lackluster growth. Thus there is nothing to expect for growth momentum to accelerate and government policy to change in a way that enables people to share the fruits of growth.

‘Government for government’ characterization reflects in heavy taxation of population with little improvement in public service delivery and growth performance. This means the government is not using the tax money for public welfare purposes as observed, to a large extent, in Bangladesh and India, where tax collection is much lower and provision of public services more improved and numerous.

This degree of mismatch provides a compelling evidence of the misuse of public money by the government in Nepal that isn’t seen even in dictatorial regimes which aren’t committed to public accountability. And looking ahead, there is little evidence that public policy will shift toward putting tax money to better use, tax burden will be reduced or be brought in line with that existing in neighboring countries.

The author teaches Economics at NOVA College, Virginia

sshah1983@hotmail.com

You May Like This

Nepal’s solar aspirations

Planned and sustainable development of solar energy as part of a larger green energy development plan can truly help Nepal... Read More...

How I suffered violence

Women are still being character-assassinated. How many more suffering women does it take to change Nepali society’s mindset toward domestic... Read More...

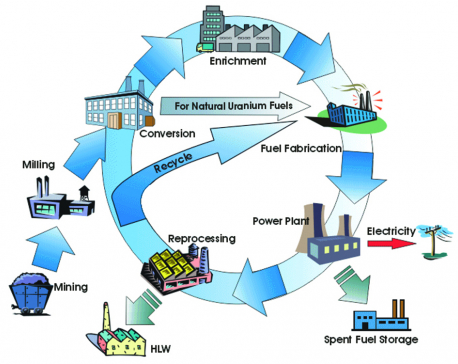

Why this Nuclear Bill?

Nepal appears to be poised for a heedless jump into the thick of nuclear research reactors and nuclear fuel cycle... Read More...

Just In

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

- Mahakali Irrigation Project sees only 22 percent physical progress in 18 years

- Singapore now holds world's most powerful passport; Nepal stays at 98th

Leave A Comment