Trumpism and Oli-garchy may keep on raising their heads time and again, but it is the people who make history by their collective action, and who continue to carve new forms of democracy.

The rhetoric of “End of Democracy” is apparently transforming itself into a gloomy reality in many countries of the world. It rhymes with “End of History”, the catchphrase of the 90s popularized by Francis Fukuyama, but carries a meaning opposite to what the latter implied—the demise of Western liberal democracy.

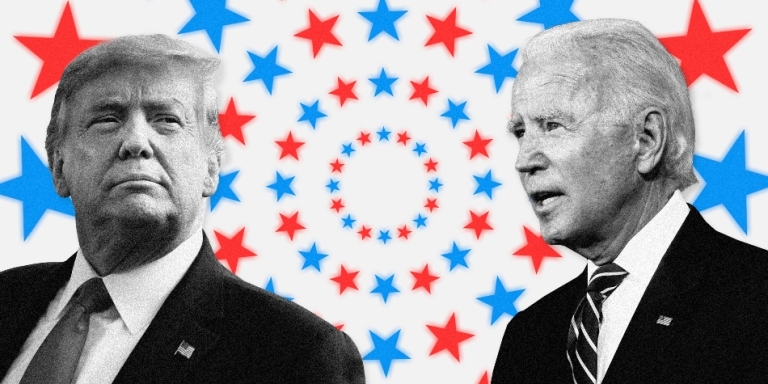

Jack Daniels, the Broadway actor of To kill a Mockingbird fame declared a few months ago: “It is the end of democracy if Donald Trump gets reelected.” It seems, however, the sorrows of democracy may not end with Trump’s defeat in the election, nor with formal acceptance of election results by the Congress of United States of America. It may linger on and its variants may appear in other places of the globe. Nepal’s recent political events before and after the unconstitutional dissolution of the Parliament by the elected prime minister appear to be just another end of that continuum.

Alarming signs in the US

Trump has not been reelected but so far he has refused to acknowledge the decision of Federal Election Commission declaring Joe Biden victorious with a lead of 306 to 232 Electoral College votes. He had persistently claimed voter fraud and demanded recounting of votes in selected swing states.

The statement of Trump’s former security advisor Michel Flynn two weeks ago for imposing martial law and military mobilization to force new elections on these swing states had caused a tremor of palpable concern about the proceedings of the joint session of upper and lower house of Congress to be held on January 6 (today).

No one should dream of going against democracy: PM Deuba

One indication of such an alarm is the ban to carry guns by pro-Trump protestors. Trump encouraged protests in Washington on Monday while a group of republican congressmen and senators under Ted Cruiz planned to challenge the election results calling for investigation of election fraud in the House. And to top it all, in his public speech on Tuesday he openly called Vice President Mike Pence to reject the results of Electoral College when they come before the Congress. Amidst these ominous developments, Trump’s leaked phone call pressuring Georgia’s secretary to ‘find’ 11780 votes for his victory has earned him a warning of second impeachment on attempted vote rigging and contempt of democracy. The state of Georgia had become the last bone of contention, because the election results would have determined whether Democrats gain majority in the Senate or not, crucial for implementation of their policies. If they lose, their policies may be blocked in the US senate for another two years.

Such sorry state of the US election and all the strings attached to it in supposedly world’s greatest democratic country raises painful questions about viability of a representative democracy. The phrase “end of democracy”, however, is not exclusively associated with Trump nor did it emerge from the US. Apart from Marxian critics of ‘ bourgeois democracy’ this catchphrase of democracy’s end was, in all probability, first noted after the failure of Arab Spring in Egypt of 2011 when the popularly elected government of Mohammad Morsi of Muslim Brotherhood could not translate political democracy into economic development. As a consequence, Morsi who had come after overthrowing Hosni Mubarak by a popular movement, was toppled by Army rule, and died in the prison. Between 2011 and 2015, sinking along with the crisis of neoliberal economy, democratic governance of many countries lurched into a backward swing, raising bitter questions about the viability of Western liberal democracy.

The phrase found a global spotlight in the 2015 Davos World Economic Forum Conference when a session was organized on this theme among the learned scholars and politicians from different countries, including Egypt. The moderator of the program recounted accusations hurled at the weakness of democracy: It produces corrupt politicians who are incompetent, they are failing to protect minorities even in economically advanced countries, its governance are too short to address effectively issues like climate change, it has become money politics, the rich and mighty can buy the outcome they want etc.

Some of these accusations ring true for Nepal, the intensity being incomparably grievous, given Nepal’s late transition from feudal monarchy to democratic republic and all the birth marks of past society it carries with it as it ushers into a new era. The election itself has degraded into a strong compulsion for corruption. And what if the rich and mighty use their power ‘to buy the outcome’ of election, and if they do not get what they had desired then refuse to accept it?

End or continuity?

This change of mood from elation to apprehension about Western democracy is dramatic, comparable to the aura of Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’. He had explained triumphantly: “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Fond hopes of Western liberal democracy as ‘endpoint of ideological evolution’ and the ‘final’ form of human government did not last long. Fukuyama soon found himself in defensive, forced to acknowledge troubles within liberal democracies and to provide explanations about them. The phrase ended up as deflated ‘rhetoric’ in the first decade of the 21st century as the global neoliberal economy, the frontliner in raising the banner of Western liberal democracy, found itself in insurmountable crisis. Even before that, in fact a year after the publication of Fukuyama’s book, Andre Gunter Frank had rebutted such simplistic concept of history in his article “No End to History.” He wrote: “The course of history, which is largely driven by economic forces, shows that neither history itself nor his or our ideas of history- even of democracy are at end.”

Marxist scholar Frank’s thoughts seem prophetic in contemporary discourse because he appears to anticipate another trend of thought that could spring from another extreme of the same mindset—‘universalization’ of Western liberal democracy at one end and its ‘demise’ in the other. History does not end, nor does it move in perpetual cycles. It moves in spirals with an upward axis. A seeming end of something may be a beginning of something else. The ‘end’ of Western representative democracy, or the ‘rule of majority,’ may appear to be at the end but alternative practices to rejuvenate it are already in motion in different parts of the world, Nepal included.

Nepal’s endorsement of inclusive and proportionate democracy in its 2015 Constitution was one such alternative form. There are other forms such as participatory democracy, direct democracy and deliberative democracy—all interrelated with each other while the adjectives before each variant of democracy underline their relative emphasis. They contend against emphasis on voting as the sole source of legitimacy of representation and posit consultation, deliberation, consensus and merit as more important source of such legitimacy from voter participants combining different form of representations with them.

The simplistic notion of democracy as the ‘rule of majority’ has long been contended both in ancient and modern times. Most of the founding fathers of America saw this form of democracy as another form of tyranny. It may suffice to quote two of them. Thomas Paine who penned Common Sense and Rights of Man and influenced the writing of United States Declaration of Independence says: “A democracy is the most vile form of government there is”. And John Adams, the second president of America wrote: “Remember democracy never lasts long, it soon wastes itself, exhausts and murders itself. There was never a democracy yet that did not commit suicide.”

Such deep distrust of democracy appears to have its root in the thoughts of great philosophers of Greece. Philosophy was against democracy at that time. Athenians were ruled by democratic order while Socrates and Plato both were opposed to it because they doubted in the majority’s decision to find the right solution. The grim irony of democracy, as it turned out, was that the death sentence to Socrates was decided by a marginal majority vote of 52 to 48 percent among 500 Athenians selected for the judgment.

David Runciman, the Cambridge Professor of Politics and History distills three main objections of Plato to democracy. He argues that if allowed to rule by democracy, it would be a rule by the poor, the illiterate and the young. Even though the voting rights were restricted, it would be so because the population of ancient Greece was predominantly young, poor and illiterate. The Athenian democracy failed at the end, and that it failed because nobody wants to be ruled by the poor, illiterate and young became the winning argument held for about 2000 years or so. Only in the 18th century Europe with the advent of age of enlightenment and renaissance, such deeply held rational was opposed and the argument in favor of universal suffrage began to evolve.

But the rebuttal of established argument against democracy was achieved by a concept of representative democracy as Runciman explains, by ‘deliberately designed’ arguments that even though the society may be largely poor, uneducated and young, the people who could fight election would be predominantly rich, educated and old, because one could not fight election if that person is poor and uneducated and young. It is because the candidate needs money and education and experience. This argument turned the tide in favor of representative democracy, but Ruciman submits, it was not just an argument it was the Truth. The history of two centuries shows that this is exactly happening about who gets elected.

Resolving contradiction

This anomaly between the characteristics of electorate and the elected creates the contradiction in liberal democracy. Marxists would interpret it as class contradiction. This contradiction cannot be resolved unless electorate mass is truly represented in the elected representatives, so that they have a say in shaping the policy of their communities and nations. Ancient Greek philosophers thought societal composition as absolute founded on great divide of masters and slave, elites and the commoners. In modern society the composition of electorate is radically changing, becoming more conscious of their civil rights and eager to come out of poverty and ignorance and inexperience. The individuals—whether poor, uneducated or marginalized—demand to be seen and treated in equal footing.

A form of democracy ‘that produces corrupt politicians who are incompetent, who fail to protect minorities and marginalized population, caste or linguistic groups, becomes money politics where the rich and mighty can buy the outcome they want’ is destined to be rejected by the very majority of people, sooner or later. The sorrows of democracy are real, but it would be a hyperbole to call it the “end of democracy”. It is rather a necessity, a call for exploration of alternative forms of democracy to purge the shortcomings of the Western liberal democracy that are becoming perpetual source of these sorrows.

Trumpism and Oli-garchy may keep on raising their heads time and again, but it is the people who make history by their collective action, and who continue to carve new forms of democracy in accordance with their changing needs.

I submit a long view of human history is witness to this undeniable truth.