OR

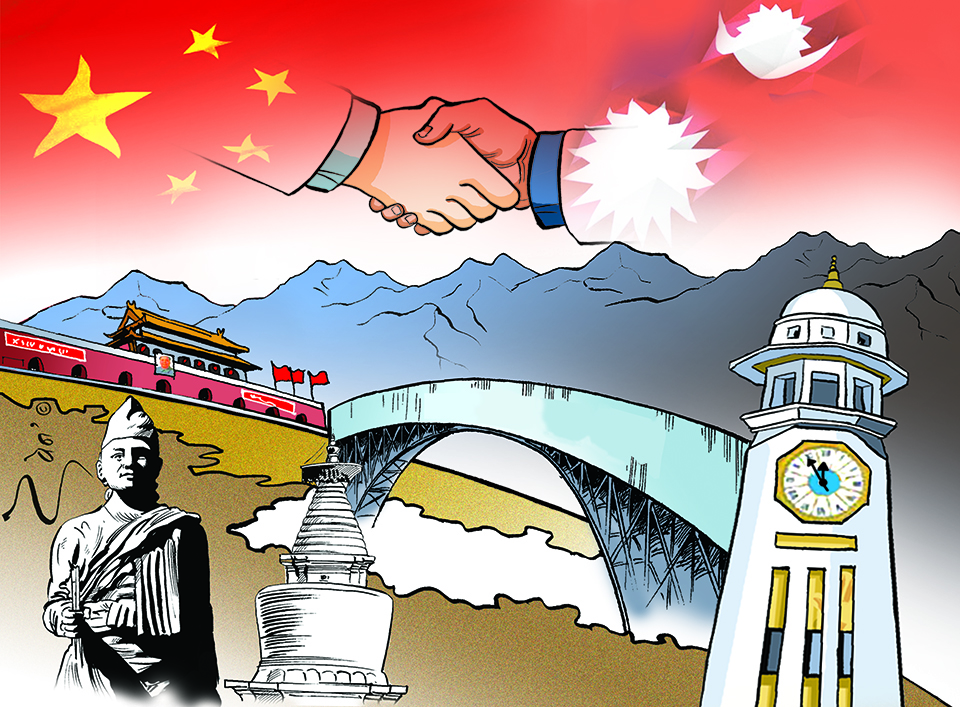

On the road to China

Published On: April 24, 2019 01:30 AM NPT By: Mahabir Paudyal | @mahabirpaudyal

Mahabir Paudyal

Mahabir Paudyal is an opinion writer at Republica with interest on history, domestic politics and international relations.mahabirpaudyal@gmail.com

More from Author

- Nepal is falling into a trap of India, China and the US

- Prime Minister Oli is pushing the country to precipice. Is there a way to stop him?

- How can you be so irresponsible about education?

- What is Nepali Congress thinking about China?

- Fellow Nepalis, fear the government, fear as much for the country

Metaphorically, maintaining Araniko Highway is also about maintaining tricky geopolitical gaze on Nepal, which seems to be intensifying now more than ever

I come from a village in Sindhupalchok district, wherefrom China border is only around 35 kilometers. Traders, businessmen and locals there are excited now because trade with China through Araniko Highway is resuming after four years of closure since 2015 earthquakes.

I feel strongly about this road because, in a way, it made me what I am today. Before this road to Kathmandu opened, Sindhupalchok and parts of Dolakha, Ramechhap and Kavre districts were virtually isolated from the capital. If people had to come to Kathmandu they would have to walk for three days along the trails. Those born in the 70s, like me, did not have to. We came to Kathmandu within four hours of bus ride.

Obviously, the importance of this highway lies in its economy but there is a great geopolitical story behind making of this road. Without knowing that story, we might not understand how important that road has been and will be for Nepal.

Highway with history

It was the 1960s. India was spreading its influence across South Asia. ‘Only Himalayas are our frontiers,’ was Jawahar Lal Nehru’s South Asia vision. Nepal had only begun to emerge from the era of absolute Indian control on politics and economy. Conflict between India and China was beginning to simmer. With Nepal, India was sore because it was beginning to assert itself in the international arena, regardless of what India thought.

China was to give message to India that Nepal was no longer its absolute backyard and that China could very much reach up to Indian land through Nepal. Nepal also found it as an opportunity to tell India: We have been India-locked for many years, now we want to reach out to China as well. Back in those days, as people of that era recall, Nepal was virtually locked on all sides. We had no road network with China. To go to Biratnagar and Mahendranagar from Kathmandu, one had to travel via India. East-West Highway was yet to be built. India was the only route to reach out to many parts of Nepal and beyond.

There are conflicting accounts on genesis of this highway. Available literature reflects on how paving it was fraught with challenges.

In Strategy for Survival Leo E Rose mentions that the highway was born not because King Mahendra wanted it but because China needed it more than Nepal. Road agreement was none of the agenda of King Mahendra’s 1961 China visit and it came “totally unexpected” on October 15, the last day of his visit to Peking,” writes Rose. “Dr Tulsi Giri signed the agreement for Nepal, possibly because Mahendra preferred to keep his own name off of what was certain to become highly controversial document to which New Delhi would raise serious objections.” Rose also claims that China pressured Nepal to sign this agreement by putting the condition that Nepal-China border agreement would be implemented only if “Nepal assented to road agreement.” Nonetheless, the agreement, he writes, provided the king a badly needed bargaining weapon in negotiation with India.

Expectedly, road agreement raised eyebrows in New Delhi. India reacted with rage, to pacify which Mahendra said ‘communism does not come by a taxi.’ India would not be satisfied with this explanation. In 1962, Nepal faces an ‘unofficial and undeclared economic blockade.’ Had not it been for 1962 war between India and China, Nepal would perhaps have to make major concessions on its foreign policy with India.

Bhuwan Lal Joshi in Democratic Innovations in Nepal (co-authored with Rose) does not subscribe to China’s need theory. Araniko Highway, he writes, is the result of “widespread resentment at the virtually total dependence upon India for Nepal’s general economic wellbeing.” Mahendra had a fear that India could use economic pressure to force political changes in Nepal. This is why, suggests Joshi, the king approached China for alternative route. But he does not give credit for it to only king. He describes the road as the outcome of “logical extension of Nepal’s efforts since 1947 to expand political and economic relations with countries other than India.”

Ramesh Nath Pandey, former foreign minister who worked closely with King Mahendra, argues along the same line. “The idea was to reduce dependency with India. No agreement between the two countries takes place when one of the countries wants it and other does not. The highway was of strategic importance for both the countries and both countries wanted it. The claim that Mahendra did not want it or only China wanted it is flawed,” he told me recently.

What came out?

Communism did not come to Nepal through Araniko Highway (communist party as we know today was actually formed in 1949 in India much before King Mahendra took over in 1960) but it could have brought some influence nonetheless. Writes Aditya Adhikari in The Bullet and Ballot Box: “The Chinese had been sending teams to build roads [Araniko Highway] in the hills of north-east Nepal since 1963. In 1967, the activities of the Chinese technicians working at the road-building sites began to alarm the Nepali government. The press reported that they were distributing Chinese revolutionary literature and Mao badges to construction laborers. They were also showing films promoting Chinese socialism. These ‘gullible’ Nepali workers, it was claimed, were forced to salute Mao’s portrait and chant slogans praising him before they received their wages.”

The Chinese officials who oversaw the project provide alternative version. In his account in You and Us: Stories of China and Nepal, Yang Gongsu, Chinese ambassador to Nepal in 1965 writes: “The Chinese experts ate, lived and worked together with Nepalese personnel and treated the Nepalese workers equally and taught them advanced techniques. As a rule, the wages of Nepali workers were paid by the Nepali officials but they often embezzled some of the funds.” Later through repeated consultations, writes Gongsu, the two sides agreed that Nepali supervisors would be paid once a section of the work was completed and Chinese side directly paid to Nepali workers according to the construction schedule.

He also speaks of geopolitical gaze. The highway project was opposed by India and America, he writes. They thought of it “as a strategic road for China to expand its presence in South Asia. Once something happened, the Chinese troops could directly enter India via this road from Tibet and even reach the Indian Ocean.”

Zeng Xuyong, Chinese ambassador to Nepal for 1998-2001, talks about Chinese Road Construction Battalion, the name given to the team of Chinese engineers and soldiers to “avoid foreign media whipping up hysteria” that “Chinese army has entered Nepal.” These soldiers, he mentions, “would wear dark grey plain clothes instead of military uniforms” to avoid suspicious eyes. What was China’s motive in opening the road? Tibet’s only channel to the outside world via Sikkim was completely closed after 1962 war (with India), Xuyong explains, and China needed to open a new channel to South Asia.

Those who lived through the 60s in the settlements along the road tell the story of how Nepali villagers came down in hundreds to dig road with spades, pushing the boulders off into the river, doing the backbreaking job of extracting quarries.

From trade to smuggling

The Araniko Highway became the trail of livelihood for many people in and outside of Sindhupalchok district. When the trade through this road started sometimes around 1980, people started go beyond the borders and bring goods from China. They bought Chinese cotton cloths and sold them in Kathmandu. It brought them considerable amount of money.

Around the same time, something else came through this highway which aroused fury of India, which resulted in blockade and regime change in Kathmandu. It was in August 1988. We were too young to understand politics, but trucks, it seemed in hundreds, loaded with (we knew not what then) entered via this road, often during the night, illuminating the whole villages with headlights, arousing curiosity among children. Elders whispered about the guns. Nepal was importing Chinese anti-aircraft guns.

After 1990’s political change, Khasa became the destination for the youths (including high school students), to go, bring cloths, jackets and shoes and sell them in either Bahrabise or Kathmandu. The temptation was high and many dropped out of schools for Khasa trade. Apparently, Khasa trade was so profitable that more people followed suit. You could simply go across the border (those with citizenship cards issued from Sindhupalchok district could go across the border without hassles), get a set of VCR or DVD player into Nepal and handing it over to tradesmen, would make at least Rs 300 at one go. A clever youth, it was said, would bring in at least three such sets a day.

Women fell for the temptation too. They wrapped up as many meters of cotton cloth around their waist underneath their saris, thinking that police on patrol would not go to the extent of asking them to take off sari and search. A meter of such cloth in Kathmandu would bring them the profit of at least Rs 10.

These cheap Chinese shoes, jackets and cloths replaced tattered clothes the poor wore up in the hills. Even the poor could afford to buy jackets and shoes. Many Nepalis could afford to wear good clothes and shoes after the Chinese goods flooded in Kathmandu, across the country and beyond.

Alongside, smuggling of animal skins, gold, pashmina wool, sandalwood and even people started to flourish slowly. Smugglers brought in gold and pashmina. From Nepali side trucks of sandalwood went to China. There were police posts (more than a dozen from Kathmandu to Kodari) but such trucks came and went unobstructed. This was facilitated by the nexus of smugglers, local politicians and police. Some of those smugglers have become politicians. Others influence elections in the district.

When these smugglers started bringing in Tibetans in various disguise, known then as bhote osarne, it became the source of consternation for the Chinese. Like in other smuggling racket, this was thriving in collusion with local political leaders. What started as a trail of geostrategic importance and the source of livelihood and trade started to emerge as a security concern. Nepali authority was pointed for misusing the road to undermine China’s security interests. One infamous incident relates to whisking George Fernandez (Indian defense minister from 1998-2004) to Khasa through Araniko Highway in 1993. When he returned to Kathmandu, he made noise about Tibet, irking China’s nerves and putting the government in Kathmandu in a difficult situation.

When the earthquakes ravaged the border towns, it ended the means of livelihood for the poor, the source of revenue for the country (Tatopani customs point was the biggest source of revenue, bringing as much as Rs five billion annually in taxes before it was closed down in 2015) and the smuggling spree.

Learn from history

Now that the road to China is reopening for trade, Nepali and Chinese authorities should ensure that it is used for legal trade of goods and avoid falling into smuggling trap—the disgrace that haunts the imagination of locals even today . Second challenge will be maintenance. There is perennial danger of landslides and floods on this road. Every monsoon, at least a few kilometers of road get enveloped in landslides or get swept off by raging Bhote Koshi.

Metaphorically, maintaining this road also implies maintaining tricky geopolitical gaze on Nepal, which seems to be intensifying day by day.

While expanding connectivity with China through rail and roadways has found renewed attention now because of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), India and America are visibly concerned about Nepal becoming a part of BRI. History has shown us costs, benefits, risks and challenges of maintaining connectivity with China. China and America are arch rivals of each other. One is worried about possibility of losing superpower status. The other is competing for that status. But foreign policy is also another name of unpredictability—today’s foes become friends tomorrow, today’s friends become foes tomorrow.

Nepal needs to think what works best for it. If the architects of Araniko Highway had listened to India, perhaps the road would never have been built. And I would not be writing about it today.

You May Like This

As they clash to conquer

Until Sino-US rivalry drags on, both China and America will try to have Nepal in their fold. How should Nepal... Read More...

Should Russians hug Chinese?

Putin and Xi are vying for global leadership in challenging the United States and the West, and both are channeling... Read More...

Road to war with China

It would be a huge mistake for America to adopt a cold-war posture toward China. Such a policy could ultimately... Read More...

Just In

- ADB Vice-President Yang pays courtesy call on PM Dahal

- PM Dahal, Chairman of CIDCA Zhaohui hold meeting

- MoFAGA transfers 8 under secretaries and 11 section officers (with list)

- PM Dahal arrives in Morang

- DDC pays Rs 480 million dues to farmers

- Police arrest seven Indian nationals with 1.5 kg gold and Rs 14.3 million cash

- Gold price increases by Rs 1,400 today

- Kathmandu continues to top the chart of world’s most polluted city

Leave A Comment